The New Mexico Campaign, 1861–1862

“When he had discharged that duty, he accompanied Sibley’s Brigade through New Mexico, sharing in the pains and vicissitudes of that campaign,”

— “Custodian of the Alamo,” San Antonio Light, February 23, 1887.

Gen. Henry Sibley organized a brigade to invade New Mexico.

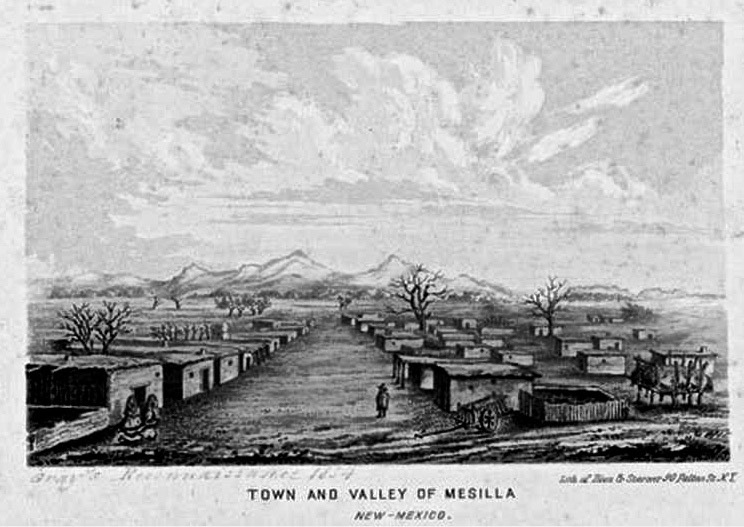

Lieutenant Colonel Baylor issued a proclamation forming the Confederate Territory of Arizona on August 1, 1861. A meeting of the pro-Confederate citizens of Mesilla in May 1861 commissioned George M. Frazer to form the Arizona Rangers. This company saw action at the battles at Valverde, Glorieta, Apache Canyon, and Peralta.1 The Arizona Rangers and the Arizona Guards were mustered into Confederate service for a term of 12-months.2

In July 1861, Henry H. Sibley, an officer who had resigned in May from the US Army at Fort Fillmore, New Mexico, received a commission as a brigadier general. Confederate President Jefferson Davis authorized General Sibley to raise a brigade of volunteers to invade New Mexico.3 Sibley returned to San Antonio and gathered volunteers.4

General Sibley’s brigade, consisting of the 4th, 5th, and 7th Texas Mounted Rifles, left San Antonio in October for El Paso on the Lower or Military road.5 The expedition intended to join with the men of the 2nd Regiment of Texas Mounted Rifles already in West Texas, expel Federal troops from the New Mexico Territory, and possibly annex New Mexico and the Mexican state of Chihuahua to the Confederacy. The ultimate goal was to secure an overland route from Texas to the Pacific coast.6

Stagecoaches continued to carry the mail. Rife later claimed that he accompanied Sibley’s command into New Mexico. Between October 1861 and May 1862, the 3,200-man brigade left Fort Bliss and traveled up the Rio Grande.7 It appears that Rife continued to work as a conductor on the mail stage during this period.8

The US Postmaster General discontinued mail service between El Paso and San Antonio on February 17, 1862, but George Giddings, the mail contractor, obtained a Confederate government contract to provide mail services between San Antonio and California.9 He realized that Federal troops and Indian troubles might prevent his men from going beyond El Paso10, but he kept the stages running between San Antonio and El Paso until August 1862.11

The Confederates invaded New Mexico Territory.

In December 1861, General Sibley arrived at Fort Bliss.12 Colonel John Baylor already had 630 men of the 2nd Regiment in seven cavalry companies and two artillery companies in the area. To avoid a probable conflict, General Sibley sent Baylor on a diplomatic mission to Mexico and gave Baylor’s command to Major Charles Pyron.13 General Sibley then claimed all of the New Mexico Territory for the Confederacy in a proclamation issued on December 20.14

In the spring of 1862, the Confederates began the invasion of New Mexico. Sibley’s brigade won the first major battle, the Battle of Valverde, on February 20.15 The Confederates then advanced up the Rio Grande valley. The Federal commander knew that the Texans were critically short of supplies, and on March 4, Federal troops removed 120 wagonloads of supplies from Albuquerque and sent them to Fort Union, northeast of Albuquerque. Retreating Federal troops destroyed the remaining supplies.16 The Confederate expeditionary force entered Albuquerque, and then on March 10, it occupied Santa Fé, the territorial capital.17

The Federal commander waited for reinforcements.18 The 1st Colorado Volunteers from Denver City, Colorado, reached Fort Union after traveling 400 miles in 14 days. Union troops and the Colorado volunteers left Fort Union and headed south along the Santa Fé Trail to Bernal Springs to meet the Texans. On March 26, 418 federal troops encountered and captured thirty-two Confederate scouts on the western slope of Glorieta Pass and clashed with 300 Confederates under Major Pyron in the Battle of Apache Canyon.19

The Federal troops retreated to Pigeon’s Ranch (a stage station on the Santa Fé Trail), and the Confederates camped at Johnson’s Ranch. Twelve inches of snow fell during the night.20 In the second battle at Glorieta Pass on March 28 both armies were advancing when they encountered each other in a thick pine and cedar forest. By the end of the day, the Texans had captured Pigeon’s Ranch.

The fight at Glorieta Pass ended in a draw, but during the fight, the Confederate supply wagon train at Johnson’s Ranch was destroyed.21 This loss was a decisive blow to the Texans.22 The Federal troops escaped to Kozlowski’s Ranch, and the Texans returned to Santa Fé.23

The Confederates retreated after the fight at Glorieta Pass.

On April 7, 1862, the Confederates returned to Albuquerque, where their remaining supplies were stored.24 A few days later, the Texans left Albuquerque heading south down the Rio Grande valley. They were attacked at Peralta on April 15 and then allowed to escape downriver.25

The Confederates fared no better in Arizona Territory than they did in northern New Mexico. Confederate troops penetrated to the west of Tucson but then abandoned the city before the arrival of the California Column.26 The California Column of 2,350 men was formed in San Francisco to guard the overland mail from Salt Lake City but was diverted to New Mexico when the Texans launched their invasion. The California Column reached Tucson on May 20 and Fort Thorn on July 4, 1862.27

The Confederates evacuated West Texas in 1862.

The remaining Confederate troops began to return from West Texas.28 In July and August, the half-starved and ragged men began arriving in San Antonio.29 The rearguard of the Confederate Army of New Mexico left Fort Fillmore and abandoned and burned Fort Bliss.30 Many families from Franklin (present-day El Paso) left for San Antonio with the Confederate troops, leaving the town almost deserted.31 After the last Confederate troops departed Fort Davis, the Apache Indians looted and burned the buildings. The last stagecoach from El Paso arrived in San Antonio on August 16, 1862. The coachmen found many of the mail stations along the route deserted or destroyed.32

Four days after the Confederates left Fort Davis, Union troops occupied Franklin. On August 20, men of the First California Volunteer Cavalry took possession of Fort Bliss; the stage line operated by George Giddings then suspended all service west of Fort Clark. Fort Clark was the western-most fort garrisoned by Confederate troops.33

The Texans of Sibley’s Battalion won every engagement; they captured Albuquerque and Santa Fé before retreating to El Paso.34 However, it was apparent that Sibley’s force was inadequate to hold northern New Mexico for the Confederacy. Sibley’s Battalion returned to San Antonio in small groups, and efforts were made to enroll recruits from different Texas counties.35 When Confederate Brigadier General J. Bankhead Magruder took command of Texas in November 1862, he used Sibley’s troops from the New Mexico expedition to recapture Galveston Island from the Federal army.36 In the spring of 1863, the various units of Sibley’s brigade were reorganized at East Bernard (a station on the Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio Railroad in Wharton County) for service outside Texas.37

West Texas remained a no man’s land until 1866.

Although Fort Clark was the western-most fort garrisoned by Confederate troops, the 1st California Cavalry patrolled as far as Fort Davis in August 1862.38 In December, a Federal patrol went east as far as the Horsehead Crossing of the Pecos to check on rumors that Henry Skillman and 6,000 troops were planning to attack Franklin and Fort Bliss.39 The patrol located no Confederates but found that Apaches were watching the road.40 Kiowa and Comanche raiders also continued their raids on Texans. During the Civil War, the line of established settlements moved east by about three counties as the women and children fled for safety.41

After the failure of the Confederate invasion of New Mexico, the Federal commander, US Lieutenant Colonel Edward Canby, asked to be reassigned to the Eastern front.42 Brigadier General James H. Carleton of the California Column assumed command of Federal troops in New Mexico. General Carleton launched a war against the Navajo, Kiowa, and Apache Indians that impoverished them and eventually drove them to reservations.43 When Carleton learned that the Confederates were preparing another invasion force, he promised a scorched earth campaign and ordered his commanders to prepare to destroy anything of value at San Elizario, Ysleta, Socorro, Fort Bliss, Franklin and Hart’s Mill, should the Confederates invade.44

-

Hall, The Confederate Army of New Mexico, 354 ↩︎

-

Hall, The Confederate Army of New Mexico, 21 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 17 ↩︎

-

Evans, Confederate Military History, Vol. XI: 54; Charles Merritt Barnes, Combats and Conquests of Immortal Heroes, (San Antonio: Guessaz & Ferlet Company, 1910), 143 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 38; Hall, The Confederate Army of New Mexico, 15 ↩︎

-

Austerman, “The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, CSA,” 97 ↩︎

-

The San Antonio Light, February 23, 1887 ↩︎

-

Thompson, From Desert to Bayou, 19, 23 ↩︎

-

Kathryn Smith McMilllen, “A descriptive bibliography on the San Antonio-San Diego Mail Line,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 59, No. 2, (October 1955), 206-14; Austerman, “The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, CSA,” 85 ↩︎

-

Wayne R. Austerman, “San Antonio-El Paso Mail,”” Handbook of Texas Online, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/eus01, accessed November 21, 2010 ↩︎

-

Austerman, “The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, CSA,” 95 ↩︎

-

George Wythe Baylor, Into the Far, Wild Country: True Tales of the Old Southwest, (El Paso: Texas Western Press, The University of Texas at El Paso, 1996), 186; Hall, The Confederate Army of New Mexico, 21 ↩︎

-

Hammons, A History of El Paso County, Texas, to 1900, 48; Hall, The Confederate Army of New Mexico, 23 ↩︎

-

Evans, Confederate Military History, Vol. XI, 55 ↩︎

-

Jay Wertz and Edwin C. Bearss, Smithsonian’s Great Battles and Battlefields of the Civil War, (New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc, 1997), 87; Jerry Thompson, ed., Civil War in the Southwest: Recollections of the Sibley Brigade, (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2001), 52 ↩︎

-

Wertz, Smithsonian’s Great Battles and Battlefields of the Civil War, 89 ↩︎

-

Hall, The Confederate Army of New Mexico, 31; Wertz, Smithsonian’s Great Battles and Battlefields of the Civil War, 89 ↩︎

-

Thompson, Civil War in the Southwest, xiv ↩︎

-

Wertz, Smithsonian’s Great Battles and Battlefields of the Civil War, 92 ↩︎

-

Thompson, Civil War in the Southwest, 85 ↩︎

-

Thompson, Civil War in the Southwest, xviii; Hall, The Confederate Army of New Mexico, 32 ↩︎

-

Hammons, A History of El Paso County, Texas, to 1900, 48 ↩︎

-

Wertz, Smithsonian’s Great Battles and Battlefields of the Civil War, 94 ↩︎

-

Hall, The Confederate Army of New Mexico, 33 ↩︎

-

Thompson, Civil War in the Southwest, xix, 119 ↩︎

-

Hall, The Confederate Army of New Mexico, 362 ↩︎

-

Wertz, Smithsonian’s Great Battles and Battlefields of the Civil War, 78-9 ↩︎

-

Hammons, A History of El Paso County, Texas, to 1900, 49 ↩︎

-

Miss Mattie Jackson, The Rising and Setting of the Lone Star Republic, (San Antonio: n.p., 1926), 107; Hall, The Confederate Army of New Mexico, 39; Thompson, Civil War in the Southwest, 125 ↩︎

-

Wertz, Smithsonian’s Great Battles and Battlefields of the Civil War, 98; Hall, The Confederate Army of New Mexico, 39; Hammons, A History of El Paso County, Texas, to 1900, 49 ↩︎

-

Austerman, “The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, CSA,” 94 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 46 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 48; Austerman, “The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, CSA,” 95-6 ↩︎

-

Austerman, “The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, CSA,” 93; Wharton, Texas Under Many Flags, 92; Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 41 ↩︎

-

Evans, Confederate Military History, Vol. XI: 55 ↩︎

-

Wharton, Texas Under Many Flags, 92 ↩︎

-

Thompson, From Desert to Bayou, 41; Evans, Confederate Military History, Vol. XI: 131 ↩︎

-

Austerman, “The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, CSA,” 95 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 49 ↩︎

-

Austerman, “The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, CSA,” 95 ↩︎

-

Stephen B. Oates, ed., Rip Ford’s Texas by John Salmon Ford, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1963), 349; Jackson, The Rising and Setting of the Lone Star Republic, 156 ↩︎

-

William L. Richter, The Army in Texas During Reconstruction: 1865-1870, (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 1987), 13 ↩︎

-

Wertz, Smithsonian’s Great Battles and Battlefields of the Civil War, 84 ↩︎

-

Jerry D. Thompson, “Drama the Desert: The Hunt for Henry Skillman in the Trans-Pecos, 1862-1864”, Password 37, (Fall 1992): 110 ↩︎