Vicksburg Campaign, 1862–1863

“…thence he passed to Mississippi and was wounded at Deer Creek near Vicksburg”

— “Custodian of the Alamo,” San Antonio Light, February 23, 1887.

Vicksburg was the key to control of the Mississippi River.

Control of the Mississippi River was of great strategic importance to the governments of both the United and the Confederate States.1 The side that controlled the Mississippi River was believed as likely to emerge as the war’s victor. Early on, the city of Vicksburg was identified as the key to control of the Mississippi. In January 1863, the US military began a campaign to wrest control of the city, and the river, from the Confederacy.2 The Mississippi Delta was a swamp except for the natural levees along the waterways. Numerous plantations were located on narrow strips of dry land bordering the levees3 The Delta was one of the most fertile agricultural areas of Mississippi. It was home to a large population of slaves and their white overseers.4

In the early months of the Civil War, Confederate authorities discouraged enlistment of troops in Texas, thinking that the war would be over quickly and that Texans would not be needed. Nevertheless, several companies formed and integrated into various southern regiments.5 Several units went to Mississippi and helped in the defense of Vicksburg.6

Rife was last observed in the upper Rio Grande Valley in July 1861; he stated that he accompanied the Confederate troops that invaded the Territory of New Mexico.7 These troops did not leave the region until August 1862.8 Rife also stated that he was wounded at Deer Creek in the Mississippi Delta, but he did not say when. Because we lack definitive information about how Rife came to be wounded at Deer Creek, we will describe the activities of military units that were active in the area between August 1862, when the Confederate campaign in New Mexico ended, and October 1863, when Rife returned to Texas.

Thomas Rife accompanied Waul’s Texas Legion to Mississippi in October 1862.

Waul’s Texas Legion was one of the Texas units that participated in the Vicksburg campaign. The Legion was formed in Brenham, Texas, on May 13, 1862, three months after Texas seceded from the Union. There were about 2,000 men on the rolls of Waul’s Legion when it was organized. While the known roster contains 1,350 names, the identities of about 650 men are as yet unknown.9

Waul’s Legion trained at Camp Waul, at Gay Hill in Washington County, a few miles north of Brenham. The unit camped there throughout the summer and left for Mississippi in August 1862.

When the Civil War began in 1861, mail service between Texas and points west was curtailed. The mail contractor was left with a fleet of wagons and mules that he disposed of as best he could. It appears that Rife purchased or received at least one wagon from George Giddings and returned to Brenham, where he had first lived when he came to Texas in 1842. In the summer of 1862, Rife hired his services as a freighter or wagon master at Camp Waul, where he received $11.00 for ten rolls of rope, and two mule harnesses on September 30.10

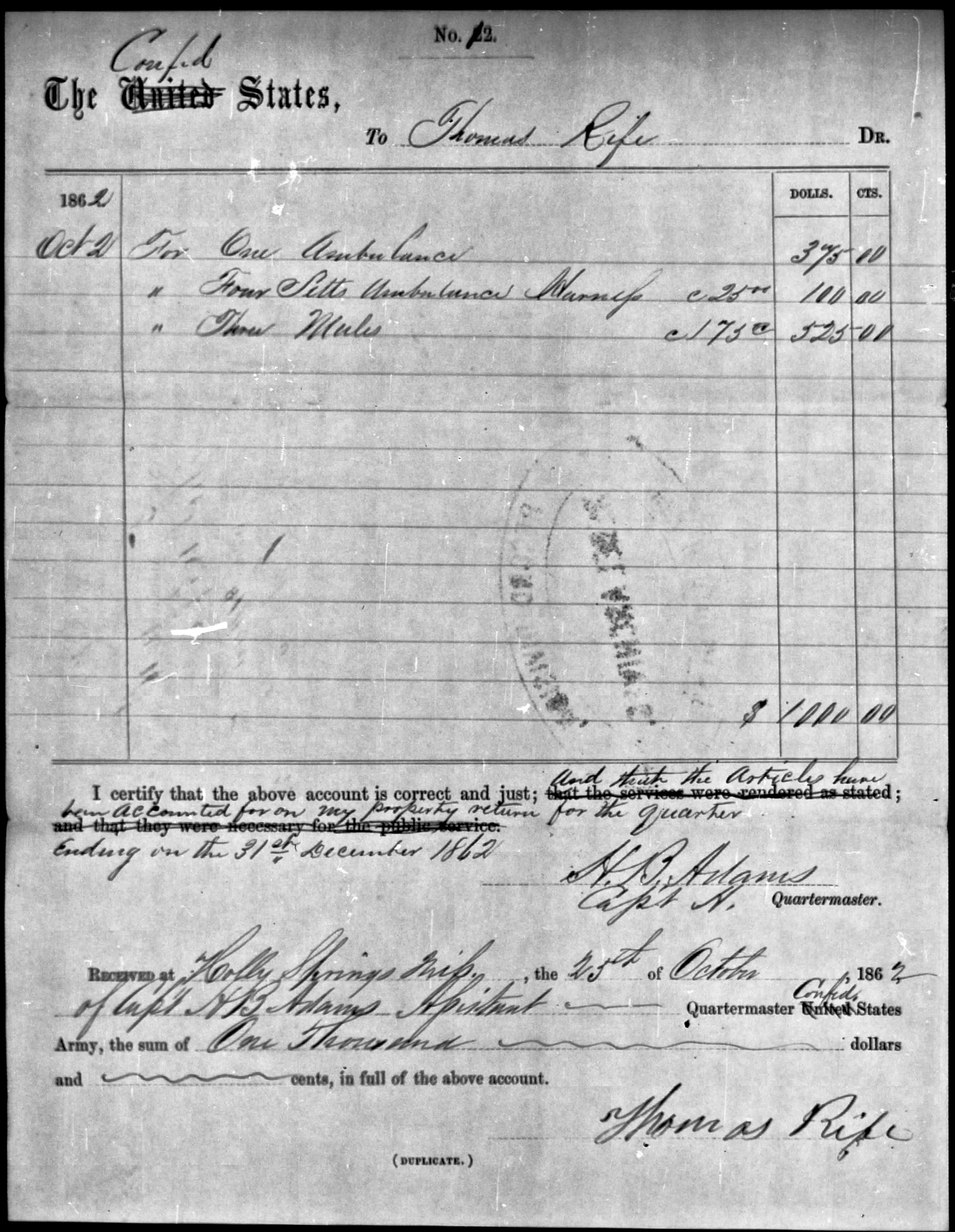

Rife accompanied the Legion to Holly Springs, Mississippi, probably driving a wagon. There, on October 2, he sold a wagon, four sets of harness, and three mules to the army for the sum of one thousand dollars.11

The Legion was dispatched to Grenada, Mississippi, arriving there in January 1863, where the Cavalry Battalion was detached and sent to Vicksburg. The infantry and artillery were sent to Fort Pemberton, in the Mississippi Delta, arriving there in February 1863.12 Rife may have accompanied the army to Fort Pemberton.

The Lake Providence Expedition, January to March 1863.

During 1863, Federal troops searched for a route to bypass the Confederate batteries at Port Hudson, Port Gibson, and Vicksburg that were blocking the passage of Federal shipping on the Mississippi River.13 Compared to the Confederate government, the Federal government seemed to have unlimited manpower and resources; General Ullyses S. Grant, the Federal commander of the Vicksburg campaign, adopted any suggestion that had even the slightest chance of silencing the Confederate guns at Vicksburg.14

One suggestion led to what was known as the Lake Providence Expedition. The plan was to make a canal through Lake Providence to the Ouachita River that, in turn, flowed to the Red River. The Red River emptied into the Mississippi River at Port Hudson, 100 miles south of Vicksburg.15 The canal would allow Grant’s army to move troops south of Vicksburg, where they could affect a landing on the east bank of the Mississippi River.

Beginning in January 1863, 1,000 Federal soldiers dug a canal upstream of Vicksburg on the Louisiana side to connect the Mississippi River with Lake Providence.16 When the canal was completed and opened, the bayous connecting Lake Providence to the Red River flooded.17 A steamboat then attempted, without success, to find a route between Lake Providence and the Red River in order to bypass Shreveport as well as Vicksburg.18 Trees growing in Baxter Bayou blocked the passage of Grant’s transports, and by the end of March, the attempt was abandoned.

The Yazoo Pass Expedition of February to April 1863 failed.

Several streams, running roughly parallel to the Mississippi River, drain the Mississippi Delta. These rivers and creeks all discharge into the Yazoo River. The Yazoo River then joins the Mississippi River just north of Vicksburg. Between January and April 1863, the US Navy and Army cooperated in various unsuccessful attempts to use these waterways to outflank Confederate defenses at Vicksburg.19

An effort was made to land an invasion force on the Mississippi side of the river north of Vicksburg in February 1863. The Mississippi River levee at Yazoo Pass was breeched to prepare for the Yazoo Pass Expedition.20 The breach flooded the entire region to a depth of 8½ feet.21 Federal gunboats entered Coldwater River, and on March 10, ten US Navy gunboats and troop transports reached a Confederate battery that blocked further passage. The battery, called Fort Pemberton, was still under construction.22 Fort Pemberton was built of cotton bales covered in sand and earth. A steamboat (the “Star of the West”) was sunk near the fort to block the river; Waul’s Texas Legion and three other infantry regiments were placed there to defend it.23

On March 11 and 13, Federal gunboats twice attacked Fort Pemberton but were driven off by the Confederates.24 The narrowness of the channel in front of the fort did not allow the Federal gunboats to turn sideways so their guns could not be used effectively25, and the US Army could not land troops because of the swampy terrain.

Fort Pemberton blocked the progress of the Federal gunboats for three weeks and prevented them from reaching Snyder’s Bluff26 where their troops could be landed. Reluctantly, General Grant abandoned the Yazoo Pass campaign and focused his attention elsewhere.27

The Steele’s Bayou Expedition of March 1863 also failed.

Beginning on March 14, 1863, another Union attempt was made to attack Vicksburg from the north. The Steele’s Bayou Expedition left the Mississippi River with the intention of traveling up the Yazoo River, Steele’s Bayou, Black Bayou, Deer Creek, Rolling Fork, and Big Sunflower River so federal troops could be landed upstream of Hayne’s and Snyder’s bluffs overlooking the Yazoo River and downstream of Fort Pemberton.

The Expedition began when five ironclads (referred to as “turtles”), four tugs, and two mortar boats left the Mississippi River at Young’s Point and traveled up the Yazoo River to Steele’s Bayou.28 At Deer Creek, they turned north toward the Little Sunflower River.

The Expedition traveled through a densely populated area with many plantations located on the natural levees that lined Deer Creek.29 The white inhabitants of the plantations fled at the approach of the ironclads, going east across the Tallahatchie River, while hundreds of Black slaves lined the banks to see the vast ships traveling the narrow waterways.30 Residents along the route hid their livestock and burned stores of cotton as the ironclads passed by, crashing into and destroying bridges and uprooting trees as they went. The ironclads used in the Steele’s Bayou Expedition were each 175 feet long and 51 feet wide and carried a crew of 251 men.31

By March 18, the ironclads were within seven miles of Rolling Fork on the Little Sunflower River.32 Willow trees growing in Deer Creek slowed the gunboats leading the flotilla to a crawl.

Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Ferguson’s brigade of Confederates were camped at Fall’s Plantation when they learned of the approaching Federal flotilla. Captain George Barnes started overland with the cavalry for Rolling Fork, and the infantry and artillery embarked on a steamboat to be transported there. On March 19 at 4 pm, Ferguson’s Confederate troops arrived at the junction of Rolling Fork and Little Sunflower River only to find the road flooded.33

The Federal gunboats became stalled on Deer Creek.

Upon arriving at the junction of Rolling Fork and Deer Creek, Colonel Ferguson impressed slaves to cut trees to block the channel in front of the Woodfork plantation. White overseers from nearby plantations led the gangs of slaves to cut trees growing on the banks of the flooded waterway.34 After traversing most of Deer Creek, the gunboats found that willow trees growing in and along the streambed near the L. C. Watson plantation blocked their passage forward.35 Rear Admiral David D. Porter, the commander of the US Navy’s Mississippi River Squadron, directed three hundred sailors to leave the gunboats to prevent Confederates from approaching the stalled ships.36 These men mounted a battery on a nearby Indian mound.37

That same day, Colonel Ferguson sent the Arkansas regiment and his artillery to attack Federal patrols guarding the gunboats. The Confederates dislodged the battery on the Indian mound but were driven off by fire from the gunboats.38 Admiral Porter, aware of his danger, paid a slave from a nearby plantation to carry a message through Confederate lines to General Sherman asking for re-enforcements.39

The next day, March 21, 1863, Ferguson’s Confederate cavalry, led by Captain Barnes, moved down the creek and began felling trees across the stream, effectively trapping the gunboats. The Federal gunboats tried to escape by drifting backward, bouncing from bank to bank since they could not steer backward and could not turn around in the narrow waterway.40 Admiral Porter prepared to abandon and scuttle the ships if necessary. However, the Confederates were slow in mounting their attack and instead spent the time sniping at Union work parties trying to clear the channel.41 They were unaware that Federal reinforcements were rapidly approaching from the south.

Union infantry rescued the trapped gunboats on Deer Creek.

At 3 pm, the 8th Missouri regiment of US infantry (Giles Smith’s) reached Dr. Moore’s plantation, drove the snipers away and rescued the trapped boats.42 General Smith rounded up all Black males that he encountered to keep the Confederates from using them to cut more trees to block the waterway.43 By midnight, work parties from the trapped boats had cleared the channel, and the boats backed away with Smith’s men moving along both sides of the bank to keep the Confederate snipers at bay.44

Meanwhile, General William T. Sherman led the remaining US infantry on a march by candlelight through the night of March 21.45 Sherman’s force reached the ironclads just as the Confederates mounted an assault.46 As a result, the Confederates were driven back before they could mount a decisive attack on the gunboats. The Confederates withdrew to Rolling Fork, and the Union gunboats continued to back down Deer Creek, reaching the Mississippi River a week later.47

No Texas units participated in the action at Deer Creek. During this campaign, Waul’s Texas Legion and the 2nd Texas Regiment remained at Fort Pemberton. If Rife was wounded at Deer Creek as he said he was, he might have been engaged as a partisan operating outside of military control or as a volunteer with the home guard or one of the Mississippi units that participated in the campaign. He had good reason to be in the area. His sister, Mary Jane, and brother-in-law, Lawrence Wade, owned a 350-acre plantation, called Wade Lawn on the Mississippi side of the river only a dozen or so miles from Deer Creek and Rolling Fork. The plantation backed up to a swamp that drained into Steele’s Bayou.48

Waul’s Legion was captured at Vicksburg.

In April 1863, Waul’s infantry and artillery were moved six miles from Fort Pemberton to Point Leflore at the junction of three rivers (Tallahatchie, Yalobusha, and Yazoo) two miles northwest of the town of Greenwood, Mississippi.49 In May 1863, two companies of Waul’s Legion infantry were sent to Yazoo City, the location of a large Confederate navy yard. They were captured in July and sent to a prison camp in Indiana. The rest of Waul’s Legion retreated to Vicksburg; they were forced to surrender in July along with the rest of Confederate General Pemberton’s besieged army. The men of Waul’s Legion were paroled in August and September 1863 and reorganized again at Houston in October and November.50

A year after the surrender of Vicksburg, the Confederate prisoners were exchanged and allowed to return to active service. After crops were harvested in the late summer of 1864, and news of the prisoner exchange circulated among the paroled soldiers, soldiers began to straggle back to their regiments. However, most units never returned to their full strength. Disease and enemy fire had killed up to one-third of the men involved in the Vicksburg campaign. Some men joined other units, and a few never reported back. Many had joined local militia units to support Confederate troops near their homes. If captured, they falsely identified their regiment to avoid being interned for breaking parole.51

Confederate soldiers were cared for in hospitals.

If Thomas Rife was wounded at Deer Creek in 1863 while in military service, he would have been sent to a regimental or field hospital nearby. Confederate army military hospitals kept extensive records of wounded and sick soldiers.52 However, most Confederate military hospital records were lost. By the time the collection, purchase, and compilation of Confederate records began in 1878, many documents were already destroyed. A few were taken home and retained by the officer in charge of the hospital. This was the exception rather than the rule53, however, and few such records are known to exist today.

-

Douglas B. Ball, Financial Failure and Confederate Defeat, (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 93; William L. Shea and Terrence J. Winschel, Vicksburg Is the Key: The Struggle for the Mississippi River, (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2003), 12, 39 ↩︎

-

Earl Schenck Miers, The Web of Victory: Grant at Vicksburg, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1955),118; Shea, Vicksburg Is the Key, 60 ↩︎

-

Edwin Cole Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg: Vicksburg is the Key, (Dayton, OH: Morningside House, 1985), Vol. 1: 479 ↩︎

-

Edwin Cole Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg: Vicksburg is the Key, Vol. 1: 479 ↩︎

-

Wharton, Texas Under Many Flags, 90; Alex Sweet and J. A. Knox, On a Mexican Mustang through Texas from the Gulf to the Rio Grande, (Hartford, Conn: SS Scranton & Co, 1883), 590 ↩︎

-

Evans, Confederate Military History, Vol. XI: 65, 131 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Light, February 23, 1887 ↩︎

-

Austerman, “The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, CSA,” 95 ↩︎

-

Robert Hasskarl and Captain Leif R. Hasskarl, Waul’s Texas Legion: 1862-1865, (Ada, OK: self published, 1985), 119 ↩︎

-

Thomas Rife, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, 1861-1865, M346, RG 109, National Archives and Records Administration, Roll 865 ↩︎

-

Thomas Rife, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, 1861-1865, M346, RG 109, NARA, Roll 865 ↩︎

-

Hasskarl, Waul’s Texas Legion, 116 ↩︎

-

Wertz, Smithsonian’s Great Battles and Battlefields of the Civil War, 314-5, 365 ↩︎

-

Shea, Vicksburg Is the Key, 60-3 ↩︎

-

Miers, The Web of Victory, 107 ↩︎

-

Miers, The Web of Victory, 93 ↩︎

-

Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg, Vol. 1: 478; Miers, The Web of Victory, 92 ↩︎

-

Swanson, Atlas of the Civil War Month by Month, 58 ↩︎

-

Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg, Vol. 1: 482; Wertz, Smithsonian’s Great Battles and Battlefields of the Civil War, 364-8 ↩︎

-

Swanson, Atlas of the Civil War Month by Month, 60; Shea and Winschel, Vicksburg Is the Key, 69 ↩︎

-

Miers, The Web of Victory, 110; Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg, Vol. 1: 485 ↩︎

-

Miers, The Web of Victory, 111; Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg, Vol. 1: 506 ↩︎

-

Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg, Vol. 1: 507; Miers, The Web of Victory, 114 ↩︎

-

Ballard, Vicksburg, 189; Miers, The Web of Victory, 111-6 ↩︎

-

Shea, Vicksburg Is the Key, 70-1 ↩︎

-

Wertz, Smithsonian’s Great Battles and Battlefields of the Civil War, 365; Hasskarl, Waul’s Texas Legion, 19 ↩︎

-

Ballard, Vicksburg, 189 ↩︎

-

Miers, The Web of Victory, 119 ↩︎

-

Shea, Vicksburg Is the Key, 72 ↩︎

-

Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg, Vol. 1: 554-5 ↩︎

-

Shea, Vicksburg Is the Key, 96 ↩︎

-

Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg, Vol. 1: 556 ↩︎

-

Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg, Vol. 1: 561 ↩︎

-

Miers, The Web of Victory, 122 ↩︎

-

Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg, Vol. 1: 555 ↩︎

-

Shea, Vicksburg Is the Key, 74 ↩︎

-

Ballard, Vicksburg, 186 ↩︎

-

Ballard, Vicksburg, 186 ↩︎

-

Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg, Vol. 1: 559; Ballard, Vicksburg, 186 ↩︎

-

Ballard, Vicksburg, 187 ↩︎

-

Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg, Vol. 1: 566 ↩︎

-

Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg, Vol. 1: 570 ↩︎

-

Ballard, Vicksburg, 187 ↩︎

-

Shea, Vicksburg Is the Key, 74; Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg, Vol. 1: 570 ↩︎

-

Ballard, Vicksburg, 188 ↩︎

-

Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg, Vol. 1: 577 ↩︎

-

Shea, Vicksburg Is the Key, 75; Wertz, Smithsonian’s Great Battles and Battlefields of the Civil War, 367 ↩︎

-

John Tourette, Plantation Map of Carroll Parish, LA, www.usgwarchives.org/maps/louisiana/parishmap/carrolllatourette1848.jpg: accessed Nov 12, 2012 ↩︎

-

Hasskarl, Waul’s Texas Legion, 20 ↩︎

-

Hasskarl, Waul’s Texas Legion, 56 ↩︎

-

Richard, The Defense of Vicksburg, 263 ↩︎

-

Carol C. Green, Chimborazo: The Confederacy’s Largest Hospital, (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2004), 26 ↩︎

-

Glenna R. Schroeder-Lein, Confederate Hospitals on the Move: Samuel H Stout and the Army of Tennessee, (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1994), 163, 179 ↩︎