Custodian of Fort Bliss, 1861

“…but when the civil war broke out, Rife was serving the south, and was at the surrender of Fort Bliss and, by command of General McGuffen, took charge of the garrison, and held it for the confederates”

— “Custodian of the Alamo,” San Antonio Light, February 23, 1887.

After Abraham Lincoln was elected, the South seceded.

Less than a month after the national elections of November 1860, citizens of San Antonio held a public meeting at 10 o’clock on Saturday morning, December 1, in Military Plaza. The assembly drew up a petition calling for a secession convention.1

On January 28, 1861, the Secession Convention met in Austin and approved an ordinance of secession to be submitted to the State’s voters for their approval.2 The voters approved the ordinance a month later; 46,129 voted for secession, and 14,697 voted against it.3 Texas seceded from the Union despite the opposition of Governor Houston and other leading men.4

The Secession Convention passed Ordinance Number One relating to the removal of Federal troops from Texas; transports and vessels necessary to facilitate the removal of troops from the State could not be seized or interfered with by citizens or State authorities.5 The Convention appointed a 15-man Committee of Public Safety to oversee the removal of Federal troops and to manage frontier defense. The committee, in turn, sent a delegation to the 8th Military District in San Antonio to make arrangements for the removal of Federal troops and the transfer of Federal property to the State.6

Expecting resistance from the US Army, Ben McCullough and John Baylor raised a company of 250 volunteers to occupy the rooftops of buildings used by the US Army in San Antonio.7 After ten days of negotiation with Commissioners from the Committee of Public Safety, US General David M. Twiggs, commander of the 8th US Military District, ordered the 8th Infantry to abandon Fort Davis and all 19 US army posts in Texas.8 General Twiggs agreed that all US troops would leave Texas and turn over surplus supplies and equipment to State officials.9

Texas affiliated itself with the Confederate States on March 16, 1861.10 The Governor and Secretary of State refused to swear an oath to the Confederate Constitution; the Legislature declared their offices to be vacant.11 Two days later, District Judge Devine led the citizens of San Antonio as they took the Oath of Allegiance to the Confederacy.12 Delegates to the Succession Convention then passed an ordinance to ratify the Constitution of the Confederate States of America.13

All Federal troops left the State or were captured.

By mid-April, all the military posts in West Texas had been evacuated by Federal troops.14 After the attack on Fort Sumter in South Carolina, Confederate Colonel Earl Van Dorn was instructed “to intercept and prevent the movement of the US troops from the State of Texas” because hostilities had begun.15 Texas military commanders also called for the surrender of Federal troops who had reached the Gulf Coast. The Federal troops garrisoned at Fort McIntosh in Laredo, first went to Fort Brown in Brownsville and then to the port at Indianola, expecting to board ships for the North. On April 25, 1861, after some confusion, they surrendered to Texas officers.16

In the meantime, Federal troops abandoned Fort Bliss and Fort Quitman and marched to Fort Davis.17 The combined battalion proceeded to Fort Stockton and then marched towards the Gulf Coast to be transported to the North as per the agreement between General Twiggs and the State commissioners.18

On May 6, the combined garrisons of the frontier forts, all under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Isaac V.D. Reeves,[^19] arrived at San Lucas Spring, 15 miles west of San Antonio, and camped on Allen’s Hill.19 The 270 Federal troops were surrounded by an overwhelming force of 1,370 Confederate, state and volunteer troops led by Colonel Earl Van Dorn.20 The Confederates threatened to attack; on May 9, Colonel Reeve surrendered to the Confederates. The Union troops were permitted to march to San Antonio, where they were held as prisoners of war.21 The Union officers were paroled. Some of the enlisted men were kept at San Pedro Park near San Antonio for 22 months as prisoners of war before being exchanged.22

Commissioners were appointed to safeguard government property.

The Texas Committee of Public Safety appointed Confederate commissioners to take custody of and to safeguard all Union property in the State.23 The committee appointed James Magoffin as commissioner for Forts Bliss and Quitman. Before Federal troops left Forts Bliss and Quitman, James and his son, Samuel Magoffin, accepted custody of the supplies and equipment at the posts.24 Colonel Reeve then abandoned the fort.25 On April 4, 1861, Samuel Magoffin and his brother-in-law, Gabriel Valdez, received the Federal property at Fort Quitman from First Lieutenant Zenas Bliss.26 The contents of both forts were inventoried for transfer to the State.27

On April 25, 1861, a volunteer company of Confederate partisans from San Antonio (members of a secret society called the Knights of the Golden Circle) occupied Fort Davis.28 Noah Smithwick wrote that in April when he passed by Fort Quitman on his way to California, four men were guarding the fort. They were waiting for the arrival of John Baylor’s Texas troops.29 Fort Stockton, in a partially dismantled state, was also occupied by State troops.30 California-bound emigrants seeking firewood damaged both Fort Stockton and the relay stations belonging to the Overland Mail. They were ignorant of the fact that the ground was “full of mesquite grubs” (roots) that could be used for firewood.31

Thomas Rife and other men took custody of Fort Bliss.

By order of Confederate Commissioner-General James Magoffin, a prominent El Paso merchant and political figure, Thomas Rife and a few other men, including S. W. Merchant, took custody of Fort Bliss.32 During this time, Rife was employed by Giddings’ stagecoach line, perhaps as a station agent near El Paso. Thirty-two years later, Tom Rife, in telling a story, claimed to have been at Fort Bliss on St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, 1861.33

In a letter to the Texas Governor in May 1861, Josiah F. Crosby urged the Governor to raise a company or more of militia to protect the property at Fort Bliss. He recommended that Captain H. Clay Cook be authorized to raise this company. James Magoffin agreed to take the responsibility of rationing and arming the company.34 In a report, Colonel Earl Van Dorn, the senior Confederate officer in Texas, stated that he “has mustered into service a company of foot artillery, composed of old soldiers, under a good officer, and put them at Fort Bliss with instructions to throw up a small field-work, and to defend it with the six pieces of artillery now there.” 35 Rife must have passed his responsibility as the fort’s custodian to this force because soon afterward, he was seen driving the mail coach.36

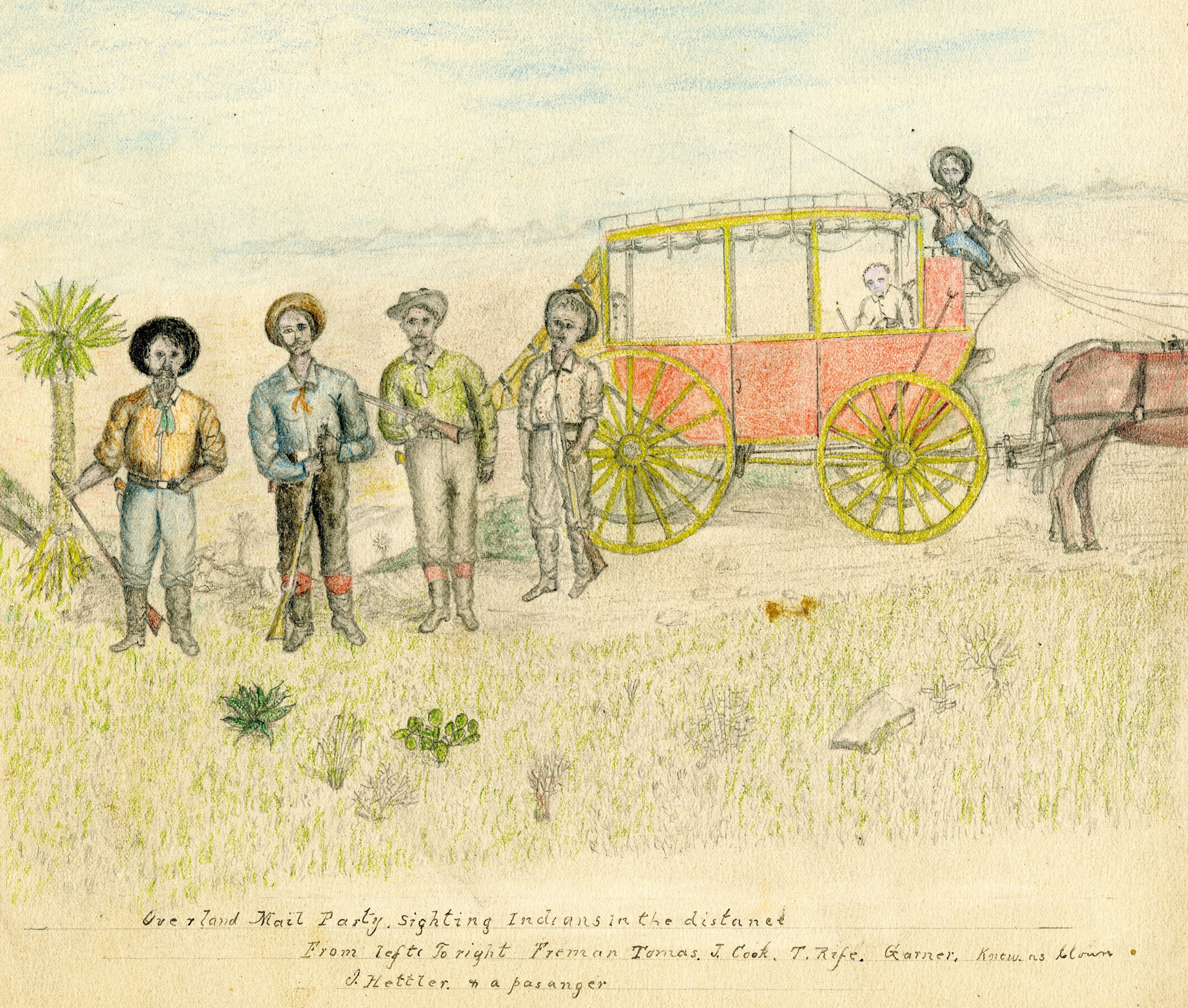

The mail service continued to run on a semi-weekly basis37, and mail stations continued to be manned.38 On July 10, 1861, Rife led a mail party near El Muerto (Dead Man’s Hole) west of Van Horn’s Well. The mail coach was headed to El Paso, Texas.39 Three days later, Rife and his party were reported 30 miles west of San Elizario and headed in the direction of San Antonio.40 The final mail coach from San Diego arrived in Mesilla on July 20.41

Confederate troops occupied the abandoned forts.

On May 7, 1861, Lt. Colonel John R. Baylor arrived in San Antonio to organize a regiment of mounted volunteers for frontier defense.42 This regiment, the 2nd Regiment, Texas Mounted Rifles, was detailed to occupy the vacated US military forts from Fort Brown to Fort Bliss along the Rio Grande frontier.43 The following month, units of Baylor’s regiment began to move west from San Antonio to occupy the forts along the San Antonio-El Paso Road. Colonel Baylor arrived at Fort Bliss in the stagecoach on July 13,44, and by the end of the month, Confederate troops occupied most of the abandoned military posts in West Texas.

Fort Bliss, located three miles east of Franklin (or Coontz’) ranch, was the western-most military post in Texas. Franklin’s ranch was on the east bank of the Rio Grande River opposite El Paso del Norte, Mexico.45 In 1858, Franklin had a population of about 300 persons, three-fourths of whom were Mexicans. Irrigation ditches provided water for vineyards, fruit trees, wheat, corn, and vegetable gardens. There was a saloon and a US post office (both in the same room), an outdoor market and a ferry that crossed the river to El Paso del Norte. The town was described as picturesque with ash and cottonwood trees lining the river.46

However, Baylor had not traveled to Franklin merely to garrison Fort Bliss; he had a broader mission.47 On July 23, 1861, Baylor left his base at Fort Bliss and invaded New Mexico Territory, still under the control of the United States Army. Companies A and E, the San Elizario Spy Company, and part of Teel’s Artillery Company left Fort Bliss and traveled upstream for 44 miles to attack the US forces at Fort Fillmore, New Mexico. The Confederate troops bypassed the fort and occupied Mesilla, a large town just north of Fort Fillmore.48 The US Army garrison of Fort Fillmore marshaled in front of the town but then retreated back to the fort after a brief skirmish. On July 27, the Union garrison of Fort Fillmore abandoned the fort and began to march to Fort Stanton, 140 miles to the northeast. Baylor’s command, with some civilians from Mesilla, pursued and overtook the US troops.49 The Federal soldiers surrendered at San Augustine Springs without a fight. This surrender was the first victory for the Confederates in the New Mexico campaign.50

-

Citizens of Bexar County to convene the legislature, Records of the Legislature: Constitutional Conventions, Secession Convention 1861, Memorials and Petitions (March 1861), Archives and Information Services-Texas State Library and Archives Commission ↩︎

-

Records of the Legislature: Constitutional Conventions, Secession Convention 1861 (March 1861), ARIS-TSLAC ↩︎

-

Jerry Thompson, Editor, Texas and New Mexico on the Eve of the Civil War: The Mansfield and Johnston Inspections, 1859-1861, (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2001), 181; Mark Swanson, Atlas of the Civil War Month by Month: Major Battles and Troop Movements, (Athens & London: The University of Georgia Press, 2004), 10 ↩︎

-

Clarence R. Wharton, Texas Under Many Flags, (Chicago and New York: The American Historical Society, Inc., 1930), 85; Noah Smithwick, The Evolution of a State or Recollections of Old Texas Days, (Austin: Gammel Books Co., 1900), 331 ↩︎

-

Records of the Legislature: Constitutional Conventions, Secession Convention 1861 (March 1861), ARIS-TSLAC ↩︎

-

J. W. Magoffin to EC (April 28, 1861), Records of Edward Clark, Texas Office of the Governor, ARIS-TSLAC ↩︎

-

Wharton, Texas Under Many Flags, 89; Jerry Thompson, From Desert to Bayou: The Civil War Journal and Sketches of Morgan Wolfe Merrick, (El Paso: The University of Texas at El Paso, 1991), 6 ↩︎

-

David P. Smith, Frontier Defense in Texas: 1861-1865, (Denton, TX: North Texas State University, 1987), 55-7; Mrs. S. J. Wright, San Antonio de Bexar: An Epitome of Early Texas History, (Austin: Morgan Printing, 1916), 89 ↩︎

-

Jerry Thompson, ed., Texas and New Mexico on the Eve of the Civil War, 182 ↩︎

-

Records of the Legislature: Constitutional Conventions, Secession Convention 1861 (March 1861), ARIS-TSLAC ↩︎

-

Wharton, Texas Under Many Flags, 87 ↩︎

-

Wright, San Antonio de Bexar, 105 ↩︎

-

Records of the Legislature: Constitutional Conventions, Secession Convention 1961, ARIS-TSLAC ↩︎

-

Clayton W. Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier: Fort Stockton and the Trans-Pecos, 1861-1895, (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 1982), 8; The Daily Ledger and Texan (San Antonio), April 2, 1861 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 8-9; Clement A Evans, ed., Confederate Military History, (Thomas Yoseloff, New York, 1962,) Vol. XI: 46; United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate Armies, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office), Series 1-Volume 1: 627 ↩︎

-

Thompson, Texas and New Mexico on the Eve of the Civil War, 183; Mark Swanson, Atlas of the Civil War Month by Month, 14 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 7 ↩︎

-

Thompson, From Desert to Bayou, 105, note 31; Wayne R. Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules: The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, 1851-1881, (College Station, TX: Texas A & M University Press, 1985), 164 [^19] United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies, Series 1-Volume 1: 567-70 ↩︎

-

Thompson, From Desert to Bayou, 105 ↩︎

-

Swanson, Atlas of the Civil War Month by Month, 14 ↩︎

-

United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies, Series 1-Volume 1, 573-4; United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies, Series 1-Volume 1: 567-70; United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies, Series 1-Volume 1: 572-3 ↩︎

-

Frank S. Faulkner, Jr., Historic Photos of San Antonio, (Nashville and Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing Company, 2007), 15; Thompson, Texas and New Mexico on the Eve of the Civil War, 183; Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 8 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 43; Thompson, From Desert to Bayou, 11; Wright, San Antonio de Bexar, 105 ↩︎

-

Marsha Lea Daggett, ed., Pecos County History, (Fort Stockton, TX: Pecos County Historical Commission, 1973-1983), 45 ↩︎

-

Thompson, Texas and New Mexico on the Eve of the Civil War, 183 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 8 ↩︎

-

Smith, Frontier Defense in Texas, 61; J. W. Magoffin to EC (April 28, 1861), Records of Edward Clark, Texas Office of the Governor. ARIS-TSLAC. ↩︎

-

Thompson, From Desert to Bayou, 8, 10 ↩︎

-

Smithwick, The Evolution of a State, 340 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 12 ↩︎

-

Smithwick, The Evolution of a State, 254 ↩︎

-

The San Antonio Light, February 23, 1887; John W. Hunter, “Fighting with Sibley in New Mexico,” Frontier Times, Vol. 3, Number 12, (September 1926): 9 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Daily Light, March 25, 1893 ↩︎

-

J.F. Crosby to (Gov.) (May 9, 1861), Records of Edward Clark, Texas Office of the Governor, ARIS-TSLAC ↩︎

-

United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies, Series 1-Volume 1, 573-4 ↩︎

-

Thompson, From Desert to Bayou, 19, 23 ↩︎

-

Nancy Lee Hammons, A History of El Paso County, Texas, to 1900, (El Paso: The University of Texas at El Paso, 1983), 46 ↩︎

-

Smithwick, The Evolution of a State, 254 ↩︎

-

Thompson, From Desert to Bayou, 19 ↩︎

-

Thompson, From Desert to Bayou, 23 ↩︎

-

Wayne R Austerman, “The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, CSA,” West Texas Historical Association Year Book, Vol. 58 (1980): 86 ↩︎

-

The Daily Ledger and Texan, May 8,1861 ↩︎

-

Smith, Frontier Defense in Texas, 106; United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies, Series 1-Volume 1: 573-4 ↩︎

-

Martin Hardwick Hall, The Confederate Army of New Mexico, (Austin: Presidial Press, 1978), 19 ↩︎

-

Thompson, Texas and New Mexico on the Eve of the Civil War, 15; Thompson, From Desert to Bayou, 24 ↩︎

-

Hammons, A History of El Paso County, Texas, to 1900, 43; Albert D Richardson, Beyond the Mississippi: From the Great River to the Great Ocean, 1857-1867, (American Publishing Company, Hartford, Conn 1867), 238 ↩︎

-

Hammons, A History of El Paso County, Texas, to 1900, 46; Wayne R Austerman, “The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, CSA,” 86 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 18 ↩︎

-

Hall, The Confederate Army of New Mexico, 21 ↩︎

-

Hammons, A History of El Paso County, Texas, to 1900, 46; Smithwick, The Evolution of a State, ↩︎