Topographic Engineers, 1848

“Some time he was engaged with Colonel Joseph E. Johnson and Lieutenant Bryan in hunting out and opening the El Paso roads.”

— “Custodian of the Alamo,” San Antonio Light, February 23, 1887.

In 1848, the US Army built roads linking San Antonio and California.

When the United States and Mexico signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the US was given sovereignty over what became the States of New Mexico, Arizona, and California. At that time, the only road linking the United States with the newly acquired Territory of New Mexico was the Santa Fé Trail.1

Until 1849, there was no direct route between San Antonio and the upper Rio Grande valley. A trail between San Antonio and Santa Fé existed during the Spanish period, but it was suitable only for pack animals. This road was dangerous and rarely used. Before the Mexican War, the only usable road between San Antonio and El Paso del Norte ran through Saltillo, Hidalgo del Parral, and Chihuahua City in order to avoid the Despoblado area of West Texas and northern Mexico.2

Not only was the Despoblado an unexplored desert3 without a single Mexican or Anglo resident,4 it was also the traditional territory of Mescalero Apache Indians.5 In addition to the menace from Apaches, Comanche trails from what is now Oklahoma, and north-central Texas ran through the Despoblado to Mexico.6 The presence of Comanche raiders prevented settlement in the Despoblado.7

The 11th Article of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo guaranteed that the US would prevent Indians from raiding into Mexico8 although neither the Spanish nor the Mexicans had ever been able to accomplish this. The treaty required the US to build military posts to block the movement of Indians across the border. The border itself had to be surveyed and marked. The merchants of San Antonio also hoped to secure some share of the lucrative trade with northern Mexico that passed through St. Louis and Santa Fé.9 For these and other reasons,10 the US Secretary of War sent Brevet Major General William Worth to Texas. He had instructions to examine the country on the north bank of the Rio Grande from San Antonio to Santa Fé11 and to construct a road to connect San Antonio with New Mexico and California.12

Upper and Lower Military Roads were built to El Paso del Norte.

The first effort after the Mexican War to open a road to the New Mexico Territory was made by Colonel John C. Hays and Ranger Captain Samuel Highsmith, leading a thirty-five-man escort of Texas Rangers. This expedition left San Antonio on August 27, 1848, and returned on December 20. While unsuccessful in finding a route to El Paso, they did happen upon an attractive route to Presidio.13

Two months after the Hays expedition returned, General Worth and the citizens of San Antonio sent out a second exploring expedition. Major Robert Neighbors and John S. Ford were charged with finding a route for the movement of troops as well as for commercial purposes.14 This expedition mapped out what became known as the Upper El Paso-San Antonio Road.15

On February 12, 1849, another group of 16 men led by US Army engineers Captain William Whiting and Lieutenant William Smith left San Antonio to reconnoiter the entire region between San Antonio and west Texas. Their instructions were to find a suitable road for military and commercial purposes and to select suitable sites for military posts.16 This group followed the Upper Road between Fredericksburg and the upper Rio Grande Valley but returned along the more southern route that was followed by the Hays Expedition.17 On the return trip to San Antonio, they mapped out the southern or Lower El Paso-San Antonio Road.18

The Lower Military Road was chosen as the preferred route.

Both John Ford and Captain Whiting recommended the southern route (the Lower road) because they found too few waterholes along the northern route (the Upper road) to support the large number of animals needed to haul freight wagons.19 The Army engineers agreed that the Lower road was the preferred route.

In June 1849, General Worth dispatched a much larger military party with civilian laborers20 to test and improve the lower route located by the Whiting-Smith Expedition.21 Major Jefferson Van Horne commanded six companies of the 3rd Regiment of US Infantry and their support personnel. The men of Company E, 3rd Regiment, 3rd US Infantry, and a small group of civilian employees constructed the road to US Government specifications. It was better and broader than most roads of the day.22

The fatigue party of soldiers and civilian workers cleared the road of boulders and widened it for use by wagons. “Two weeks were spent at Devil’s River cutting down the bank before wagons could get down into the channel,” stated John L. Mann in the February 20, 1898, edition of the Dallas Morning News.23 They also cleared and enlarged the waterholes located by Captain Whiting.24

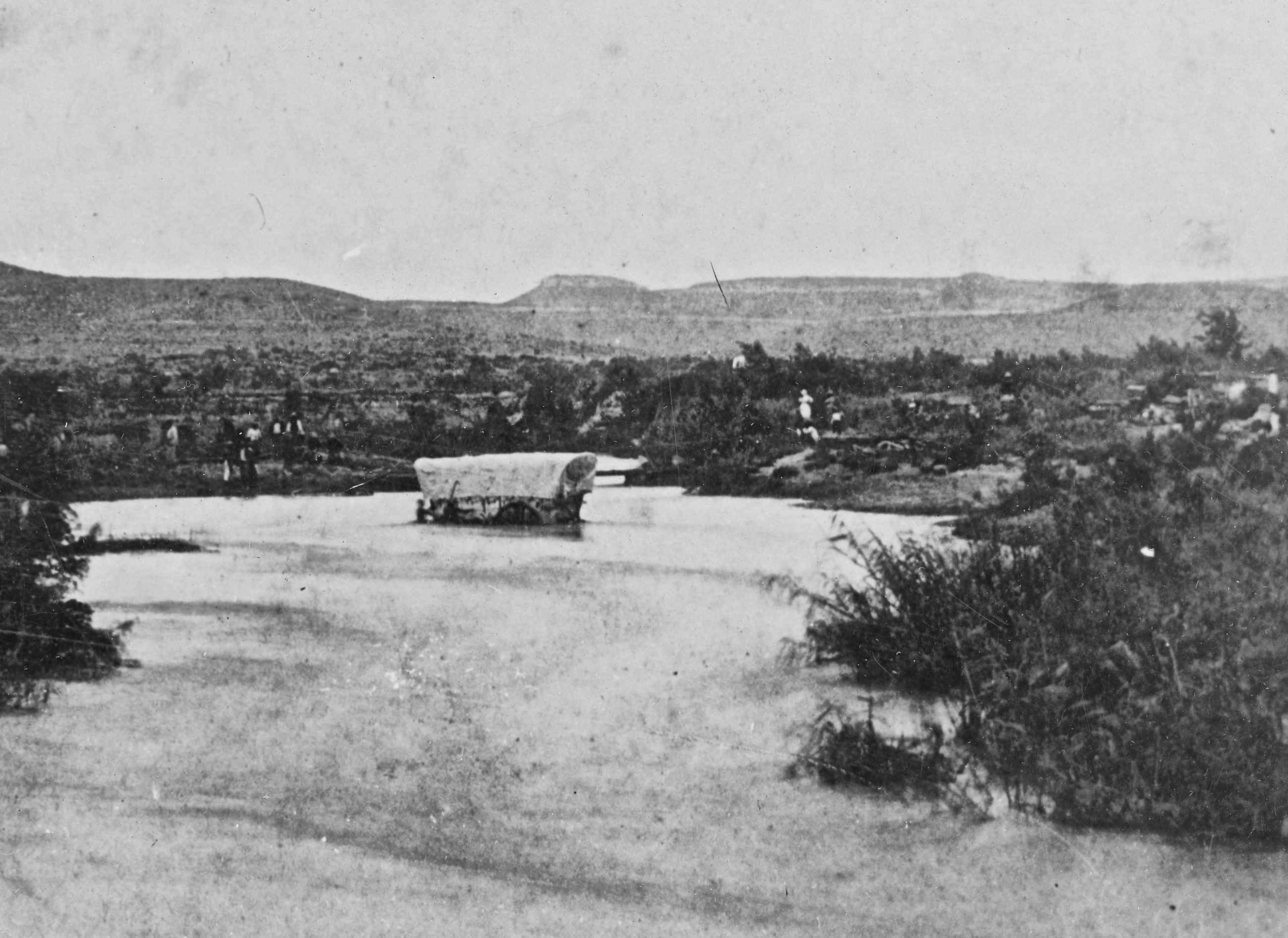

Over 1,000 oxen, a large number of mules and several emigrant trains, each with large herds of cattle, followed the military’s train of 275 wagons.25 The wagon train also included individuals seeking their fortune in the west.26 Captain Jack Hays had been appointed Indian Sub-Agent on the Gila River also accompanied the train.27 The massive wagon trains of civilians trailed along behind, waiting for the army to open each stretch of road before proceeding.28

The train left San Antonio in late May of 1849 and traveled from León Springs through the settlements of Castroville, Quihi, and Vandenburg. It reached the Leona River (present-day Uvalde) on June 3 and San Felipe Springs (present-day Del Rio) on June 8, 1849.) There, the large train was broken up into smaller segments preparatory to entering the desert where both water and forage were scarce.29

Instead of following the obvious route up the Rio Grande, the road left the river at Devil’s River to its headwaters at Beaver Lake before turning northwest across tableland to Howard’s Well and the Pecos River. This detour was necessitated by a plateau cut by deep canyons west of the Pecos River and north of the Rio Grande. The canyons run in a general southeasterly direction and empty into either the Pecos River or the Rio Grande. A traveler heading west or east would have to ascend and descend these ridges making the route too difficult to cross with loaded wagons.30

After crossing the Pecos, the road turned west and reached Comanche Springs, present-day Fort Stockton. Beyond Comanche Spring, the train crossed the timber-covered Davis Mountains and then another stretch of desert. The train went from waterhole to waterhole until it crossed the Quitman Mountains and came to the Rio Grande, 100 miles south of El Paso del Norte. The train then followed the Rio Grande upstream to San Elizario, Socorro, and Ysleta and reached an American-owned ranch across the river from El Paso del Norte31 on September 8, 1849.32

This 600-mile road became the main route to the west from San Antonio33 until 1883 when the southern transcontinental railroad (now the Southern Pacific RR) opened for service.

The route of the Lower Military road was determined by the availability of water.

The route of the road was chosen primarily because of the availability of water and grass along the route.34 The terrain and the location of river crossings ultimately determined the exact route chosen for these wagon roads. The road led from one water source to the next; sometimes, it was a river, sometimes a spring. As new sources of water were discovered, the route of the road changed to shorten the distance between waterholes. When the overland mail ran on the Lower Road, stage stations were placed where water was found and where forage could be stored, at intervals of about 25 or 30 miles apart.

The availability of forage for mules and horses was of paramount importance. Between San Antonio and the Pecos River, the grass vegetation was either prairie grassland (tall grass) or desert grassland (mesquite grass), both of which were suitable for horses and mules.35 Between the Pecos River and the Davis Mountains, desert vegetation (creosote bush) dominated, and both water and forage were scarce. While both were available in the Davis Mountains, to the west another long stretch of the desert had to be crossed until the road met the Rio Grande River at Quitman Pass.

There were many rivers to cross, and finding a suitable crossing was imperative. The Pecos was particularly tricky as it was a rapidly flowing stream for three hundred miles upstream of the Rio Grande. It was 65’ to 100’ wide, 7’ to 10’ deep, and usually the color of red mud.36 The river generally ran between steep banks, making it difficult for animals to get close enough to the river to drink and quicksand was common.37 The crossings at Live Oak Creek and Horsehead were two of the few suitable, and both were old Indian raiding trails to Mexico.38 The El Paso-San Antonio Road utilized these same river crossings.

Americans settled east of the Rio Grande near El Paso del Norte.

The first settlement encountered after reaching the Rio Grande was San Elizario (San Elceario before 1852), the most populous town in the Trans-Pecos region and the eastern-most town in the upper Rio Grande valley.39 Between San Elizario and El Paso, Del Norte Mexicans and Suma and Piro Indian farmers inhabited the river valley.40 The American settlement was just the three houses comprising Coonz or Coontz Ranch. On September 8, 1849, the US Army built the “Post Opposite El Paso” on Coontz’ Ranch and operated it with six companies of US infantry. Two companies of US troops were also quartered in the town of San Elizario.41

In 1848 migrants to the California gold rush were already traveling through San Antonio along the Lower Road. They did this rather than traveling through Mexico or over the Isthmus of Panama. The older route through Parras and northern Mexico to Mazatlán was still in use and would continue to be used for many years. It was much shorter than the overland route to California and avoided the Arizona desert. The route through Mazatlán also avoided contact with the Apache Indians, who, after 1849, no longer considered Americans their allies.42 Routes through Parras rather than El Paso had an additional advantage; Comanche raiders rarely ventured that far south.43

A San Antonio newspaper reported on August 4, 1849, that upwards of 4,000 emigrants with 1,200 to 1,500 wagons were camped on the Rio Grande near Coontz’ ranch on their way to California.44

The Upper Presidio Road went to Eagle Pass.

During the summer of 1849, Colonel Joseph E. Johnston and Lieutenant Bryan engaged Tom Rife to hunt out and open roads in west Texas.45 He may have accompanied the Topographic Engineers on the road-building expedition to Coontz’ Ranch from June until October 1849, but there is no evidence of that. However, he did escort Army surveyors laying out the Upper Presidio Road between San Antonio and Eagle Pass.46 This road began at Uvalde on the Lower San Antonio-El Paso Road and followed the route of Woll’s Road to Eagle Pass on the Rio Grande.47 Rife was among the first Anglo men to live in the vicinity of Uvalde and may have served as a guide or a guard for the surveying party. The following year Rife once again joined a ranging company.

-

A. B. Bender, “Opening Routes Across West Texas, 1848-1850”, Southwestern Historical Quarterly 37, No. 2, (October 1933), 117 ↩︎

-

Walter Prescott Webb, The Great Plains, (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1936), 86; S. C. Gwynne, Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History, (New York: Scribner, 2011), 61 ↩︎

-

Bender, “Opening Routes Across West Texas, 1848-1850”, 123 ↩︎

-

Donald E. Everett, San Antonio Legacy, (San Antonio: Trinity University Press, 1979), 14 ↩︎

-

Webb, The Great Plains, 51; Raht, The Romance of Davis Mountains, 88 ↩︎

-

Raht, The Romance of Davis Mountains map ↩︎

-

Gwynne, Empire of the Summer Moon, 61 ↩︎

-

Raht, The Romance of Davis Mountains, 91 ↩︎

-

Greer, Colonel Jack Hays, 216-7 ↩︎

-

Jack C. Scannell, “A survey of the Stagecoach Mail in the Trans-Pecos, 1850-1861”, West Texas Historical Association Year Book 47, (1971), 115 ↩︎

-

Bender, “Opening Routes Across West Texas, 1848-1850”, 119 ↩︎

-

Raht, The Romance of Davis Mountains, 85 ↩︎

-

Bender, “Opening Routes Across West Texas, 1848-1850”, 118-9 ↩︎

-

Bender, “Opening Routes Across West Texas, 1848-1850”, 119 ↩︎

-

The Texas Democrat (Austin), June 23, 1849; (486) The Corpus Christi Star, June 30, 1849; The Texas Democrat (Austin), August 4, 1849; Bender, “Opening Routes Across West Texas, 1848-1850”, 125 ↩︎

-

Bender, “Opening Routes Across West Texas, 1848-1850”, 121 ↩︎

-

Bender, “Opening Routes Across West Texas, 1848-1850”, 122 ↩︎

-

Bender, “Opening Routes Across West Texas, 1848-1850”, 123 ↩︎

-

Jack C. Scannell, “A survey of the Stagecoach Mail in the Trans-Pecos, 1850-1861”, 116 ↩︎

-

Jerry Thompson, editor, Texas and New Mexico on the Eve of the Civil War: The Mansfield and Johnston Inspections, 1859-1861, (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2001), 8 ↩︎

-

Charles G. Downing and Roy L. Swift, “Howard, Richard Austin”, Handbook of Texas Online, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fho90, accessed October 07, 2012; Democratic Telegraph and Texas Register (Houston), June 21, 1849; Williams, Never Again, Texas: 1848-1861, 34 ↩︎

-

Dallas Morning News, October 3, 1937 ↩︎

-

“Texas Pioneers,” Dallas Morning News, February, 1898 ↩︎

-

Bender, “Opening Routes Across West Texas, 1848-1850”, 123 ↩︎

-

Bender, “Opening Routes Across West Texas, 1848-1850”, 123 ↩︎

-

Williams, Never Again, Texas: 1848-1861, 33 ↩︎

-

Greer, Colonel Jack Hays, 228 ↩︎

-

Patrick Dearen. Devils River: Treacherous Twin to the Pecos, 1535-1900, (Ft. Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 2011), 31 ↩︎

-

Williams, Never Again, Texas: 1848-1861, 34 ↩︎

-

Greer, Colonel Jack Hays, 221 ↩︎

-

Williams, Never Again, Texas: 1848-1861, 36 ↩︎

-

Bender, “Opening Routes Across West Texas, 1848-1850”, 124 ↩︎

-

Anonymous, Texas Almanac, 1859, 139-140 ↩︎

-

Jack Lowery, “Guarding the Westward Trail”, Texas Highways Magazine 39, No. 9, (September 1992), 46 ↩︎

-

Webb, The Great Plains, 30-1; Williams, Never Again, Texas: 1848-1861, 15 ↩︎

-

Raht, The Romance of Davis Mountains, 23 ↩︎

-

Raht, The Romance of Davis Mountains, 86 ↩︎

-

Raht, The Romance of Davis Mountains, 86 ↩︎

-

Raht, The Romance of Davis Mountains, 121, 132,143 ↩︎

-

Raht, The Romance of Davis Mountains, 121 ↩︎

-

Rick Henricks and W. H. Timmons, San Elizario: Spanish Presidio to Texas County Seat, (El Paso: Texas Western Press, The University of Texas at El Paso, 1998), 71 ↩︎

-

Greer, Colonel Jack Hays, 236, 244 ↩︎

-

Williams, Never Again, Texas: 1848-1861, 7 ↩︎

-

The Texas Democrat (Austin), August 4, 1849; Nancy Lee Hammons, A History of El Paso County, Texas, to 1900, (El Paso: The University of Texas at El Paso, 1983), 34 ↩︎

-

The San Antonio Light, February 23, 1887 ↩︎

-

Galveston Daily News, December 28, 1894; San Antonio Daily Light, December 27, 1894; The San Antonio Daily Express, December 28, 1894 ↩︎

-

C. D. and H. Castellaw, eds., “Fort Inge, Uvalde County, Texas”, Branches and Acorns 8, Southwest Texas Genealogical Society, No. 4, (June 1993), 29-30 ↩︎