Wallace’s Ranger Company, 1850–1851

“Two years later he joined Big Foot Wallace’s frontier company and one year afterwards he was mustered out…”

— “Custodian of the Alamo,” San Antonio Light, February 23, 1887.

After the Mexican War, the US Army again took Texas rangers into Federal service.

When the United States Congress annexed the Republic of Texas, the expectation was that the US Army would provide for the defense of the frontier and that Texas troops would be called into State service only at the request and expense of Federal authorities.1 By 1849, it became apparent that the US Army by itself was unable to prevent Indian depredations in Texas. Thomas Rife participated in an experiment that, for a year and a half, beginning in 1850, tested whether a mixture of US and State troops could keep Indians from raiding into the settled areas of Texas.

In the 1850s, the line of settlement in Texas advanced 10 miles per year to the west.2 The Texas frontier was 500 miles long and 125 miles deep by the end of the decade. To prevent Indians from raiding along this frontier and into the settled parts of Texas and Mexico, the US Army built a line of outposts or forts west of the line of settlement. In 1849, the line of seven posts extended from the Red River in the north to the Nueces River in the south. An additional six posts were located along the Rio Grande River.3 By 1854, six military posts north of Fort Inge were abandoned, and eight new posts were constructed further west.

After 1856, the US Army operated two defensive lines on the frontier.4 Infantry manned the outer line, and mounted troops manned the inner line.5 In theory, the infantry formed a picket line to warn the mounted troops of the approach of Indian raiding parties.6 The mounted troops then blocked the Indian’s advance into the settlements. The mounted troops consisted of dragoons, Mounted Rifles, and, after 1856, cavalry.7

It was the strategy of the US military to force the Indians to “retire beyond the line of Posts.”8 Only in this way, the government reasoned, could the two people, Anglos and Mexicans on the one hand and free Indians on the other, hope to live in peace. Most Indians also believed this. The Comanche chiefs, in their negotiations with Sam Houston, repeatedly asked for a fixed border between themselves and the settlers.9 However, the steady westward movement of the line of settlement and the Comanche tradition of stealing horses from south Texas and Mexico made this solution impossible.

Fort Inge was built to guard the frontier.

Fort Lincoln (two miles from D’Hanis) and Fort Inge (thirty miles to the west) were essential forts in the first chain of military posts built after the Mexican War.10 On March 13, 1849, Company I commanded by Captain Seth Eastman of the 1st US Infantry, established a camp called Camp Leona (or Post on the Leona) on the east bank of Leona River, four miles north of Woll’s Crossing.11 The site is one mile south of the present town of Uvalde between a 140-foot volcanic plug called Mt. Inge and the Leona River.12 On March 24, Company D, 1st infantry, arrived, and in December 1849, the encampment on the Leona was renamed, Fort Inge.13

Fort Inge was typical of the one-company US Army bases of the period.14 The soldiers built the fort themselves.15 Most buildings were of jacal (post and mud) construction and were considered to be temporary.16 A hospital, added later, and a stone wall, built during the Civil War, were the only permanent structures at the fort.17

In 1849, when US Army Major General George M. Brooke assumed command of the 8th Military Department (the Department of Texas), it had a total roster of 1,500 infantry, artillery, and dragoons.18 Nevertheless, Comanche raiders continued to cross into Mexico in large numbers. In 1849, Ben McCulloch, who traveled through northern Mexico on his way to California, reported that “The Indians are breaking up the frontier settlements all along the route we came, being worse than they were ever known.”19 Indians were raiding into Texas as well, and in May 1849, the Army took steps to reinforce the Texas line.20

General Brooke called for Texas volunteers in 1849.

Realizing that his regular soldiers could not prevent Indian raids into Texas by themselves, the US Army general commanding the Department of Texas determined to employ State troops to assist them.21 On August 11, 1849, General Brooke, in Orders No. 53, notified his command that “In consequence of the repeated and continued depredations of the Indians, the commanding General has determined to make a requisition on his Excellency Governor George T. Wood of Texas for three mounted companies of Rangers.22

On that same day, General Brooke wrote to the Governor of Texas, saying that he had been authorized by the President of the US to request that the Governor authorize three companies of 78 rangers each for Federal Service.23 The ranging area of the three companies would be in the vicinity of Goliad, Corpus Christi, Bexar County, and other places that the Indians had recently raided.24

In Order No. 57, written on August 19, 1849, George Deas, Assistant Adjunct to General Brooke, wrote that “The Commanding General is thus calling for the services of volunteers, in preference to making a requisition for an additional number of regular troops, pays a just tribute to the favorable consideration in which the Texas Ranger is held, for the performance of the harassing and arduous duties of a frontier soldier. The General feels confident that the well-earned fame of the hardy sons of Texas will, in their coming sphere of action, be well sustained, by a vigorous prosecution of their campaign, and hopes, that long ere their term of service shall have expired, we shall no longer be annoyed by the presence, within our settlements, of the audacious and marauding savage.”25

The Governor responded quickly to General Brooke’s request and commissioned John S. Ford, J.B. McCown, and R.E. Sutton to organize the three companies.26 At the call of the three captains, prospective rangers each arrived at the appointed rendezvous27 with their horse, saddle, saddle blanket, bridle, halter, and lariat28 as well as clothing and blankets.29 The following day, the captains selected 78 men to form a company as specified in General Brooks’ Order.30 After each company was organized, the company elected a Captain, a 1st Lieutenant, and a 2nd Lieutenant.31 The Governor had previously informed the Army when and where the troops would be available;32 on the appointed day, an officer of the Army mustered the company into Federal Service using instructions provided by the War Department.33

After being mustered in, the company left the rendezvous site and traveled to their designated Army post. The captain reported to the commanding officer for instructions.34 The Army ordinance officer issued the men arms consisting of a percussion rifle35 and a pistol with its holster.36 The men were also issued ammunition and camp and garrison equipment.37

The companies organized by John Ford and J. B. McCown were ready to muster in on August 23, 1849.38 Each company consisted of one captain, one 1st lieutenant, one 2nd lieutenant, four sergeants, four corporals, two buglers, two farriers and blacksmiths, and 64 privates. After being mustered into service, the company proceeded to Corpus Christi to report to the Commanding General for special instructions.39 John S.(Rip) Ford’s company was assigned to the area around Corpus Christi.40

Rife enlisted in Wallace’s ranging company in 1850.

On March 6, 1850, General Brooke called on Texas Governor P.H. Bell for a fourth similar company to be placed in Federal Service. General Brooke candidly stated to Governor Bell that, “there is, at present, no money in the Treasury for the payment of volunteers, but from assurances which I have received from the Honorable Secretary of War, I feel confident that an early appropriation to that effect, will be made by Congress.”41

A few days later, William “Big Foot” Wallace was commissioned to raise a company of rangers in Bexar County for an enlistment of six months.42 On March 23, 1850, Captain William Steele of the 2nd Dragoons mustered the company into Federal service at 2 pm at the Federal Arsenal in Austin.43 Captain Steele was required to “inspect closely each man and horse, and to reject both, or either, unless they appear sufficiently strong and capable of bearing the arduous duties and fatigues of an Indian campaign.” As was the custom, each man furnished his horse, saddle, saddle blanket, bridle, halter, and lariat, and the government supplied a percussion rifle, pistol, and ammunition.44 Afterward, the company reported to the Commanding General in San Antonio for instructions.45

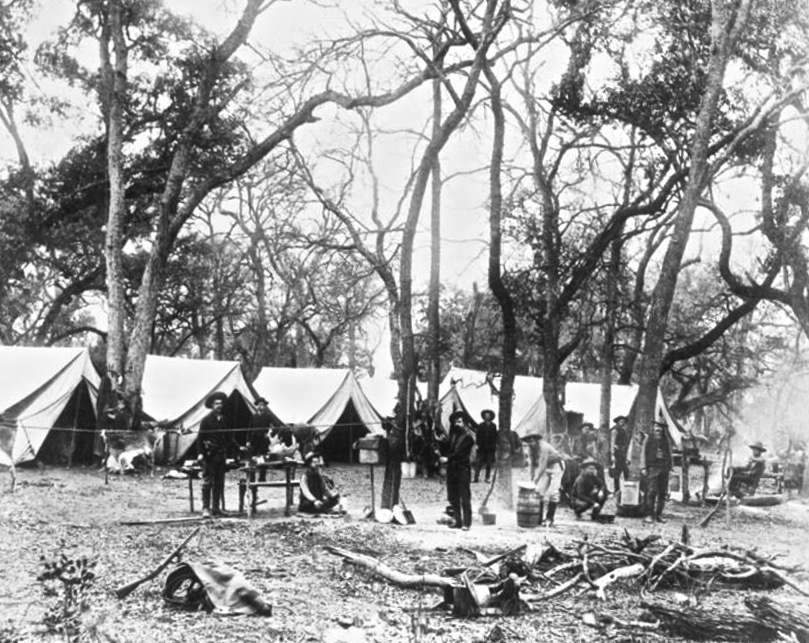

This unit was paired with Colonel Hardee’s US Infantry stationed at Fort Inge.46 Wallace’s ranging company and Capt. William Hardee’s Company C, Second Dragoons, both used Camp Leona as their base camp. The rangers camped on the west side of the river47, and the soldiers occupied two crude barracks on the east side of the river at Fort Inge. Both the US soldiers and the rangers were mounted riflemen. Regular soldiers at Fort Inge from 1849 to 1852 were Dragoons, who were trained to fight on horseback or foot. Mounted infantry (who fought on foot) occupied the fort from 1852 to 1855. Between 1856 and 1861, the soldiers at Fort Inge were cavalry. Mounted infantry mounted on horses when these were available but sometimes used mules because horses were scarce in Texas. Rangers were always well mounted, entered the service with their horses, and could fight either mounted or on foot.

The area of operation of Wallace’s company was between Seco Creek and the Guadalupe River from Bandera Pass to the coast.48 This area was sometimes called the Nueces Strip.49 As a result of the addition of Wallace’s company, Ford’s company took a new position at San Antonio Viejo in the lower Rio Grande valley to protect the vicinity of the Ringgold Barracks in Rio Grande City and Fort McIntosh at Laredo. Capt. McGown’s company was moved to an area between Ft. Inge on the Leona River and Fort Duncan on the Rio Grande at Eagle Pass.50

A joint military campaign against Indians was launched in 1850. By June 4, 1850, General Brooke felt that he was ready to move against the numerous and bold Comanche and Lipan Indian raiders in south Texas. He issued order No. 27 on June 4 to all available Dragoon and Mounted Infantry at Forts McIntosh, Inge, Merrill, and Lincoln together with the ranging companies of Ford, Grumbles, McCown, and Wallace. The troops were ordered to prepare to take the field, ”at an early date” against the Indians. The campaign would last at least two months or “until the country is cleared of those hostile Indians.” A detachment of Dragoons was left to protect Fort Inge on the Leona River and Fort Lincoln on Seco Creek, both of which were exposed to attacks by Lipan Apache Indians.51 It appears that the entire garrisons of Forts McIntosh and Merrill were to take the field in this scout, leaving as few as four men to guard the forts.52

Major Babbitt, Chief Assistant Quartermaster, was directed to establish depots of forage at Fort Merrill, where the Corpus Christi-San Antonio Road crossed the Nueces River. Major Longstreet, Chief of the Subsistence Department, was directed to place supplies for the troops at Forts Merrill, Inge, and Lincoln53 Colonel Hardee of the 2nd Dragoons was assigned to lead the scout.54 Wallace and his company were told to proceed towards Corpus Christi.55

Rife participated in the fight at Black Hills.

Nineteen men were on this scout, including Edward Westfall56 and Tom Rife.57 On July 18, 1850, the rangers were returning northwest to their camp on the Leona River. As Wallace and his company examined the country from the Nueces to Espantosa Lake, they encountered hostile Comanche Indians at Black Hills, a summit sixteen miles from Cotulla in present-day La Salle County.58 In the ensuing fight, three rangers were wounded, and seven Indians killed.

As the rangers approached a waterhole on Todos Santos Creek, about eighty mounted Comanche Indians, camped at the waterhole, came out to meet them. The rangers dismounted and prepared for an assault. The Indians stopped just out of gunshot range. Their leader repeatedly charged close to the rangers, encouraging his men to follow. On the third charge, Wallace ordered three of his men to shoot the Indian leader’s horse while Wallace, with a large caliber rifle, shot the man through both hips. The rest of the Indians then charged forward to rescue their wounded leader. Some of the rangers mounted their horses and fought the Indians at close quarters, using their pistols.

With their leader wounded, the Indians retreated to the waterhole with the rangers following close behind them. The Indians continued to retreat up the creek and left the rangers in possession of the waterhole. The Indians had been camped for a week or more, making lariats and other items from rawhide. They were soaking the rawhide in the pool that was already low due to dry weather. The rangers, who had been searching for water for some time, were horrified to find that the water was a seething mass of hair, maggots and rotting flesh. Wallace, Westfall, and ten of their men rode to the upper waterhole only to find the Indians waiting to give battle.

Wallace returned to the first water hole, gathered his men, and left. He waited for the Indians to retreat from the camp that afternoon before moving back in to get water for his horses and men. This fight resulted in three wounded rangers, and seven Indians killed, including the old chief.59 The wounded rangers were taken to the hospital at Fort Inge, and the other men returned to the ranger camp at Edward Westfall’s ranch, twenty-seven miles below Fort Inge60 on the Leona River.61 Among the sick and wounded men were Linden Jackson, Rufus Halyard,62 Ephraim Rose, and Louis Oget.63

The fight at Black Hills and the story of the Mier Expedition were two of Wallace’s most famous stories. Newspaper reporter A. J. Sowell recorded one version of the fight at Black Hills in his book, “Life of “Big Foot” Wallace.” The Kerrville Mountain News edition of May 6, 1926, reprinted another extended version of the fight “in Wallace’s own words.”64

Two weeks after the fight at Black Hills, on August 5, 1850, Wallace and 23 rangers fought and vanquished 125 Indians on the Laredo road. The fight lasted seven hours and resumed the next day, resulting in 20 Indians killed and 65 captured.65

The results of the 1850 campaign were unsatisfactory.

Despite the military’s best efforts to control the Indians, on July 26, 1850, the citizens of San Antonio met and passed a resolution declaring that the area between the Guadalupe River and the Rio Grande was infested and overrun with hostile savages.66 A similar petition was sent to General Brooks from Corpus Christi on August 15. Reports also came in of Indian attacks near Corpus Christi, Laredo and Eagle Pass.67

General Brooks found it almost impossible to procure sufficient horses in Texas, and he had been able to mount only one-half of the regular infantry. For this reason, he felt compelled to continue the service of the four mounted companies of volunteer rangers despite the problems they caused him. The Adjutant General R. Jones observed that “great negligence was observed in the volunteers (rangers) in Texas in respect to muster rolls and returns required by the regulations, etc.”68 Only Captain John S. Ford, whose company was assigned to Fort McIntosh, submitted reports of combat actions. While the Texas ranging companies were organized as military units, their outlandish dress, long beards, and errant behavior clearly distinguished them from federal soldiers.69 Despite General Brooks’ initial high opinion of the rangers,70 their refusal to act responsibly ultimately led to their dismissal from Federal Service. His experience with the Texas rangers mirrored that of General Zachary Taylor, who ended the Mexican War very disenchanted with them. Their refusal to wear uniforms and salute officers and their tendency to prey upon Mexican civilians had been very upsetting to General Taylor.71

Despite General Brooks’ increasingly dim view of the rangers, on approximately August 23, 1850, Wallace’s company was mustered into service for a second term. In total, this company served for almost 1½ years in three consecutive 6-months terms. The enlistment term of Ford’s, Grumble’s, and McCown’s companies also expired between August 23 and September 23, 1850. All four companies were mustered in for another term.72 Captain Grumble’s company mustered in in September with a new captain, James D. Bagby, after Captain Grumble died.73 Not all the men re-enlisted, some were killed or wounded, and new men were continually being recruited to keep the companies fully manned.74 When the Federal population census was taken on October 14, 1850, Thomas Rife was at Fort Inge in Bexar County on the Leona River with Wallace’s ranging company. He, or someone representing him, wrongly listed his age as 25 and stated that he was born in Mississippi.75

Late in 1850, General Brooke added one more ranging company to his command for a total of five companies. On November 4, 1850, Henry McCulloch organized a company to be mustered into federal service to serve for 12 months. An article in a newspaper on October 26, 1850, announced the details. All desiring to join met in Austin on November 4 with his horse, saddle, bridle, blanket, and clothing.76 Lieutenant Thomas J. Wood of the US Army then mustered the company into Federal service. Henry McCulloch was elected Captain with John R. King as his First Lieutenant and Calvin S. Turner, Second Lieutenant. The company was stationed in Refugio County on the Gulf coast in the neighborhood of the port town of Lamar on Aransas Bay.77

On March 23, 1851, the second six-month term of enlistment of Wallace’s company expired. General Brooke requested, on February 7, 1851, that the Governor allow him to muster this company into Federal service for another six-month term if the men were agreeable to doing so. He made the same request of the companies commanded by Bagby, Ford, McCown, and McCullough, all of whose enlistments were to expire between March 5 and May 5, 1851.78

General Brooke dismissed the ranging companies in 1851.

In the fall of 1851, General Brooke decided to end the experiment with State troops. He may have felt that he had achieved his goal of pushing the Indians west of the line of forts, or he may have realized the impossibility of doing so. Two other factors may have prompted General Brooke to change his strategy. After Congress voted to pay Texas to settle its land claims in New Mexico Territory in 1850, every appropriation involving Texas came under intense scrutiny. Congress would have denied further funding for the employment of State troops if Congress believed Federal infantry troops could do the same job at half the cost.79 Another factor involved the often erratic and unprofessional behavior of the rangers.80 The ranging company stationed near Rio Grande City (opposite Camargo) became involved as mercenaries in the so-called Merchant War. Their actions angered the Governor81, and General Brooke dismissed all five companies of Texas rangers in federal service after that incident. On September 23, 1851, after the third six-month term of service expired, the experiment ended, and Wallace’s Company mustered out after a year and a half of service.82

-

Walter Prescott Webb, The Texas Rangers: A Century of Frontier Defense, (Austin: University of Texas at Austin, 1965), 144 ↩︎

-

David P. Smith, Frontier Defense in Texas: 1861-1865, (Denton, TX: North Texas State University, 1987), 283 ↩︎

-

Thomas T. Smith, The Old Army in Texas: A Research Guide to the US Army in Nineteenth-Century Texas, (Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 2000), 5 ↩︎

-

Ivey, The Texas Rangers: A Registry and History, 77 ↩︎

-

David P. Smith, Frontier Defense in Texas: 1861-1865, 5 ↩︎

-

Smith, The Old Army in Texas, A Research Guide to the US Army in Nineteenth-Century Texas, 15 ↩︎

-

Smith, The Old Army in Texas, A Research Guide to the US Army in Nineteenth-Century Texas, 98-9 ↩︎

-

Indian Papers: Geo. M. Brooke to PHB (June 6, 1850), Records of P. Hansborough Bell, Texas Office of the Governor, Archives and Information Services Division, Texas State Library and Archives Commission ↩︎

-

T. R. Fehrenback, Comanches: The Destruction of a People, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1974), 306; Gwynne, Empire of the Summer Moon, 74 ↩︎

-

Bender, “Opening Routes Across West Texas, 1848-1850”, 129 ↩︎

-

Thomas T. Smith, ”Fort Inge,” Handbook of Texas Online, (http//www.tshaonline.org/handbook.online/articles/qbf27), accessed December 05, 2010. ↩︎

-

Smith, “Fort Inge,” Handbook of Texas Online ↩︎

-

Middle Rio Grand Development Council, Uvalde County, www.mrgdc.org/cog/cog_region/uvaldecounty.php#inge, accessed Aug 26, 2012, 7 ↩︎

-

Smith, “Fort Inge,” Handbook of Texas Online ↩︎

-

Dick Whipple, “Fort Inge, A History, A Soldier’s Life in Frontier Texas, The Fort Today”, Branches and Acorns 18, Southwest Texas Genealogical Society, No. 4, (June 2003), 7 ↩︎

-

L. Crimmins, ed., “W. G. Freeman’s Report on the Eighth Military Department,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 53, No. 1 (July 1949), 75 ↩︎

-

Smith, “Fort Inge,” Handbook of Texas Online ↩︎

-

Smith, Frontier Defense in Texas: 1861-1865, 3, 7 ↩︎

-

Texas State Gazette, (Austin), November 24, 1849 ↩︎

-

Texas State Gazette, (Austin), August 25, 1849 ↩︎

-

Smith, The Old Army in Texas, A Research Guide to the US Army in Nineteenth-Century Texas, 21 ↩︎

-

Texas State Gazette, (Austin), August 25, 1849 ↩︎

-

Geo. M. Brook to GTW (August 11, 1849), Records of George T. Wood, Texas Office of the Governor, ARIS-TSLAC; Ivey, The Texas Rangers: A Registry and History, 75; Texas State Gazette, (Austin), August 25, 1849 ↩︎

-

Texas State Gazette, (Austin), August 25, 1849 ↩︎

-

Order 57 from General George Deas (August 19, 1849), Records of George T. Wood, Texas Office of the Governor, ARIS-TSLAC ↩︎

-

Webb, The Texas Rangers, 141 ↩︎

-

Texas State Gazette, (Austin), October 26, 1850 ↩︎

-

Order 57 from General George Deas (August 19, 1849) ↩︎

-

Texas State Gazette, (Austin), October 26, 1850 ↩︎

-

Order 57 from General George Deas (August 19, 1849) ↩︎

-

Indian Papers: S.M. Plummer to Maj. Geo. Deas, Governors Papers, (September 5, 1850) ARIS-TSLAC; James Farber, Texas, C.S.A.: A Spotlight on Disaster, (New York and Texas: The Jackson Co., 1947), 69 ↩︎

-

Texas State Gazette, (Austin), October 26, 1850 ↩︎

-

Order 57 from General George Deas (August 19, 1849) ↩︎

-

Order 57 from General George Deas (August 19, 1849) ↩︎

-

Geo. M. Brooke to PHB, (March 6, 1850), Records of P. Hansborough Bell, Texas Office of the Governor, ARIS-TSLAC ↩︎

-

Geo. M. Brook to GTW (August 11, 1849) ↩︎

-

Order 57 from General George Deas (August 19, 1849); Texas State Gazette, (Austin), October 26, 1850 ↩︎

-

Smith, Frontier Defense in Texas: 1861-1865, 6 ↩︎

-

Order 57 from General George Deas (August 19, 1849) ↩︎

-

Oates, editor, Rip Ford’s Texas, 143 ↩︎

-

Geo. M. Brooke to PHB, (March 6, 1850) ↩︎

-

Webb, The Texas Rangers, 141; Texas State Gazette, (Austin) March 9, 1850 ↩︎

-

Gen. Hamey, Special Orders 3 (March 23, 1850), Records of P. Hansborough Bell, Texas Office of the Governor, ARIS-TSLAC ↩︎

-

Geo. M. Brooke to PHB, (March 6, 1850); Webb, The Texas Rangers, 141 ↩︎

-

Gen. Hamey, Special Orders 3 (March 23, 1850) ↩︎

-

Frederick Wilkens, Defending the Borders, The Texas Rangers, 1848-1861, (Austin: State House Press, 2001), 16 ↩︎

-

James Pike, Scout and Ranger being the Personal Adventures of James Pike, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1932), 22 ↩︎

-

Geo. M. Brooke to PHB (March 6. 1850) ↩︎

-

Ivey, The Texas Rangers: A Registry and History, 86 ↩︎

-

Geo. M. Brooke to PHB (March 6. 1850) ↩︎

-

Florence Fenley, “Events in the Early History of Uvalde County”, The Uvalde Leader News, (Uvalde, Texas), May 06, 1956 Centennial Edition, 111 ↩︎

-

Fenley, “Events in the Early History of Uvalde County,” 110 ↩︎

-

Indian Papers: Gen.. Brooke, military order 27 (June 1, 1850) typescript, Records of P. Hansborough Bell, Texas Office of the Governor, ARIS-TSLAC ↩︎

-

Indian Papers: Gen.. Brooke, military order 27 (June 1, 1850) typescript, Records of P. Hansborough Bell ↩︎

-

Williams, Never Again, Texas: 1848-1861, 58 ↩︎

-

Williams, Never Again, Texas: 1848-1861, 155 ↩︎

-

J.W. Wilbarger, Indian Depredations in Texas, Reliable Accounts, (Austin: Hutchings Printing House, 1889), 671 ↩︎

-

Wilbarger, Indian Depredations in Texas, Reliable Accounts, 671; Smith, The Old Army in Texas, A Research Guide to the US Army in Nineteenth-Century Texas, 138; Texas State Gazette, (Austin), August 31 1850; A.J. Sowell, Life of “Big Foot” Wallace, The Great Ranger Captain, (Austin: State House Press, 1989), 155-162; Wilkens, Defending the Borders, The Texas Rangers, 1848-1861, 16 ↩︎

-

Williams, Never Again, Texas: 1848-1861, 58 ↩︎

-

Williams, Never Again, Texas: 1848-1861, 162 ↩︎

-

Fenley, “Events in the Early History of Uvalde County,” 110 ↩︎

-

Williams, Never Again, Texas: 1848-1861, 162 ↩︎

-

Wilbarger, Indian Depredations in Texas, 671 ↩︎

-

The Kerrville Mountain Sun, May 6, 1926 ↩︎

-

Charles Merritt Barnes, Combats and Conquests of Immortal Heroes, (San Antonio: Guessaz & Ferlet Company, 1910), 187; Miss Mattie Jackson, The Rising and Setting of the Lone Star Republic, (San Antonio: unknown publisher, 1926), 189 ↩︎

-

Williams, Never Again, Texas: 1848-1861, 58 ↩︎

-

Geo. M. Brook to GTW (August 11, 1849) ↩︎

-

Williams,* Never Again, Texas: 1848-1861,* 59; ↩︎

-

Ivey, The Texas Rangers: A Registry and History, 59; Gwynne, Empire of the Summer Moon, 138 ↩︎

-

Order 57 from General George Deas (August 19, 1849) ↩︎

-

Seymour V. Connor, Adventures in Glory: The Saga of Texas, 1836-1849, (Austin, Texas: Steck-Vaughn, 1965), 250 ↩︎

-

Indian Papers: Geo. M. Brooke to PHB (August 10, 1850), Records of P. Hansborough Bell ↩︎

-

Indian Papers: S.M. Plummer to Maj. Geo. Deas (September 5, 1850) ↩︎

-

Indian Papers: S.M. Plummer to Maj. Geo. Deas (September 5, 1850); Greer, Colonel Jack Hays, 42 ↩︎

-

Thomas Rife, US Seventh Census (1850), Bexar County, TX; Mrs. Lauretta Russell, 1850 Census of Bexar County, TX, 77 ↩︎

-

Texas State Gazette, (Austin), October 26, 1850 ↩︎

-

Texas State Gazette, (Austin), November 9, 1850 ↩︎

-

Indian Papers: Geo. M. Brooke to PHB (February 7, 1851), Records of P. Hansborough Bell ↩︎

-

Smith, The Old Army in Texas, A Research Guide to the US Army in Nineteenth-Century Texas, 19 ↩︎

-

The Western Texan, (San Antonio), July 31, 1851 ↩︎

-

Webb, The Texas Rangers, 141-2 ↩︎

-

Texas State Gazette, (Austin), September 20, 1851 ↩︎