Rife began a career as a stage conductor

“…he was mustered out to form captain of one of the parties carrying the first mail from San Antonio to Santa Fe. Big Foot Wallace was captain of the other party, and for nearly three years he was so engaged. In those days there was no house nor settlement between Joe Ney’s ranch (70 miles west of San Antonio, editor) and San Elizario, a distance of 800 miles, and the party was an armed force on a road that was beset by Indians, and much could be written of the dangers and vicissitudes of his position.”

— “Custodian of the Alamo,” San Antonio Light, February 23, 1887.

Henry Skillman was a legendary figure in West Texas.

Henry Skillman was born in New Jersey in 1814, spent his youth in Kentucky, and came to Texas before 1839. He worked as a courier on the Santa Fé Trail and as a wagon master. He was a scout for Colonel Alexander Doniphan when the United States was at war with Mexico in 1846 and accompanied Colonel Doniphan’s expedition to Chihuahua as it followed the Santa Fé Trail south from El Paso del Norte. Skillman was at the February 28, 1847 battle at Sacramento, Chihuahua as captain of a company of wagon masters and teamsters.1 A year later, he was again serving as a scout and fought at the Battle of Santa Cruz de Rosales on March 16, 1848. After the Mexican War, he settled in Franklin, one of the villages that became El Paso, Texas, and operated a freight line between there and San Antonio.

Henry Skillman was described as “a great blond giant with flowing beard and hair - — the Kit Carson of Big Bend.” 2 A reporter for the San Antonio Ledger wrote in October 1853, “Prominent in uncouthness was the Captain himself, with his beard descending some foot and a half below his countenance.” 3 Skillman was dangerous when drunk. On rare occasions while under the influence of “strong drink” he would “shoot up the town.” After he was sober, he would “return to the scene of his exuberance, pay the damages, and apologize to everyone for his actions.” 4 This behavior cost Skillman $25 and court costs in San Antonio in February 1853. The Mayor’s Court fined him for “Assault and Battery, Furious Riding, Riding on the Sidewalk and Obstructing an Officer.” 5

Skillman helped layout the San Antonio to El Paso Road.

After the war with Mexico ended, the US Army began locating and mapping roads to the newly acquired territories in the Southwest. Lieutenant William Whiting led an expedition that left San Antonio in February 1849 and reached the American settlements across from El Paso del Norte two months later. In April 1849, Lt. Whiting hired Henry Skillman at San Elizario to purchase supplies for the expedition’s return trip to San Antonio. Skillman located and purchased the necessary supplies in the village of Doña Ana, then in Texas, and the small Mexican town of Presidio del Norte (now Ojinaga, Chihuahua). Skillman then caught up with the Whiting party near what became the Lancaster Crossing of the Pecos River and accompanied the soldiers and their guides back to San Antonio.6

Stage service to south Texas from San Antonio had begun the year before;7 no stages were running west of San Antonio, however. The Comanche and Mescalero Apache Indians and the lack of an established route made travel west of San Antonio extremely dangerous.8 Nevertheless, by the time California was admitted as the thirty-first state on July 9, 1850, US Army surveyors had located and improved the best routes for roads through the Trans-Pecos region of West Texas.9 The road investigated in 1849 by Lieutenants S.G. French, and William Whiting became known as the Military or Lower San Antonio to El Paso road. The route was an all-season road, over a natural surface, rough in places but free of snow in the winter.10 For the most part, this was the route used by the first mail service to west Texas.

Skillman’s first contract for mail service was from 1851 to December 1852.

Before 1851, mail to points west of San Antonio was carried by either US Army express riders or by private couriers such as Henry Skillman.11 US citizens living in the cluster of settlements on the east bank of the Rio Grande across from El Paso del Norte signed a petition dated September 10, 1850, urging the establishment of postal service between there and San Antonio, possibly following a route through Fort Inge and Presidio del Norte. The newspaper editor who published the petition notice somewhat optimistically predicted that the trip could be made in 16 days without relay stations. He calculated that with “some few posts upon the road, to furnish relays of horses,” the trip could be made in half that time.12 While the far-sighted editor was correct in some respects, it would be three years before any relay stations existed on this road.13 He also underestimated the length of the journey; even after relay stations were built, the trip by stagecoach took 16 days.14

Congress passed a bill that made mail service more practicable on March 3, 1851. On that date, Congress authorized the US Mint to produce a 3-cent coin for the express purpose of purchasing postage stamps.15 Congress also lowered postage fees dramatically16, and by the summer of 1851, the prerequisites for mail service to west Texas were in place. The Topographical Engineers had made a suitable road west of San Antonio, and also Congress had made postage affordable. The California gold rush increased the volume of trade between the eastern states and the Pacific coast and created a demand for passenger and mail service to California.17 In response to the growing public need, the Post Office Department placed notices in newspapers seeking bids for mail service on Route /#6336. This semi-monthly route was to run from San Antonio through Eagle Pass, Presidio del Norte, and El Paso County, Texas, to Doña Ana in New Mexico Territory.18

Before receiving the mail contract, Skillman ran a courier service.

Before September 1851, Henry Skillman, along with William “Big Foot” Wallace and his friend Edward Westfall, was operating a private courier service based in San Antonio. It was an irregular service for private subscribers.19 Wallace and a partner submitted a bid for the new mail route, but their bid was rejected as too costly.20 Henry Skillman saw the mail service as an opportunity to continue his courier service on a sounder basis and with a guaranteed income large enough to buy coaches and to hire help. He was determined to get the contract that had been denied to Wallace and Howard earlier in the year. In September 1851, Skillman traveled by steamship from New Orleans to Washington, DC, where he negotiated directly with the Postmaster General.

Skillman successfully negotiated the stagecoach contract; on September 20, 1851, he signed Contract Number 6401 with Postmaster General Nathan K. Hall to carry mail between San Antonio and Santa Fé via Franklin in El Paso County, Texas. The contract was to begin on November 1, 1851, and to expire on June 30, 1854. Skillman was to be paid $12,500 per year for carrying the mail in his coaches.21

Notice of the contract appeared in The National Intelligencer, a Washington, DC newspaper. The reporter prophesized that the contractor would lose money on the route. He stated that “the transportation of mails through a vast unsettled wilderness, infested by roaming bands of rude and often hostile Indians, must, to afford them (the mail carriers) the proper protection, be attended with an expense far beyond any possible receipts.” 22 A decade of mail service would prove the reporter to be correct. It was always a dangerous undertaking to travel across the Texas wilderness, but it was especially dangerous for a lone courier or a small party even if they were heavily armed and riding fresh horses. The problem was that every traveler, whether Anglo, Mexican or Indian, had to stop at the same watering places, and therefore encounters with Native Americans were inevitable.23

The first mail to Santa Fé left San Antonio in November 1851.

After Skillman returned to San Antonio from Washington, D. C., the first westbound mail coach left San Antonio on either the first or the third of November 1851. The trip took three weeks, and the mail arrived in Santa Fé on November 24.24

The first southbound coach left Santa Fé on January 2, 1852, and arrived safely in San Antonio. The same coach was dispatched on the second westbound trip to Santa Fé but failed to reach its destination. A search party discovered the charred remains of the mail coach in the mountains downriver of El Paso. The driver was assumed to be dead since nothing was found of him but his hat.25 This would be the first of many similar attacks on Skillman’s coaches.

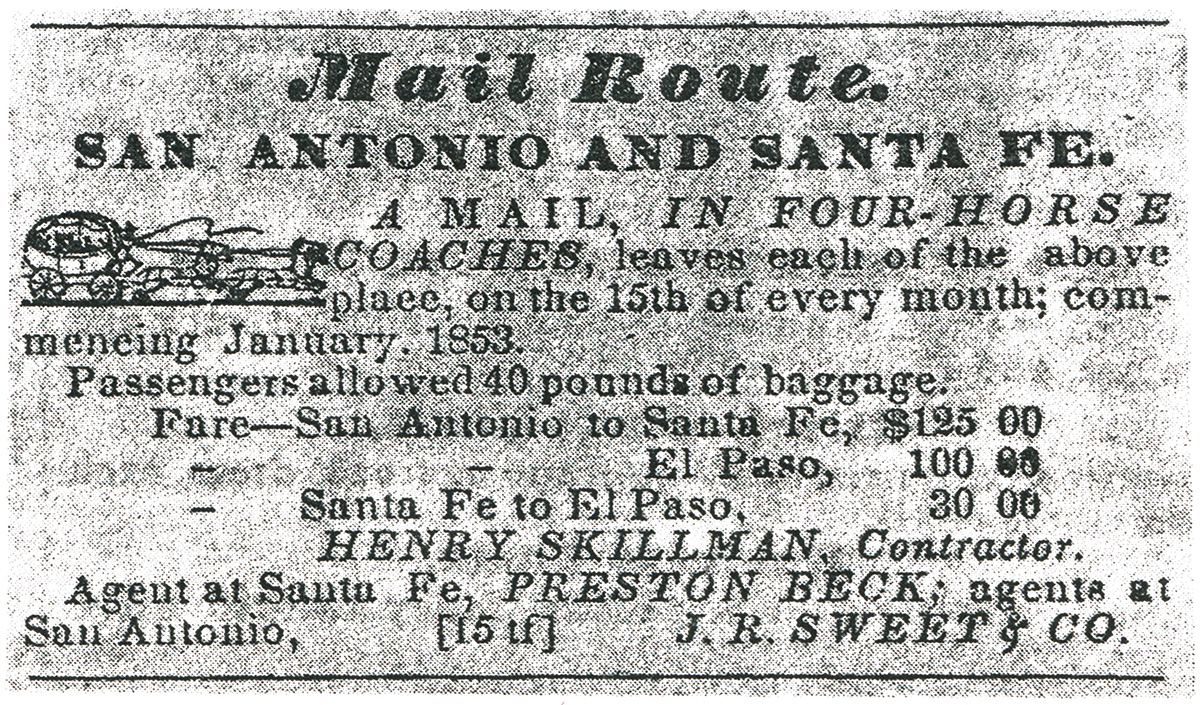

Skillman ordered some “good comfortable spring carriages for the accommodation of passengers” while in Santa Fé26, and on December 6, 1851, a newspaper advertisement announced the start of passenger service. According to Skillman’s advertisement, “The mail will leave Santa Fé on the second of each month… and arrive in San Antonio on the last day of the same month.” The westbound coach will “leave San Antonio on the first of each month … and arrive in Santa Fé on the last day of the same month.” Skillman stated that the greatest distance between watering places was forty miles and that,” he will also have on the line a small train of light wagons.” The passenger fare for the full trip between Santa Fé and San Antonio was $125.27 In addition to mail and passengers, the coaches brought newspapers and gossip between the civilized world and the west.28 In September 1853, the train led by Captain Wallace brought “some fine specimens of the El Paso grape, upon which those of our citizens, who were favored with ‘bunches’, were luxuriating with infinite satisfaction.” 29

Skillman built at least two relay stations along the mail route. One was at San Elizario and the other at the Leona River, near present-day Uvalde.30 On the night of January 25, 1852, Indians stole mules and horses (numbering between 30 and 40) from the corral at the Leona Station, the first relay station west of San Antonio. The mules belonged to San Antonio merchant George Giddings (who was camped there) and Henry Skillman’s mail service.31 Some of the horses escaped from the Indians during the night and returned to the corral.

Thomas Rife and Edward Westfall, both employees of the mail service, and a few other men who lived in the area started on the trail of the Indians the next morning.32 They caught up with the raiders, killed one, and let the others flee. All the stolen horses and mules were recovered.33 On that same day, Apaches attacked the coach running between Santa Fé and El Paso and killed three men. The coach was being escorted by soldiers from the US Army Second Dragoons and was abandoned and later destroyed by the Indians.34

Thomas Rife was an employee of the mail service.

On September 23, 1851, the 100 or so men remaining in Wallace’s ranger company mustered out of Federal Service. Rife had left the service sometime before September 1851. He and several men from Wallace’s company continued living along the Leona River in the vicinity of the ranger camp where they had lived while in Federal service.

In the first few months after having been awarded the mail contract in the spring of 1852, Skillman hired William “Big Foot” Wallace, Edward Westfall, Thomas Rife, Louis Oge, Bradford Daily, Benjamin Sanford, Adolph Fry, and others to carry the mail.35 Rife continued in this service for eighteen months. Initially, only one coach was making the two-month-long round trips between San Antonio and Santa Fé. Big Foot Wallace and Rife worked together manning the coach until January 1853, when the frequency of the trips increased, and Rife and Wallace each led a team going in opposite directions.36

The Texas State Gazette reported that on September 9, Comanche Indians attacked Big Foot Wallace, Thomas Rife, Adolph Fry, and three other men carrying the mail to El Paso. The three wagons, outfitted to carry passengers and referred to as “ambulances,” were attacked at Big Bluff, between California Springs and Painted Caves, an area located between the first and second crossing of the Devils River. When the Indians attacked, the coachmen had just finished their mid-day siesta and were harnessing the mules for the afternoon march. Twenty-seven Comanche shot at the wagons from a nearby bluff. The fight continued all afternoon. The guards used long-range rifles to kill five of the attacking Indians, but fearing that the Indians would attack again, the mail party returned to Fort Clark to obtain a military escort. After failing to get an escort, Wallace hired three extra men at Leona Station and continued the effort to get the mail through.37

The second contract for mail service ran from 1853 to June 1854.

For the first year of the two and a half year contract, the mail was to be transported each way every other month. Soon the volume of mail was significant enough to require monthly service. On October 2, 1852, Skillman left El Paso County for Washington, D. C. to upgrade his contract, arriving in Washington City by December 2; a few days later, a new contract was signed. It specified that a mail train was to leave both San Antonio and Santa Fé in the middle of each month.38

While on the trip to see the Postmaster-General, Skillman visited the Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company in Hartford, Connecticut. When the American Boundary Survey Commission passed through the El Paso area in 1850, Skillman saw and admired the 1849 model of the Sharps Beech-loading Rifle.39 A new model (most likely the model 1852 carbine) was now available, and Skillman bought a case of ten rifles.40 Often, this new weapon gave the mail carriers the upper hand over Indian raiders.41 The Sharps Rifle helped to speed the advance of the white men into land that had once been the Indian’s domain.

Monthly service began in 1853.

On January 20, 1853, Skillman announced mail service with monthly passenger service. Four-horse coaches would leave both Santa Fé and San Antonio on the fifteenth of every month. Bigfoot Wallace was in command of one of the mail trains, and Rife was in charge of the other. For the remainder of 1853, the two men maintained this schedule with each man making the round trip every two months.

January and February 1853 were quiet months, and the mail carriers frequently set new time records.42 In short order, the speed record was broken again on April 14, 1853, when Thomas Rife arrived in San Antonio from San Elizario in 13½ days.43 The distance between San Elizario and San Antonio was about 628 miles, so the coach averaged 46½ miles per day.

In those days, there were no relay stations between Fort Clark and San Elizario, a distance of about 500 miles. A large remuda (herd) of relief mules was driven along, and teams were changed frequently. The mules traveled the entire distance with only short stops for rest and feeding. The team pulling the wagon was also changed frequently to give the mules some relief. However, the men driving them worked straight through, traveling day and night to meet the schedule. The day was divided up into three equal parts. The mail train would “travel fifteen or more miles in each division, thus averaging about fifty miles a day.” 44 The San Antonio Light edition of August 2, 1902, described a typical trip. “Along this weary stretch of country, the party camped where night overtook them.” It “usually took twenty to twenty-four days. Indian fights were common, and the passengers had to take their turn on guard and in doing camp chores.” 45 The Indian raiding parties were looking for horses and mules, so the large numbers of relief mules being herded behind the mail trains were an enormous temptation to them.

Rife’s mail train left San Antonio on April 15, 1853, and camped at Van Horn’s Well on April 28. He passed Wallace’s coach making the eastbound trip to San Antonio a little while before arriving at the Well. Wallace’s train was ambushed twelve miles south of Van Horn’s Well; the mules stampeded, and Benjamin Sanford was shot in the side by an arrow. His comrades broke off the shaft of the arrow, rounded up all but four of the mules, and returned to Van Horn’s Well to deliver the wounded man to Rife, who took him to El Paso. Sanford “succeeded in reaching the settlements at San Elizario before he breathed his last. He died among friends and comrades.” 46

Wallace arrived in San Antonio on May 9, 1853, in less than 14 days and reported a second night attack at the Pecos River.47 A war-chief known as Yellow Wolf was “in the neighborhood,” so it was supposed that a portion of his band had attacked the mail train.

Working in the mail service was hazardous.

John G. Walker, captain of a company of US Mounted Rifles stationed along the mail route, testified in later years that, “Predatory bands of Indians were constantly making incursions into the country, crossing these roads, and taking occasion to kill and scalp and to plunder either the mails or anybody else that might be within their reach.” He also said that he “always wondered that anybody would undertake to carry the mail, considering the danger of the employment. It was always a mystery to me that he (Giddings) could employ men who would take their lives in their hands to carry out that contract.” 48

William W. Mills, a prominent citizen of El Paso, described the typical stage driver after Mills had made a trip from El Paso to San Antonio. According to Mills, the stage driver “possessed the courage of the soldier and something more. The soldier goes where he is told to go, and fights when he is told to fight, but he has little anxiety or responsibility. The stage driver, on the other hand, had to be as alert and thoughtful as a general. There was not only his duty to his employers but his responsibility for the mails (he was a sworn officer of the Government); and the lives of passengers often depended upon his knowledge of the country and the Indian character, as well as his quick and correct judgment as to what to do in emergencies. Like the sailor, he was something of a fatalist; but he believed in using all possible means to protect himself and those under his charge.” 49

Rife arrived at San Antonio on June 9, 1853, leading a train consisting of “two ambulances, twenty-two mules and eight men, the latter of which are all noted for their valor and frontier exploits.” He left for Santa Fé on June 15.50 The San Antonio Ledger published a letter from a regular contributor in El Paso that included a glowing and verbose testimonial to Tom Rife’s work as a coach conductor. It read, “Tom Rife arrived here with the last mail from your place (San Antonio) on the evening of June 29, being six days ahead of his time. I know of no one in whose character is combined to so full an extent all those elements necessary to ensure a successful prosecution of this hazardous and tedious business than Tom; his speed on this route is as yet unexcelled, and his care and vigilance while on the road unquestioned.” 51 Rife’s return trip to San Antonio was made in twelve days, and nine hours, “fast time, you will acknowledge” in the words of the New Orleans Picayune correspondent.52

Rife returned to San Antonio on August 7 and then had seven days off. The faster the trip, the more time in San Antonio the stage crew was allowed. This may have been what motivated the mail carriers to shorten the time on the trail.53

By August 1853, Skillman was back in Washington City to get his contract extended through June 30, 1854.54 It appears that he successfully renegotiated the contract, as the mail trains kept running.

Thomas Rife married Mary Ann Arnold in 1853.

Rife carried the mail from El Paso to San Antonio on October 11, 1853, after a trip of 16 days.55 Three days after Tom’s arrival, on October 14, Tom Rife and Mrs. Mary Ann Arnold Brothers were married. The journey's departure, scheduled to leave San Antonio on the 15th, was delayed due to the mail arriving late from the coast.56 This delay allowed Tom and Mary a two-day honeymoon before he left with the mail train for El Paso.

Tom Rife brought the mail and eight passengers into San Antonio from Santa Fe on December 10, 1853. He required 15 days to make the trip reported to be “a very pleasant one for this season of the year.” 57 This is the last mention of Rife as a mail conductor until December 8, 1858, a span of almost five years.58 Mary Ann Arnold said in her petition for a divorce dated February 4, 1860, that he left for California on December 27, 1853, and did not return for more than three years.59

Skillman was having trouble making up for constant financial losses due to Indian depredations. On February 4, 1854, he mortgaged “100 mules and four coaches which are now being used in the conveying of the mail…” to James “Don Santiago” Magoffin, a merchant with a store at Magoffinsville (now El Paso). Skillman sold his house and lot in Concordia (now part of El Paso) and consigned a draft due from the Post Office worth $7,000.60 As the reporter had predicted two years earlier, the mail route was a losing proposition for the contractor.

Skillman’s losses continued on February 27, 1854, when Indians stole mules belonging to Skillman from the corral at Leona Station at Uvalde. Three days later, the party sent to recover the mules returned to Uvalde, having recovered ten mules from the Indians.61 Horses were also taken from the stable-yard at the army post at nearby Ft. Inge.62

In 1854, US Army General Persifor Smith, commander of the Department of Texas, selected sites for a string of forts as recommended by the Army inspector the previous year.63 The new forts were intended to provide escorts for the mail haulers and protection for freighters and travelers on the San Antonio to El Paso Road. These forts, including Fort Davis and Fort Lancaster, were staffed with Infantry mounted on mules. In October 1854, troops of the 8th Infantry arrived from Ringgold Barracks on the lower Rio Grande to build the post at Fort Davis.64 While these forts came too late to benefit Henry Skillman, the mail contractor at that time, they would be of great importance to the next mail contractor.

William Wallace and Bradford Daily (who replaced Tom Rife) were conductors for Skillman during the final months of his contract.65 Wallace brought the mail into San Antonio during March 1854, and Daily did the same during April.66

June 30, 1854, was the last day of Henry Skillman’s contract. To continue the service, he bid on a new contract for route #12900 for either two-horse or four-horse service to begin on July 1 and run monthly each way between Santa Fé and San Antonio. His bid of $24,900 was rejected. Other bidders were Jacob Hall, McGraw and Reeside, and David Wasson from Lewistown, Pennsylvania. The Postmaster General accepted Wasson’s bid for a two-horse service on April 22, 1854. His bid of $16,75067 would prove to be too low for the service expected68 and would lead to much grief for George H. Giddings over the next three years as the eventual mail contractor.

James Magoffin, who had loaned Skillman money, shared in Skillman’s losses. As early as November 1854, Isaac Lightner, a merchant in El Paso County, had urged Magoffin to seize Skillman’s mules69 in payment of the debt but Magoffin, perhaps realizing how vital the mail service was to El Paso or perhaps out of fear of Skillman,70 delayed any action. In 1858, Magoffin finally agreed to sue Skillman but was advised that it was too late, and besides, “I can’t even get $32…out of him (Skillman).” 71 As George Giddings said, and as the Washington, DC newspaper reporter had predicted, Henry Skillman was financially ruined by the mail service.

-

Wayne R. Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules: The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, 1851-1881, (College Station, TX: Texas A & M University Press, 1985), 20 ↩︎

-

Carlysle Graham Raht, Romance of Davis Mountains and Big Bend Country, A History, (El Paso: The Rahtbooks Company, 1919), 150 ↩︎

-

The San Antonio Ledger November 4, 1852 ↩︎

-

Raht, Romance of Davis Mountains and Big Bend Country, A History, 151 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Ledger February 10, 1853 ↩︎

-

Clayton Williams, Never Again, Texas 1848-1861 Vol. 3, (San Antonio: The Naylor Co., 1969), 21; Ralph P. Bieber, editor, Exploring Southwestern Trails 1846-1854, Journal of William Henry Chase Whiting, 1849, (Glendale, CA: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1938), 339 ↩︎

-

Robert H. Thonhoff, San Antonio Stage Lines: 1847-1881, (El Paso: Texas Western Press, 1971), 8, figure 3 ↩︎

-

Robert H. Thonhoff, San Antonio Stage Lines: 1847-1881, 9 ↩︎

-

Jack C. Scannell, “A survey of the Stagecoach Mail in the Trans-Pecos, 1850-1861”, West Texas Historical Association Year Book 47, (1971), 117 ↩︎

-

Letter from General P. F. Smith, George H. Giddings vs. the United States. Comanche, Kiowa and Apache Indians, case 3873, Indian Depredation Case Records, 1891-1918, Records of the Court of Claims, 1835-1966, RG123, National Archives and Records Administration ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules: The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, 1851-1881, 22 ↩︎

-

The Western Texan (San Antonio), September 19, 1850 ↩︎

-

Letter from General P. F. Smith, George H. Giddings vs. the United States. ↩︎

-

The Western Texan (San Antonio), October 13, 1853 ↩︎

-

Texas State Gazette (Austin), March 1, 1851; Silver Three Cents: 1851-1873, Type Set Coin Collecting, (http://typesets.wikidot.com/silver-3-cents), accessed June 3, 2011. ↩︎

-

Texas State Gazette (Austin), December 8, 1849 ↩︎

-

Scannell, “A survey of the Stagecoach Mail in the Trans-Pecos, 115 ↩︎

-

*The Northern Standard, (Clarksville, Tex.), March 8, 1851. ↩︎

-

Sacramento Daily Union, January 25, 1853 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 21 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 23 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 23 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 22 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 25-6 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 28 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 26 ↩︎

-

The Western Texan (San Antonio, Texas), November 4, 1852; Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 26; Thonhoff, San Antonio Stage Lines, 10, fig. 5 ↩︎

-

The Zanesville Courier (Zanesville, OH), July 12, 1853 ↩︎

-

The Gonzales Inquirer (Gonzales, TX), September 24, 1853 ↩︎

-

Florence Fenley, Oldtimers, Their Own Stories, (Austin, TX: State House Press, 1991), 213 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 29 ↩︎

-

Fenley, Oldtimers, 213 ↩︎

-

Fenley, Oldtimers, 213 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 29 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 28; James M. Day, “Big Foot Wallace in Trans-Pecos Texas,” West Texas Historical Association Year Book, 1979) Vol: LV 74; San Antonio Light, March 9, 1892 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Light, February 23, 1887 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 30-31; Texas State Gazette (Austin), September 25, 1852 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 31; Charleston Courier, (Charleston, SC.), December 14, 1852 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 32 ↩︎

-

Sacramento Daily News, April 12, 1854 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 33 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 33 ↩︎

-

Texas State Gazette (Austin), April 16, 1853; Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 34 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 38-39; Augusta Chronicle (Augusta, GA), July 12, 1853 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Sunday Light, August 2, 1902 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Ledger and Texan, May 12, 1853; San Antonio Ledger and Texan, June 16, 1853 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Ledger and Texan, May 12, 1853; San Antonio Ledger and Texan, June 16, 1853 ↩︎

-

U .S. Court of Claims, Deposition of John G. Walker, Giddings vs. The United States. ↩︎

-

Raht, Romance of Davis Mountains, 191 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Ledger and Texan, June 16, 1853 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Ledger and Texan, June 16, 1853 ↩︎

-

Weekly Herald, (New York), September 9, 1853 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Ledger and Texan, August 11, 1853; San Antonio Ledger and Texan, October 10, 1853; San Antonio Ledger and Texan, October 13, 1853 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 43-4 ↩︎

-

The Western Texan (San Antonio), October 13, 1853; San Antonio Ledger and Texan, October 13, 1853 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Ledger and Texan, October 20, 1853 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Ledger and Texan, December 15, 1853 ↩︎

-

Deposition of Thomas Rife, George H. Giddings vs. The United States. ↩︎

-

The San Antonio Ledger and Texan, March 10, 1860 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 50 ↩︎

-

Ike Moore, arranger, The Life and Diary of Reading W Black: A History of Early Uvalde, (Uvalde, TX: The El Progreso Club, 1934), 41 ↩︎

-

Frederick Law Olmsted, A Journey Through Texas or a Saddle-Trip on the Southwestern Frontier, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1978), 299 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 48 ↩︎

-

Jack Lowery, “Guarding the Westward Trail’, Texas Highways Magazine 39, No. 9, (September 1992), 46-7 ↩︎

-

The Western Texan (San Antonio), February 16, 1854; Houston Telegraph, October 20, 1858 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Ledger and Texan, March 30, 1854; Texas State Gazette, (Austin), April 29, 1854 ↩︎

-

Letter from Postmaster General to Senator Rusk, George H. Giddings vs. The United States. ↩︎

-

Memorial of George Giddings, George H. Giddings vs. The United States; Statement from Giddings, George H. Giddings vs. The United States. ↩︎

-

Letter from Isaac Lightner to James Magoffin, November 25, 1854, James Magoffin File, The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin. ↩︎

-

Letter from John Crosby to James Magoffin, August 6, 1855, James Magoffin File. ↩︎

-

Letter from Isaac Lightner to James Magoffin, May 18, 1858, James Magoffin File. ↩︎