Mary Ann Arnold

On October 14, 1853, when Thomas Rife married Mary Ann Brothers, a San Antonio-born, widow, he was 30 years old, and she was 20. They were a mixed-race couple; Mary Ann’s father was an American man of color, and her mother was a Mexicana from New Mexico. Rife was an Anglo American and the son and grandson of slave owners.

The couple was mismatched in many ways. Rife worked as the conductor of a mail train, a hazardous occupation. He was on the road most of the time, usually for weeks at a time. (The round trip between San Antonio and El Paso County took a month). Many of his friends were coachmen, hard-bitten bachelors, some of whom never married at all or did so only in their old age. Many of Rife’s friends were gunmen who died with their boots on. Mary Ann had inherited a ranch, and she probably expected her husband to run it.

Mary Ann’s father was Hendrick Arnold.

Mary Ann’s father, Hendrick Arnold, immigrated to Texas with his parents in March of 1826 from Mississippi. Hendrick’s father was Daniel Arnold, and it appears that his mother, Rachel, was a woman of mixed race. Daniel and Rachel Arnold may have been forced by peer pressure to leave Mississippi for Texas, where they must have hoped to find a more tolerant and diverse population. Hendrick was referred to as a Negro, but his brother or half-brother, Holly, was not. There is no evidence that the children were legally freed by their father, as required by law, but they “acted in all capacities as free persons.” 1 The family settled in Stephen F. Austin’s colony on the Brazos River.2

When Hendrick first came to Texas, he impregnated one of his father’s slaves, a girl named Dolly, and produced a daughter named Harriet whom he held as a slave.3 So began a series of events that would end in a trial in the Texas Supreme Court and an act of the Legislature. The issue that interested the Court was that on August 9, 1846, Hendrick indentured Harriet for five years to James Newcomb of San Antonio for the sum of $750. She was to be freed at the end of the period, but both Hendrick and Newcomb died in the cholera epidemic of 1849. Several members of Hendrick’s family attempted to gain possession of Harriet from the administrator of Newcomb’s estate and finally filed a lawsuit to that end. The Supreme Court found that the Mexican Constitution in effect when Harriet was born in 1827 outlawed placing children born in Texas into slavery. The effect was to “declare free all children born of slave parents after May 29, 1827, and previous to the adoption of the constitution of the Republic” of Texas in 1836. Although this decision must have affected many people, Anglo Texans were in no mood to free any slave, and Harriet may have been the only person to benefit from the ruling.4

By the fall of 1835, Hendrick had married María Ygnacia Durán (who was Erastus “Deaf” Smith’s step-daughter) and settled in Béxar.5 María Durán was born in New Mexico. The couple’s first child, Mary Ann, was born in the village of Béxar on May 07, 1833, before her parents married, not unusual at that time.6

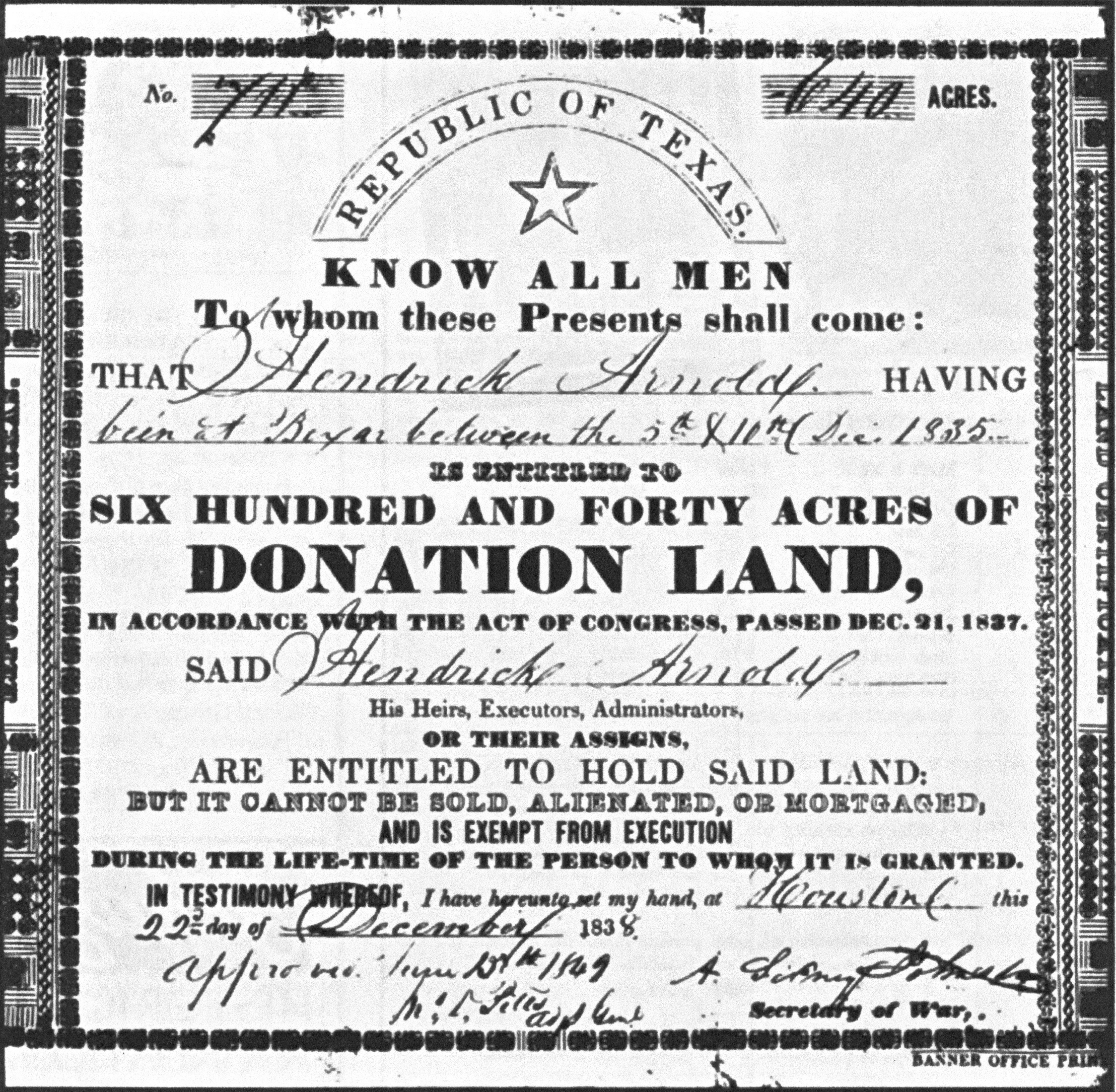

When Mexican forces under General Martin de Cos occupied Béxar, Hendrick, and his father-in-law Erastus “Deaf” Smith were out hunting buffalo. They encountered Stephen F. Austin’s camp of Texas volunteers headed to Béxar and volunteered to act as guides. Hendrick participated in the fight at Mission Concepción in December 1835 and was the guide for Ben Milam’s division during the capture of Béxar.7 He later served in Deaf Smith’s spy company at the battle of San Jacinto.8 Mary Ann Arnold may have lived on her father’s ranch, although, like many Bexar County ranchers, the family also had a house in San Antonio.9

Mary Ann’s first marriage was to John Brothers.

On June 25, 1848, Mary Ann married an Anglo-American, John Brothers, in Bexar County. By October 1850, she and her husband were living on a farm near Castroville in Medina County.10 Theirs was one of 41 families enumerated in and around Castroville that year. When Mary Ann married John Brothers, she was 15 years old. In 1848, it was common for girls to marry at the age of 12 or 13 and for 12-year-old boys to leave home.11

John Brothers was born about 1824 in Virginia and came to Texas on September 22, 1837, qualifying for a Second Class Head-right Certificate for 640-acres.12 He appeared on the muster rolls of David C. Cady’s ranging company, and on July 5, 1846, he was elected lieutenant of Cady’s Company in San Antonio for a six-month term.13 After his discharge from the ranging service in early 1847, he married Mary Ann Arnold in 1848 and settled on the farm near Castroville.

Within a few months after their marriage (in April or May of 1849), Mary Ann’s father, Hendrick Arnold, died in the cholera epidemic that swept through San Antonio.14 The epidemic lasted six weeks and killed more than 500 people15 out of a population of 3,480.16 John Brothers was called upon to act as administrator of Hendrick Arnold’s estate.17 He did not finish the task before he died sometime before September 1851.18

Since there were no surviving adult males in the family, Mary Ann became the administrator of her deceased husband’s estate. Mary Ann paid off the remaining debt on 369 acres and immediately sold 150 acres to two different persons.19 It appears that she retained title to her parent’s farm and ranch. She and John Brothers had no known children.

Mary Ann’s second marriage was to Tom Rife.

While Mary Ann and John Brothers were farming in Castroville, Thomas Rife was stationed about fifty miles away on the Leona River near Fort Inge.20 While in the ranging service, Thomas Rife occasionally visited San Antonio and received his mail there21, but no evidence has been found showing that he was acquainted with either John Brothers or his wife.

When US Army General Brooke dismissed all Texas rangers in Federal service in the fall of 1851,22, Rife had already left the ranging service after his year of fighting Indians. He and several other men from Wallace’s ranger company remained around Fort Inge in a settlement they called Inge, close to present-day Uvalde. These men included William W. Arnett,23 Ed Westfall, Sam Everett, Clem Howard, Cave Nelson, Howard/Henry Levering,24 Louis Oge, William Smith, and George Ware.

In the spring of 1852, Tom Rife and many of his friends were hired by Henry Skillman to drive or guard coaches for the new mail route.25 For the next eighteen months, Rife was almost always on the road and was only briefly in Bexar between trips. Despite this hectic schedule, he successfully courted Mary Ann Arnold, who also lived in Uvalde. The circumstances of their courtship and marriage are not known. The Chief Justice of Medina County (John Hoffman) performed the marriage ceremony on October 14, 1853. Bexar County issued the license, and two brothers, Charley D. Lytle and Samuel Lytle, William Smith, and Gideon Scallions witnessed the ceremony.26

Rife left his wife after two and a half months of marriage.

Three days after his marriage, Rife again left San Antonio with the mail train. He returned to San Antonio on December 10.27 According to Mary Ann, he then abandoned her after these short few months of marriage. When Rife left for the last time in December 1853, he may have felt that Mary Ann was trying to “fence him in.” Rife earned his living as a wagon master and a gunman and never seemed interested in either farming or ranching. Now he had to choose whether to settle down with his new wife to live as a rancher or to continue his life on the road. While many men would not have hesitated to settle down to a more stable life, this was the third chance for Rife to choose a career as a rancher or farmer. He had already rejected such a life twice before. Rife found a life-style he liked, and he may have decided to stick with it, even though it meant leaving his wife.

Mary Ann later said that Rife left her on December 27, just 73 days after their wedding, and never returned. She swore in her petition for divorce in 1860 that Rife abandoned her “voluntarily, without any cause or provocation, with the intention of wholly abandoning” her and “continued to abandon her for more than three years.” 28 Rife’s side of the story is not known, but it appears that he did not attempt reconciliation with his wife. Mary Ann did not want to divorce Tom Rife; she did so only a few months before she married her third and last husband in 1860.29 She and Tom had no children together.

Rife did not stay with the mail service very long after leaving his wife. The mail from Santa Fé that arrived in San Antonio on February 11, 1854, was, at first, attributed to Tom Rife but was, in the same edition, corrected and Capt. Bradford Daily was identified as the conductor.30

In 1853, everyone who could afford the trip was heading to California to look for gold.31 There were many men from Texas in California in the 1850s.32 Perhaps Rife conducted the mail coach to El Paso in late December of 1853 and proceeded from there to California. We know from Rife’s Application for a Pension for his Mexican War Service that he had “resided in Arizona, California, Nevada, and Texas.” 33 The San Antonio Daily Light edition of March 17, 1893, stated that Rife “celebrated St. Patrick’s day in 1854 in San Francisco.” 34 The only other evidence of Rife’s residence in California is an “Information Wanted” advertisement placed in the Sacramento Union in August 1857. It stated that Rife “came to California in 1853.” A letter addressed to R.F. Johnson, Campo Seco, Calaveras County, asked him to relieve the anxiety of his family and friends.35 Campo Seco was a promising mining community in 1856. Perhaps Mary Arnold Rife was preparing to begin divorce proceedings.

Mary Ann owned real property in her own right and did not look to Rife for help. The Marital Rights Act of 1840 allowed a woman to sell the property to support herself if her husband failed to do so.36 She sold 50 acres for $150 on March 2, 1855.37 She also applied to sell a building lot in San Antonio that she had inherited. She told the Court that Tom Rife had been in California for 12 months and left her with no means of support. The Court allowed her to keep the proceeds.38 Mary Ann continued to live in Uvalde County and was teaching school on the Sabinal River in the fall of 1857.39

By 1860, Rife had been absent for more than six years, and Mary Ann had given up hope that he would return. In a notice in the February 4, 1860 newspaper, a Sheriff’s writ ordered Thomas Rife to appear before the District Court of Bexar County on the first Monday in March to answer Mary Ann Rife’s suit for a decree of divorce and costs and relief generally. The notice was published in the San Antonio Ledger and Texan for four consecutive weeks as required by law, but Rife failed to appear for the divorce proceeding.40

Mary Ann’s third marriage was to William C. Adams.

Less than seven months after the divorce, on April 7, 1861, Mary Ann Rife married her third and last husband, William Carroll Adams, in Uvalde County.41 The 1860 census enumerated Adams as a stock raiser who lived at the former military post at Fort Inge. His parents moved from England to Corpus Christi in 1852 and entered the stock business. William Adams’ brother, Robert, served as a ranger in Wallace’s Company in 1850, and Mary Ann’s husband probably knew Rife, at least by reputation, before their marriage. Life as a single woman in 1860 was difficult and, although she had inherited her father’s ranch on the Medina River, she would not have wanted to be dependent on her few remaining relatives for help and support.

Mary Ann’s husband left for West Texas soon after their marriage to participate in the Confederate invasion of New Mexico.42 He returned the following year and enlisted in the Confederate army. After the Civil War, William Adams entered into a partnership with his brother Robert to raise sheep, continuing in that business until 1890. Adams became “one of the wealthiest and most prominent citizens of this Uvalde County.” 43

In 1870 Mary Ann and William were stock raisers in San Felipe, Kinney County44, but by 1880, like the families of most wealthy ranchers in the region, Mary Ann and her two daughters and two sons were living in San Antonio.45

It appears that William died before 1900; Mary Ann was living in San Antonio with two of her children at the time of the 1900 Census. In 1920, she was still living in San Antonio with her daughters, one of whom was widowed and the other single.46 Twice widowed, and once divorced, Mary Ann succeeded in marriage and motherhood. She died at age 92 in San Antonio on August 3, 1925, and is buried in Adartis Family Cemetery near Macdona, Texas.47

-

Harold Schoen, “The Free Negro in the Republic of Texas,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 40, (July, 1937), 95 ↩︎

-

Nolan Thompson, ”Arnold, Hendrick,” Handbook of Texas Online, (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/far15, accessed November 07, 2011), Published by the Texas State Historical Association. ↩︎

-

Schoen, “The Free Negro in the Republic of Texas,” 95 ↩︎

-

Schoen, “The Free Negro in the Republic of Texas,” 98 ↩︎

-

Thompson, ”Arnold, Hendrick,” Handbook of Texas Online ↩︎

-

Jesus De La Teja, San Antonio de Bexar: a community on New Spain’s Northern Frontier, (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 23 ↩︎

-

Stephen L. Hardin, Texian Iliad, A Military History of the Texas Revolution, 1835-1836, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994), 79 ↩︎

-

”Arnold, Hendrick”, Nolan Thompson, Handbook of Texas Online ↩︎

-

Rena Maverick Green, editor, Samuel Maverick, Texan: 1803-1870, A Collection of Letters, Journals and Memoirs, (San Antonio: Privately Published, 1952), 74; David McDonald, Jose Antonio Navarro, In search of the American Dream in Nineteenth-Century Texas, (Denton, TX: Texas State Historical Association, 2010), 126 ↩︎

-

John Brothers, Maryann Brothers, United States Seventh Census (1850), M432, Dwelling 38, Castroville, Medina County, Texas. ↩︎

-

Victor Bracht, Texas in 1848, (San Antonio: Naylor Printing Company, 1931), 72 ↩︎

-

John Brothers, Montgomery County Clerk Returns, August 1838, 2nd class certificate 78, GLO; John Brothers, Audited Republic claims, Texas Comptroller’s Office claims records. Archives and Information Services Division, Texas State Library and Archives Commission ↩︎

-

Henry W. Barton, Texas Volunteers In the Mexican War, (Waco, TX: Texian Press, 1970), 67 ↩︎

-

Schoen, “The Free Negro in the Republic of Texas”, 95 ↩︎

-

Pearson Newcomb, The Alamo City, (San Antonio: Standard Printing Company, 1926), 37 ↩︎

-

Vinton Lee James, Frontier and Pioneer Recollections, (San Antonio: Artes Graficas, 1938), 103 ↩︎

-

Bill of sale, Historical Records, County Clerks Office, Bexar County, Book I1, p. 572, San Antonio, TX. ↩︎

-

Schoen, “The Free Negro in the Republic of Texas”, 96 ↩︎

-

Bill of sale, Historical Records, County Clerks Office, Bexar County, Book M2, pp. 578-79; Bill Of sale, Historical Records, County Clerks Office, Bexar County, Book K2, p. 185 ↩︎

-

Walter Prescott Webb, The Texas Rangers, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1993), 141; Darren L. Ivey, The Texas Rangers: A Registry and History, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2010), 86 ↩︎

-

The Western Texan, (San Antonio), June 12, 1851; The Western Texan, (San Antonio), August 28, 1851 ↩︎

-

Webb, The Texas Rangers, 143; Texas State Gazette, (Austin) September 20, 1851 ↩︎

-

Thomas Tyree Smith, Fort Inge: Sharps, Spurs, and Sabers on the Texas Frontier, (Austin: Eakin Press, 1993), 57; Middle Rio Grand Development Council, Uvalde County, www.mrgdc.org/cog/cog_region/uvaldecounty.php#inge, accessed Aug 26, 2012. ↩︎

-

Fenley, Oldtimers, 213; Middle Rio Grand Development Council, Uvalde County. ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 28; Day, “Big Foot Wallace in Trans-Pecos Texas,” 73; San Antonio Light, February 23, 1887 ↩︎

-

Marriage Licenses, Bexar County Clerks Records, Book C, p. 118, (Oct. 14, 1853) ↩︎

-

San Antonio Ledger and Texan, December 15, 1853 ↩︎

-

The San Antonio Ledger and Texan, March 10, 1860 ↩︎

-

The San Antonio Ledger and Texan, March 10, 1860 ↩︎

-

The Western Texan (San Antonio), February 16, 1854 ↩︎

-

George Wythe Baylor, Into the Far, Wild Country: True Tales of the Old Southwest, (El Paso: Texas Western Press, The University of Texas at El Paso, 1996), 93 ↩︎

-

Baylor, Into the Far, Wild Country, 107-17 ↩︎

-

Declaration of Survivor for Pension, Records of the Bureau of Pensions, Mexican War Pension Application Files, 1887-1926, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, RG15, NARA ↩︎

-

San Antonio Daily Light, March 17, 1893 ↩︎

-

Sacramento Union, August 12-18, 1857 ↩︎

-

Brazos Courier, (Brazoria, TX), March 10, 1840; Bills of sale. Historical Records, County Clerks Office, Bexar County, Book 128, p. 169, Book O2, p. 144, and Book M2, p. 426 ↩︎

-

Bill of sale. Historical Records, County Clerks Office, Bexar County, Book M2, pp. 578-9 ↩︎

-

Mary Ann Rife vs. Thomas Rife. Bexar County Probate minutes (1851-1857), Vol. C, p. 439, Reel 1019295, ARIS-TSLAC ↩︎

-

Smith, Fort Inge: Sharps, Spurs, and Sabers on the Texas Frontier, 116 ↩︎

-

Thirty seventh District Court, Bexar County. Civil Minutes, (1860-1868), Vol. F, p. 4, Microfilm Reel 1019987, San Antonio; Court Record of District Court, Clerk of District Court, Bexar County, (Fall term, 1860), Vol. F, p. 5, San Antonio ↩︎

-

William C. Adams (April 7, 1861), Texas Marriages, 1837-1973, https://familysearch.org/pal:MM9.1.1FXSJ-4NB: accessed 19 Oct 2012 ↩︎

-

The Daily Ledger and Texan, (San Antonio), April 2, 1861; Clayton W. Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier: Fort Stockton and the Trans-Pecos, 1861-1895, (College Station, TX: Texas A & M University Press, 1982), 21-2 ↩︎

-

The Daily Ledger and Texan, (San Antonio), April 2, 1861; George Wythe Baylor, Into the Far, Wild Country, 213 ↩︎

-

Mary A. Adams, United States Ninth Census (1870), M593, San Felipe, Kinney County, Texas, Role 1594. ↩︎

-

Mary E. Adams, United States Tenth Census (1880), T9, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas, Role 1291. ↩︎

-

Mary A. Adams, United States Twelfth Census (1900), T623, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas, Role 1611, 1612. ↩︎

-

Mary Ann Adams (Aug 3, 1925), Certificate of Death, Department of Health-Bureau of Vital Statistics, State of Texas. ↩︎