Pecos County, 1870–1873

Captain Rife remained in West Texas until 1872.

By 1870 Tom Rife was 47 years old and had worked for 18 years in the Trans-Pecos region of West Texas. He was known as Captain Rife because of his work as a conductor of stagecoaches.1 In that capacity, he was responsible for the stagecoach and its passengers, the mail it carried, and the men who drove and protected it. He returned to San Antonio shortly after the war. Nevertheless, by 1870, he was again west of the Pecos River in what later became Pecos County.

By July 1866, mail coaches resumed operations between San Antonio and El Paso.2 Despite frequent attacks by Indians, the mail stations were repaired and stocked with livestock3, and by the following spring, three mail wagons were stopping at Fort Stockton every week.4

The road between San Antonio and El Paso, already a well-marked highway, was improved.5 In 1868 a bridge was constructed over the Pecos River6 in a location that previously was crossed on a skiff when the water was high.7 Two years later, the bridge was replaced by a new pontoon bridge that quickly became the main crossing.8 Also, once a week, the mail coach traveled from Fort Stockton and Fort Davis to Presidio del Norte on the Rio Grande.9

Thomas Rife was qualified to hold public office.

Rife surrendered to Federal authorities in San Antonio in 1865, as was required of those who served in the Civil War as Confederates.10 He took a loyalty oath before he was paroled.11 The general amnesty required only a simple oath of loyalty to the US Constitution and its laws.12 Two years later, a stricter oath, called the “ironclad oath” was introduced.13 Anyone who could or would not take this second oath was prevented from serving as a juror or acting as a state or local official. The oath stated that he had not given “aid, countenance, counsel or encouragement” to the Confederacy.

In the election of 1869, all candidates who had won their election but who could not take the ironclad oath were disqualified from taking office.14 The requirement to swear the ironclad oath would have prevented Rife from standing for election in a county election if, as a mail carrier, he had previously taken an oath to the US Constitution.15 In practice, before the Civil War, only postmasters and mail contractors were required to take an oath to the US Constitution.16 As a result, Rife was qualified to hold public office after the Civil War.17

Local boards were appointed to administer the loyalty oath and to register voters.18 In 1869, the Texas voter registration boards were mostly partisans of the radical Republican candidate for governor, E. J. Davis.19 However, the restrictions placed on former Confederates may have been relaxed in the Trans-Pecos region because the Republican Party considered Texas west of the Colorado River to have been loyal to the Union.20

Stagecoach drivers and guards, and especially those of the mail service, were seen by the Federal government as trustworthy.21 Rife was well known in West Texas, and law-abiding citizens of the region welcomed him22 when he resumed his work as a mail carrier after the war.23 Rife was acquainted with many of the influential men in West Texas, and these contacts and old friends would have been important to Rife and surely influenced his decision to return there.

A generation later in 1891, affidavits by Rife and George Giddings described the exact location of San Martin Springs, of vital importance in determining the boundary line between El Paso, Jeff Davis and Reeves Counties.24 In Rife’s mail service days, it was known as Barrilla Spring.

West Texas forts were re-occupied by the US Army beginning in 1867.

Immediately after the war, the US military was preoccupied with establishing an occupying force in the settled regions of Texas and along the Rio Grande and did not begin to return to the Trans-Pecos until after the French had left Mexico in June 1867.25 After this time, the Army responded to Indian depredations by gradually increasing its presence in the Trans-Pecos region.26

The US Government renounced the Quaker Peace policy that previously governed its relationship with indigenous peoples and became more aggressive in its treatment of Indians. Many Indians were forcibly confined to reservations.27 The Texas Legislature abolished the widely distrusted State Police28 and reinstated the ranger service29 to reduce tensions between ex-Confederates and State authorities.30

Beginning in January 1869, Forts Stockton, Davis, Quitman, Clark, McKavett, Concho, and Duncan were garrisoned by Black infantry and cavalry companies, known as the Buffalo soldiers. Buffalo soldiers were African American soldiers who mainly served on the Western frontier following the American Civil War. In 1866, six all-Black cavalry and infantry regiments were created after Congress passed the Army Organization Act. Their main tasks were to help control the Native Americans of the Plains, capture cattle rustlers and thieves and protect settlers, stagecoaches, wagon trains, and railroad crews along the Western front.

Black troops had occupied fort Bliss since June 1865.31 It appears that the transition from garrisons of Anglo-European soldiers to Black troops went smoothly in West Texas. State and military officials in east Texas, where the white population would not accept Black troops, took notice of this. In February 1869, some Republican lawmakers wanted to divide the state of Texas into two or three states32 in order to separate unrepentant Confederates in the east from those in West Texas whom they considered loyal to the Union. The area to the west of the Colorado River was considered to be safe for freed slaves and the Black soldiers and could be granted self-government without fear of adverse consequences.33

The Legislature created Pecos County in 1870.

The Republican-led Texas Legislature appointed three commissioners to hold an election to form Presidio County in the Big Bend area of the Rio Grande.34 In 1871, Pecos County was created. A board to organize the new county was to be appointed on the first Monday in May of that year, but the members of the board were not appointed until May 12. This delay may have been why the attempt to organize the county failed.35

Peter Gallagher, a merchant in both Fort Stockton36 and San Antonio, was instrumental in forming at least two county governments in the Trans-Pecos region. He served on the Board of Commissioners for Presidio County in 1870.37 Choosing the county seat was of paramount importance to landowners and merchants. They often owned real estate and had mercantile businesses to protect.

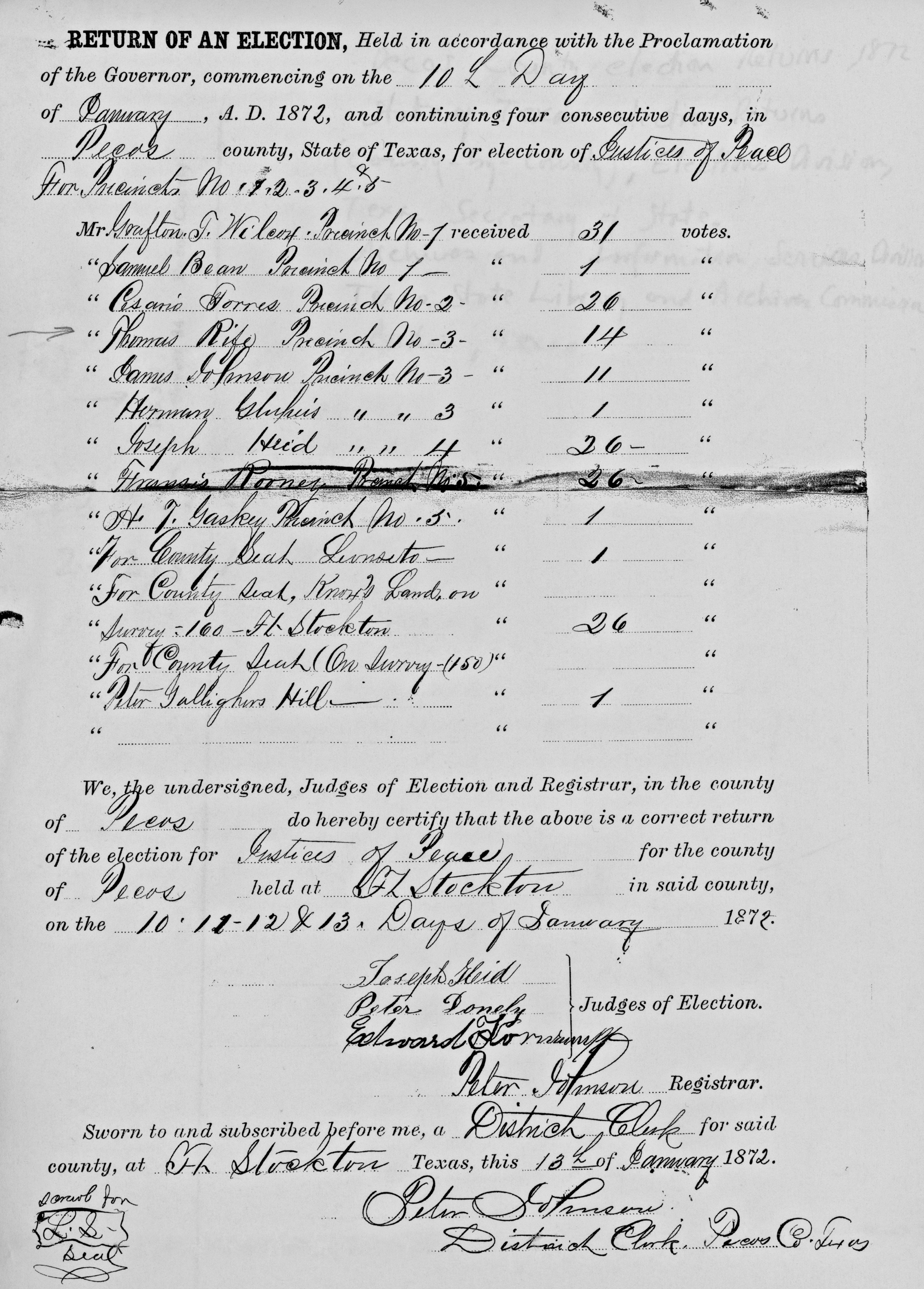

Thomas Rife was elected Justice of the Peace in 1872.

On January 13, 1872, Tom Rife was elected a Justice of a Peace in Pecos County at Fort Stockton.38 Rife won the election for Precinct No. 3 with 14 votes to 11 and 1 in a three-way race and was commissioned on February 29.39 The third precinct was in far eastern Pecos County on the Pecos River. Perhaps Rife was working there as a mail station manager.40 The year 1872 was also a national election year. During the November election (which ran for four days), Horace Greeley, the Democratic and Liberal Republican candidate, received 25 votes for President and U.S. Grant, the Radical Republican candidate, received 18 votes. There were only 45 registered voters in the new county, described as “26 whites, 10 Mexicans, and nine colored men.” 40”

There is no evidence that the elected county officials ever met, and this election did not result in the seating of a county court of commissioners. Ballot stuffing and vote-buying was the order of the day in most county elections of this kind, and the election in Presidio County proved to be no exception.41 In November 1872, the returns of El Paso and Presidio counties were thrown out “on account of mob violence, intimidation and undue influence” 42 The Secretary of State may also have decided that the Pecos County vote was not valid because the county did not have a sufficient number of registered voters to entitle them to organize a county government.43

Rife might not have served as a Justice of the Peace after his election as the records are unclear. Three years later, in March 1875, a special election was held in Pecos County to fill vacancies that included District Clerk, Sheriff, Treasurer, County Surveyor, Hide Inspector, and all five Justices of the Peace.44 Another general election was held the next year and elected a new set of officials. In January 1876, precinct boundaries were again delineated.45 The earliest records in the Pecos County Courthouse in Fort Stockton date from 1875.

Thomas Rife and his wife left Pecos County in 1873.

It is unclear what Rife was doing in Pecos County in January 1872 and why he stood for election as a Justice of the Peace. At that time, he and his wife lived in or near Fort Stockton.46 Eligible to serve as a county official, the voter registrars, who also supervised the elections, accepted him.47 With only 45 registered voters in the proposed county, the list of possible candidates would have been short. In 1870, US military authorities stipulated that each county had to have five Justices of the Peace to constitute the police court. Each Justice of the Peace had to post a bond of $500 to the county police court.48 The requirement to post a bond of such a large amount further narrowed the field of prospective candidates.

Soon after the election, Rife left Pecos County. He may have known that the era of cross-country stagecoaches was over; the heroic period of Texas history, and his role in it, was fast drawing to a close. The Southern Pacific Railroad from San Diego, California, reached El Paso in May 1881. The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fé Railroad reached El Paso from the east in June 1881. The Texas & Pacific Railroad followed in January 1883. The railroads led to a large shift in the population; many workers of all races suffered from downward mobility after the closing of the frontier (i.e., after the coming of the railroads).49

Freighters who hauled merchandise between San Antonio and the Rio Grande Valley disappeared when the Southern Pacific Railroad reached Eagle Pass in 1878, and the Great Northern Railroad reached Laredo in 1883.50 In 1877, the first train of the Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio route entered San Antonio and its bell, reaching the ears of the men who drove stages and who freighted goods, tolled the demise of long-distance mail coaches and freight trains. A second railroad, the International and Great Northern Railroad reached San Antonio from Houston in 1880. In 1883 and 1885, routes were opened to Corpus Christi and Kerrville, respectively51 In 1886, Pap Howard reportedly drove the last stage out of San Antonio to San Angelo. According to a newspaper reporter, “it was with tears in their eyes that many of the city’s intrepid pioneers watched him disappear into the distance.” 52 They realized that the days of the cross-country stagecoaches and freight trains pulled by mules had come to an end.

-

George G. Smith, The Life and Times of George Foster Pierce, D.D., LL.D., (Sparta, GA: Hancock Publishing Co., 1888), 381 ↩︎

-

Thonhoff, San Antonio Stage Lines 1847-1881, fig. 25 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 68 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 91 ↩︎

-

Richardson, Beyond the Mississippi, 234 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 97 ↩︎

-

Richardson, Beyond the Mississippi, 233 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 126; August Santleben, A Texas Pioneer, (New York and Washington: The Neale Publishing Co, 1910), 145 ↩︎

-

Thonhoff, San Antonio Stage Lines 1847-1881, fig. 30; Nunn, Texas Under The Carpetbaggers, 157 ↩︎

-

Thomas Rife Record, 36th Texas Cavalry Regiment, Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of Texas, M323, Roll 175, Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served During the Civil War, RG109, National Archives and Records Administration ↩︎

-

Florence Johnson Scott, Old Rough and Ready on the Rio Grande, (Waco, TX: Texian Press, 1969), 175; United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies, Series 1-Volume 1: 578-80 ↩︎

-

David McDonald, Jose Antonio Navarro, In search of the American Dream in Nineteenth-Century Texas, (Denton, TX: Texas State Historical Association, 2010), 258 ↩︎

-

Richter, The Army in Texas During Reconstruction, 99; Nunn, Texas Under The Carpetbaggers, 21 ↩︎

-

Richter, The Army in Texas During Reconstruction, 185; McDonald, Jose Antonio Navarro, 261-2 ↩︎

-

Nunn, Texas Under The Carpetbaggers, 21 ↩︎

-

Anonymous, Special Presidential Pardons for Confederate Soldiers: A listing of former Confederate soldiers requesting full pardon from President Andrew Johnson, (Signal Mountain, TN: Mountain Press, 1999) ↩︎

-

James Farber, Texas, C.S.A.: A Spotlight on Disaster, (New York & Texas: The Jackson Co., 1947), 247 ↩︎

-

Richter, The Army in Texas During Reconstruction, 48 ↩︎

-

Nunn, Texas Under The Carpetbaggers, 16 ↩︎

-

Richter, The Army in Texas During Reconstruction, 165 ↩︎

-

Nancy Lee Hammons, (thesis) A History of El Paso County, Texas, to 1900,(El Paso: University of Texas Press, 1983) 54 ↩︎

-

N.A. Jennings, A Texas Ranger, (Dallas: Turner Co., 1930), 54; King, Texas 1874, 46, 74; Hammons, A History of El Paso County, Texas,to 1900, 55 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Light, February 23, 1887 ↩︎

-

El Paso International Daily News, May 23, 1891 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 81 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 82, 90, 146 ↩︎

-

Raht, Romance of Davis Mountains and Big Bend Country, A History, 196 ↩︎

-

Hans Peter Mareus Neilsen, The Laws of Texas, 1822-1897, Vol. 7, 1898, http://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth6732: accessed May 23, 2011 ↩︎

-

Hammons, A History of El Paso County, Texas, to 1900, 55 ↩︎

-

Richter, The Army in Texas During Reconstruction, 193 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 58 ↩︎

-

Richter, The Army in Texas During Reconstruction, 159 ↩︎

-

Richter, The Army in Texas During Reconstruction, 1657 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 127 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 128; Daggett, editor, Pecos County History, 106 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 92 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 127 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 154; Elected and Appointed Local Officers, (1870-1878), Reel 5, Texas Secretary of State election registers (a.k.a. appointment registers), Archives and Information Services and Texas State Library and Archives Commission; Marsha Lea Daggett, ed., Pecos County History, (Canyon Texas Staked Plaines Press, 1984) 107 ↩︎

-

Pecos County Election Returns, 1872, State of Texas election returns (county-by-county), Elections Division, Texas Secretary of State. ARIS-TSLAC. ↩︎

-

Pecos County Election Returns, 1872, State of Texas election returns (county-by-county), Elections Division, Texas Secretary of State. ARIS-TSLAC. ↩︎

-

Frank S. Gray, Pioneering in Southwest Texas: True Stories of Early Day Experiences in Edwards and Adjoining Counties, (Austin: The Steck Company, 1949), 56-8 ↩︎

-

Nunn, Texas Under The Carpetbaggers, 110 ↩︎

-

Nunn Texas Under The Carpetbaggers, 113 ↩︎

-

State of Texas election returns (county-by-county), ARIS-TSLAC ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier, 200 ↩︎

-

Francis R. Pryor, “Tom Rife, An 1890’s Custodian of the Alamo”, STIRPES 35, No. 3, (September 1995), 46; Mexican War pension records, copies in Thomas Rife File, Daughters of the Republic of Texas Library at the Alamo, San Antonio, Texas ↩︎

-

Eligibility for Public Office, Texas Constitution, Election Code, Title 9, Chapter 141, Subchapter A; Nunn, Texas Under The Carpetbaggers, 17 ↩︎

-

Nunn, Texas Under The Carpetbaggers, 26 ↩︎

-

Montejano, Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 94 ↩︎

-

William Corner, comp. and ed., San Antonio De Bexar: A Guide and History, (1890, repr. (San Antonio, TX: Graphics Arts, 1977), 166; Montejano, Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 92-4 ↩︎

-

Corner, San Antonio De Bexar: A Guide and History, 133 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Express, May 28,1939 ↩︎