The Republic of Texas

Nathaniel and Samuel Chambliss influenced Thomas Rife to go to Texas.

The westward movement of planters continued into the next generation when several Rife, Chambliss, Wade, and Sibley descendants moved to Texas to the agricultural limits of the Cotton Kingdom.1 Two uncles of Thomas Rife (Nathaniel and Samuel Chambliss) and one aunt (Martha Bell) went to Texas. Another died in Texas in 1864 as a refugee during the Civil War. At least four children of Peter Chambliss moved to Texas. Except for Nathaniel Chambliss, these families moved to Texas after the Civil War when there was a general movement of impoverished planters from the Old South.2 Like most settlers of this period, they went to Texas as economic refugees and land speculators.

The fifth child of Peter Chambliss was Nathaniel Chambliss, born in 1802 in South Carolina. Samuel Lee Chambliss was the tenth child in the family. He was a volunteer soldier in the Texas war for independence in 1836. After the Texas war, he lived in Louisiana and Mississippi for a time then returned to Texas in 1867 and died in Navarro County, Texas, in 1876. His experience in Texas undoubtedly influenced his older brother Nathaniel and his young nephew, Thomas Rife, as well as other men, to move to Texas.

Samuel Chambliss joined the fight for Texas independence.

After the Texas revolution began in 1836, hundreds of young men from the American states rushed to Texas to join the fight. American volunteers formed the majority of the Texas army3, and probably only twenty percent of the men of the Texas army that fought at San Jacinto were residents of Texas. The other soldiers were young men who came to Texas to “fight for their country.”4 One of these men was Tom Rife’s uncle, Samuel Lee Chambliss.

On November 15, 1835, Samuel Chambliss helped to raise and equip a volunteer militia company in Carroll Parish to fight with Texas Federalists against Mexican Centralists led by General Santa Anna. Samuel and his friends in Carroll Parish raised over $5,000 to equip the company for the campaign. The company of 124 men traveled overland to Washington-on-the-Brazos, soon to be the seat of government of the new Republic of Texas. After the company arrived at Washington-on-the-Brazos, its original commander returned to Louisiana, and the company was reorganized with Samuel Chambliss in command.5

In February 1836, Samuel’s company, along with that of Capt. Samuel Williams was sent in pursuit of a band of Native Americans who were raiding American settlements east of the Trinity River. The Indians were overtaken near a place called Comanche Peak (in present-day Johnson County) and escaped after a running fight over several miles.

During the fight, Samuel was wounded in his right arm. His companions removed the arrowhead or barb, but he could not use his arm and could not continue the pursuit.6 Chambliss’ company was disbanded soon afterward for a “want of provisions and let loose in order to scatter and get subsistence.”7 Chambliss stated that “In April 1836, the grass gave out, the horses became unfit for such service and I disbanded the company”.8 Samuel then went to Gross’ (or Groce’s) plantation on the Brazos River to offer his services to Sam Houston, commander of the Texas army. Chambliss was assigned to deliver General Houston’s mail and dispatches to US General Gaines at Fort Jessup near present-day Many, Louisiana.9

While he was at Fort Jessup, a musket ball was removed from Chambliss’ thigh. He had been wounded in a fight on the Upper Colorado River a month or two before. He was then ordered by General Houston to go to Vicksburg, Mississippi, to deliver messages and to raise a battalion of cavalry. Subsequently, Houston asked Chambliss to encourage men to come to Texas as settlers. Towards that end, in the late summer and fall of 1836, Chambliss delivered speeches before gatherings in Jefferson, Warren, and Claiborne Counties in Mississippi to encourage farmers to move to Texas.10

Samuel Chambliss returned to the United States after the Texas Revolution.

Samuel was furloughed from the Texas army at Nacogdoches in October 183611, along with the majority of the army.12 He received a discharge paper that he lost in 1862 or 1863 when, according to Chambliss, “our house in Louisiana was broken into by force by the Federal Army and said Discharge and letters with my library were destroyed.”13 In the fall of 1836, Samuel Chambliss returned to Carroll Parish, where he recovered from his wounds.14 He then returned to Jefferson County, Mississippi, where he may have inherited land. He and Jane T. Scott had married in 1833. They settled down to raise a family and to operate a plantation, growing cotton with ten slave laborers.15 By 1860 he owned 116 slaves and was living in Carroll Parish.16

Samuel told war stories to friends and family upon his return home. His audience included his older brother, Nathaniel, and his nephew, Tom Rife. Samuel must have extolled the agricultural potential of Washington County, Texas, an area with which he was familiar. The availability of good, cheap land influenced his brother Nathaniel to move to Texas in 1838. Nathaniel had already outlived two wives and may have been seeking a healthier climate. Like many other farmers, he may have been escaping financial trouble caused by the Panic of 1837. Young Tom, who never wanted to be a farmer, may have been attracted by the prospect of war and Indian fights.

Farmers from the Old South immigrated to Texas after 1836.

Three principal routes led to Texas in 1838. Perhaps the most common was by ship from New Orleans via the Gulf of Mexico to Galveston or a landing on the Gulf coast.17 The usual overland route was by steamer up the Red River to Natchitoches and then along the Old Spanish or San Antonio Road (El Camino Real) through to Nacogdoches in Texas.18 Settlers traveling this road passed through the mostly uninhabited Neutral Ground in western Louisiana crossed the Sabine River at Gain’s Ferry and passed through the villages of San Augustine and Nacogdoches. There they bought corn from already established farmers.19 The best route for wagons was said to be through San Augustine, Nacogdoches, Washington-on-the-Brazos, and Columbus and then on to the Lavaca River and Spring Hill.20 Samuel Chambliss was familiar with the Old Spanish Road, and he probably recommended that route to Nathaniel as the safest and easiest way to reach Texas. A third, less commonly used route, the Opelousas Road, went overland through southwestern Louisiana.21

Large numbers of emigrants traveled overland to Texas after the battle of San Jacinto in ox-carts, in wagons, on foot, and horseback. Many were encouraged to immigrate to Texas between 1837 and 1841, with the promise of a 640-acre head-right. Before the American Revolution, some British colonies on the Atlantic coast offered a head-right of either fifty or 100 acres, either to the immigrant himself or the immigrant’s sponsor.22 After the American Revolution, all land west of the thirteen original states became the property of the Federal government, which did not continue the practice of giving a head-right to new arrivals to its territories. Most prospective Texas settlers came from states or territories that offered settlers no free land other than soldier’s bounties.23

A growing number of farmers in the southern states were in search of better, cheaper land24, and the Texas river bottomland was known to be fertile and suitable for cotton.25 Men such as Samuel Chambliss, who had traveled to Texas during the Texas War for Independence, spoke impressively of the agricultural potential of the Republic. What attracted their attention were the board river valleys of the Sabine, Neches, Trinity, Brazos, and the Colorado Rivers.26

The Texas Congress levied few taxes and financed government operations by issuing government paper and land certificates.27 As a result, land certificates were cheap and plentiful.28 A land certificate, whether it was a soldier’s scrip or a head-right, gave the holder the right to claim a given amount of vacant land anywhere in the public domain. Since the high cost of locating, surveying, and patenting the land had to be paid by the prospective settler before he could receive the title,29 many new emigrants found it advantageous to rent or to lease land from speculators rather than making a land claim based a land certificate.30

Nathaniel Chambliss settled in Washington County in 1838.

It is unclear when Thomas Rife came to Texas. He may have accompanied his uncle, Nathaniel Chambliss, when Nathaniel moved from Carroll Parish to Washington County, Texas, in 1838.31 There was a great deal of migration to Texas immediately after becoming a republic, although the pace of new arrivals slowed following the Panic of 1837.32 The Panic was followed by a lengthy recession that affected Texas as well as the United States, and cotton prices fell by 50%, bankrupting many businesses, including planters.

It was said that the same qualities of daring, bravery, reckless abandon, and heavy self-assertiveness that motivated a man to go to Texas also fitted him to conquer the wilderness.33 According to Noah Smithwick, who lived in San Felipe during this period, many of the men who came to Texas during the Republic were fleeing their past.34 Some were bankrupts, murderers, or adulterers who came to Texas to escape the reach of the law. In the United States, bankrupt individuals were sent to jail, while in Texas, they were safe from the United States criminal and bankruptcy law. Most people in Louisiana and elsewhere assumed that immigrants to Texas during this period were either villains or desperate men.35

Many of the young men who came to Texas were simply looking for adventure and excitement.36 While young Thomas Rife fit this description, Nathaniel Chambliss did not. He was an older man accustomed to owning and managing property. He was married and well established in his community.37 He was a planter who was drawn to the opportunities presented by the opening of Texas to American settlement. The land in Washington County that bordered the creeks was considered among the best agricultural land in Texas38, and that is where Nathanial Chambliss settled.

Thomas Rife arrived in east Texas before 1842.

Before leaving Louisiana, Nathaniel, on May 13, 1838, married his third wife, Caroline Hale, who was twenty years his junior.39 Between June 1838 and May 23, 1839, Nathaniel and his entourage arrived in Washington County.40 William Lytle, a blacksmith, arrived in Washington-on-the-Brazos from Tennessee with his wife and son Samuel on December 15, 183841 and eleven-year-old Samuel Lytle met Tom Rife in 1842.42 Their paths crossed many times throughout their long lives in southwest Texas.

Nathaniel probably rented land for his first two years in Texas. New arrivals to Texas after March 2, 1836, rented land because “original Texians” (those who resided in the Republic on the date of the Declaration of Independence) had a preference in the matter of locating their head-rights.43 On February 11, 1840, Nathaniel bought 840 acres for the sum of $2,000 from John Lott, an early settler.44 This land, on New Years Creek in Washington County, was part of the Mexican land grant of Samuel R. Miller.45 Nathaniel paid $2.38 per acre for what must have been a working farm. It was in the Brazos watershed and was considered some of the most fertile agricultural land in the State.46 The farm was a mix of undeveloped woodland and prairie with a small cleared field and a cabin.

Nathaniel Chambliss was a man of means.

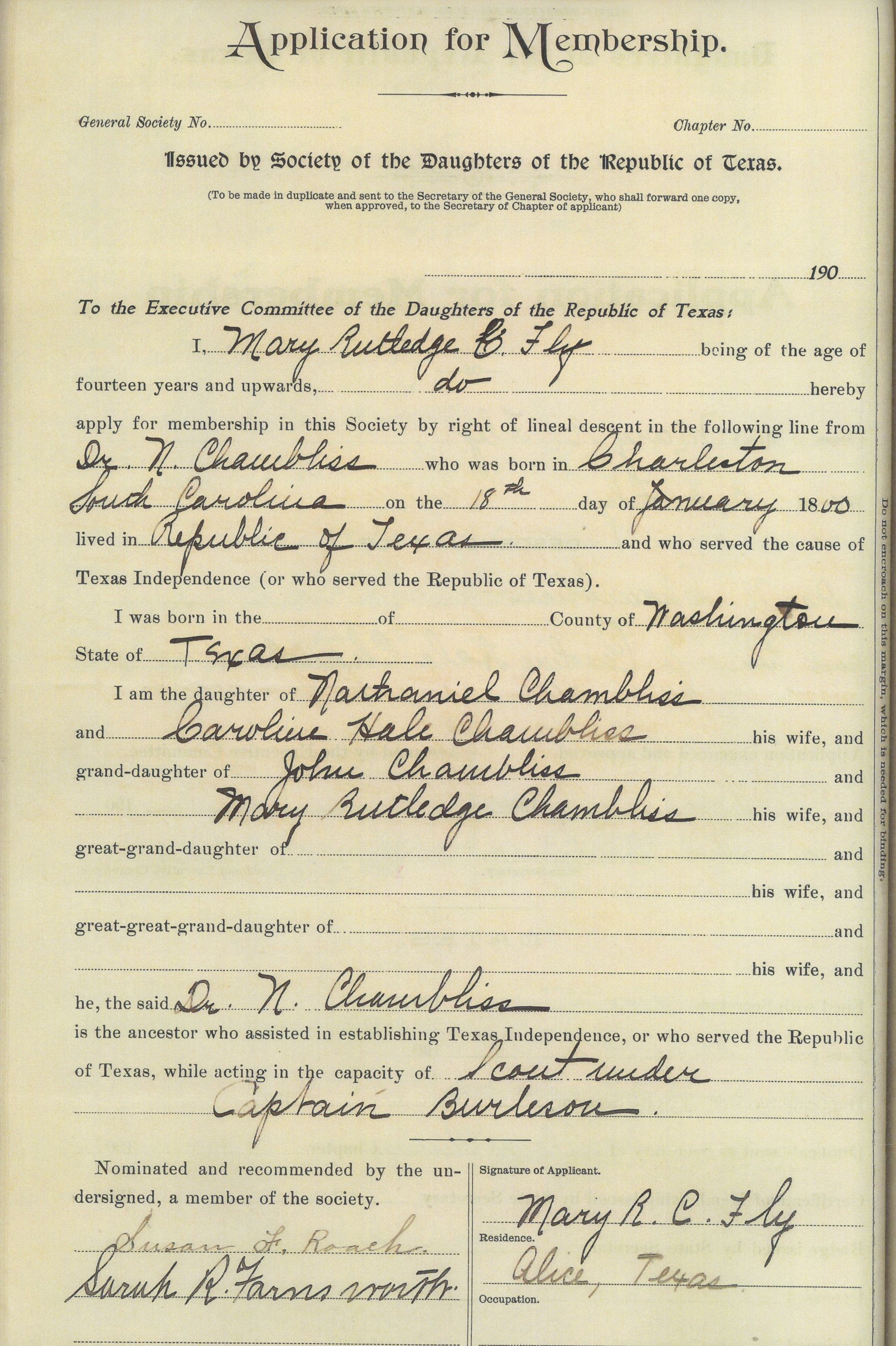

Nathaniel and Caroline’s new home was two miles from Chappell Hill and six miles from both Washington and Independence.47 The village of Washington was, at that time, the seat of government of the Republic. His oldest daughter, Mary Rutledge, stated that she often rode behind her father in 1843 into Washington on horseback.48 Chambliss was a man who shouldered his responsibilities to his neighbors and served wherever he was needed to maintain a civil society in Texas.49 Mary, in 1919, wrote, “Our home was the rendezvous of many of our great men. Among the number were Houston, Rusk, Burleson, Wharton, Lamar and others well known at that time…”.50 As time would tell, Nathaniel was not a successful land speculator.

A provision of an act of the Congress of the Republic of Texas on January 4, 1839, extended donations of land to Late Emigrants (emigrants who arrived in Texas after the establishment of the Republic). Nathaniel Chambliss was granted, on May 23, 1839, a Class 3 Conditional Certificate for 640-acres of vacant land as the head of a household who arrived in Texas between October 1, 1837, but before January 1, 1840.51 He received Certificate No. 104.52

The tax rolls of 1840 suggest that Nathaniel was a man of means. He owned a carriage, a clock, and four slaves, all taxable luxuries at that time.53 Although the records are incomplete, tax rolls from 1840 show only forty carriages in the Republic, with twenty-two owned by individuals in Washington County.54 Chambliss paid a tax of $4 for his carriage, as well as the tax on four slaves.55

The war with Mexico began again in 1842.

In March of 1842, the Republic of Texas was again at war with Mexico.56 Texas President Sam Houston, despite the opposition of Congress, sent a military expedition to Santa Fé in Mexican-held New Mexico.57 Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna responded by sending a similar expedition to west Texas.58 On March 5-7, 700 Mexican soldiers under General Rafael Vásquez occupied San Antonio.59 In response to this invasion, Nathaniel Chambliss joined Capt. Samuel Bogart’s Company of the Southwestern Army of the Republic of Texas, 1st Regiment.60

On June 3, 1843, Moses Park was given a Power-of-Attorney to act as Nathaniel’s agent at the county seat of Mt. Vernon during Nathaniel’s absence from the Republic.61 Many prudent Texans left the region west of the Colorado River during this period. East Texas, including Washington County, was considered quite safe from any Mexican invasion force.62 Nathaniel may have returned to the neighborhood of Lake Providence to manage his affairs there since he patented land at the Ouachita Land Office as late as 1846, ten years after he moved to Texas.

Nathaniel Chambliss served as a trustee for his church and road overseer for the precinct where he lived.63 Nathaniel was a Methodist.64 and a trustee of the Cedar Creek Methodist Church. He was instrumental in creating the Methodist camp at Cedar Creek.65 The Second Great Awakening was in full swing in Texas by the 1840s, and highly emotional camp meetings were a regular feature of religious life on the frontier.66 Camp meetings met the social, as well as the religious needs of the isolated population, and were a convenient time for many people to be baptized and to visit distant neighbors.67 Preachers riding a circuit helped alleviate the shortage of resident pastors. Methodist and Baptist churches proliferated and were the focus of community life in the first half of the 19th Century.68

A bill enacted in 1841 laid out procedures to swear, with witnesses, to the continued residence of conditional land certificate holders to convert conditional certificates to unconditional certificates.69 Nathaniel’s Class 3 Certificate granted on May 23, 1838, required a three-year residence in Texas before it could be deemed unconditional. Nathaniel Chambliss completed the residence requirement and was issued an Unconditional Certificate in Washington County for 640 acres of land on February 26, 1849.70

Nathaniel Chambliss moved his family to Lavaca County.

Before 1850 Nathaniel Chambliss sold his farm in Washington County and moved to Lavaca County.71 He continued to serve in public office and prospered after his move to Lavaca County. In 1851 he received his long-delayed pay for military service during the Vásquez campaign of 184272, and in the spring of 1853, he registered a cattle brand and purchased a cotton gin.73 The following year he used his head-right certificate to patent 640 acres in Erath County 250 miles from his home.74 He probably never visited the land75, and it was sold at auction after his death.76

In August 1852, Nathaniel was elected to the Lavaca County Commissioners Court, where the first duty was to settle a dispute involving an election to pick the location of the county seat.77 Such elections were always hard-fought and often fraudulent.78 The presence of a courthouse usually guaranteed that a town would thrive at the expense of other nearby villages in the same county.79 Although the town of Hallettsville received the majority of votes cast, the people of Petersburg (a village in the Zumwalt Settlement that no longer exists) contested the election. Eventually, an armed posse was sent to Petersberg to secure the county records for the town of Hallettsville.80

A June 15, 1858 newspaper story about Lavaca County mentioned that Dr. Chambliss planted a field of twenty-acres in a variety of maize called Peabody Corn. The article asserted that this variety would yield at least 100 bushels of corn to the acre.81 It appears that Nathaniel was an innovative farmer willing to risk planting new crop varieties. This article called him “Doctor Chambliss,” a title he used in later life. The title was honorary, and there is no evidence that he received formal training in or even practiced medicine.82

In the Census of 1860, only Nathaniel, his wife, and their 16-year-old son remained at home.83 His two daughters married in 1856 and 1858.84 While Nathaniel, from all appearances, was a wealthy man, he was, in reality, deeply in debt. On May 16, 1859, his financial condition worsened. He was forced to mortgage 751 acres, all cotton produced on the land, and the fifteen slaves who worked the fields to Tarleton, Whiting, and Tullis, a New Orleans firm of cotton buyers or factors.85 Two years later, on March 19, 1861, he took out a second mortgage on one of these tracts (320 acres and four slaves) from Josiah Dowling, a resident, and acquaintance of Chambliss, for $2,218.47.86 The coming Civil War bankrupted most Southern planters, and Nathaniel was unable to pay back the money he had borrowed.

-

Andrew Forest Muir, Editor, Texas in 1837: An Anonymous, Contemporary Narrative, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1958), 98 ↩︎

-

Steven D. Smith, A Good Home for a Poor Man: Fork Polk and Vernon Parish, 1800-1940, (Columbia: University of South Carolina, 1999), 81-2 ↩︎

-

Muir, Texas in 1837, 135 ↩︎

-

J. Frank Dobie, The Flavor of Texas,* (Dallas: Dealey and Lowe, 1936), 94 ↩︎

-

Samuel L. Chambliss, Republic Pension Files, Republic Pension Records, Texas Comptroller’s Office claims records. ARIS-TSLAC Division, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Austin, TX, 364, 384 ↩︎

-

Samuel L. Chambliss, Republic Donation Voucher, file # 1319, Archives and Records Program, Texas General Land Office, Austin, TX. ↩︎

-

Samuel L. Chambliss, Republic Pension Files, Republic Pension Records, Texas Comptroller’s Office claims records. ARIS-TSLAC, 364 ↩︎

-

Samuel L. Chambliss, Republic Donation Voucher, file # 1319, GLO ↩︎

-

David McDonald, Jose Antonio Navarro, In search of the American Dream in Nineteenth-Century Texas, (Denton, TX: Texas State Historical Association, 2010), 52 ↩︎

-

Samuel L. Chambliss, Republic Donation Voucher, file # 1319, GLO ↩︎

-

Samuel L. Chambliss, Republic Pension Files, Republic Pension Records, Texas Comptroller’s Office claims records. ARIS-TSLAC, 377 ↩︎

-

Mrs. Anna J. Hardwicker Pennybacker, A History of Texas for Schools, (Austin: Mrs. Percy V. Pennybacker, Publisher, 1912), 212 ↩︎

-

Samuel L. Chambliss, Republic Pension Files, Republic Pension Records, Texas Comptroller’s Office claims records. ARIS-TSLAC, 374; Samuel L. Chambliss, Republic Donation Voucher, file # 1319, GLO ↩︎

-

Samuel L. Chambliss, Republic Pension Files, Republic Pension Records, Texas Comptroller’s Office claims records. ARIS-TSLAC, 384 ↩︎

-

Samuel L. Chambliss, John S. Chambliss, United States Sixth Census (1840), Jefferson County, Mississippi, M707, Roll 214 ↩︎

-

Menn, The Large Slaveholders of Louisiana-1860, 175 ↩︎

-

Carrington, Women in Early Texas, 73 ↩︎

-

Muir, Texas in 1837, 171-2; Frederick Law Olmsted, A Journey Through Texas or a Saddle-Trip on the Southwestern Frontier, 43 ↩︎

-

Joseph William Schmitz, Thus They Lived: Social Life in the Republic of Texas, (San Antonio: The Naylor Company, 1936), 38 ↩︎

-

Dobie, The Flavor of Texas, 174 ↩︎

-

Carrington, Women in Early Texas, 258; Smith, A Good Home for a Poor Man, 54 ↩︎

-

Salley, The History of Orangeburg, South Carolina, 79; Jones and Warren, South Carolina Immigrants, 1760 to 1770, iv ↩︎

-

Mullins, The Ancestors of George and Hazel Mullins, 5 ↩︎

-

Carrington, Women in Early Texas, 163 ↩︎

-

Freund, Gustav Dresel's Hoiston Journal, 56 ↩︎

-

Mr. and Mrs. Nate Winfield, All Our Yesterdays: A Brief History of Chappell Hill, (Waco: Texian Press, 1969), 2 ↩︎

-

Muir, Texas in 1837, 35, 50; Bobby D. Weaver, Castro’s Colony, Empresario Development in Texas, 1842-1865, (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1985) 4-5 ↩︎

-

Muir, Texas in 1837, 14-5 ↩︎

-

McDonald, Jose Antonio Navarro, 141 ↩︎

-

McDonald, Jose Antonio Navarro, 93, 107, 142; Carrington, Women in Early Texas, 197 ↩︎

-

Pryor, “Tom Rife, An 1890’s Custodian of the Alamo,” 44 ↩︎

-

Rena Maverick Green, Editor, Samuel Maverick, Texan: 1803-1870, A Collection of Letters, Journals and Memoirs, (San Antonio: Privately Published, 1952), 90; McDonald, Jose Antonio Navarro, 162 ↩︎

-

Dobie, The Flavor of Texas, 66 ↩︎

-

Noah Smithwick, The Evolution of a State or Recollections of Old Texas Days, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1900), 81-3 ↩︎

-

Dobie, The Flavor of Texas, 57, 64 ↩︎

-

Jimmy L. Bryan, Jr., More Zeal Than Discretion: The Westward Adventures of Walter P. Lane, (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2008) 9, 11-2; Green, Samuel Maverick, Texan, 103; S.C. Gwyenne, Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanche’s, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History, Scribner, New York, 2011, 139 ↩︎

-

Homer S. Thrall, History of Methodism in Texas, (1872, reprint, n.p.: Walsworth Publishing, 1976), 9 ↩︎

-

Winfield, All Our Yesterdays, A Brief History of Chappell Hill, 2 ↩︎

-

Louisiana Marriages, 1718-1925, Book E, East Carroll Parish, Nathaniel Chambliss, Caroline Hale, www.ancestry.com, accessed December 22, 2013 ↩︎

-

Nathaniel Chambliss 2nd Class Headright Certificate 104, Washington County Commissioners May 22, 1839, GLO ↩︎

-

Samuel Lytle and Nathaniel Chambliss, Land Grants, Washington County Clerk Returns, 1838, file 000013, GLO; Ellis A Davis and Edwin H. Grobe, compilers, New Encyclopedia of Texas Vol. III, (Dallas: Texas Development Bureau, 1929), 2205; Anonymous, A Twentieth Century History of Southwest Texas, Vol. 1, Chicago, New York and Los Angeles: The Lewis Publishing Co., 1907), 285 ↩︎

-

Affidavits of Witness’, Mexican War Pension Application ↩︎

-

Muir, Texas in 1837, 165; Louis White, First Settlers of Washington County, Texas, (St. Louis, G. White, 1986), 2 ↩︎

-

John Lott, Land Grant, Montgomery County Clerk Returns, 1st Class Certificate 78, GLO ↩︎

-

County Deed Records, Book D, 102, Washington County Clerks Office, Brenham, TX; Washington County, Texas Deed Abstracts Vol. 1, Republic of Texas and the State of Coahuila and Texas (Mexico), 99 ↩︎

-

Winfield, All Our Yesterdays: A Brief History of Chappell Hill, 2 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Express, March 30, 1919 ↩︎

-

The Daughters of the Republic of Teas, Real Daughters, (Dallas: Daughters of the Republic of Texas, Inc., 2007), 18; Application for Membership of Mary R. Fly, Daughters of the Republic of Texas ↩︎

-

Paul C. Boethel, Colonel Amasa Turner, The Gentleman From Lavaca and Other Captains at San Jacinto, (Austin: Von Boeckman-Jones, 1963), 64; Paul C. Boethel, History of Lavaca County, (Austin: Von Boeckman-Jones, 1959), 85 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Express, March 30, 1919 ↩︎

-

Gifford White, ed., First Settlers of Washington County, Texas, (St. Louis: G. White, 1986), 28 ↩︎

-

Nathaniel Chambliss 2nd Class Headright Certificate 104, Washington County Commissioners May 22, 1839, GLO ↩︎

-

Texas National Register (Washington, Texas), June 05, 1845; Gifford White, 1840 Citizens of Texas: Vol. 2, Tax Rolls, (St. Louis: Ingmire Publications, 1984), 260 ↩︎

-

Hugh Best, Debrett’s Texas Peerage, (New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1983), 360 ↩︎

-

White, 1840 Citizens of Texas Vol. 2, Tax Rolls, 260 ↩︎

-

Gerald S. Pierce, Texas Under Arms: The Camps, Posts, Forts & Military Towns of the Republic of Texas 1836-1846, (Austin: The Encino Press, 1969), 143 ↩︎

-

Green, Samuel Maverick, Texan, 150; McDonald, Jose Antonio Navarro, 161 ↩︎

-

McDonald, Jose Antonio Navarro, 180; James Kinnen Greer, Colonel Jack Hays: Texas Frontier Leader and California Builder, (New York: E.P. Dutton and Co., 1952), 63 ↩︎

-

William Corner, comp. and ed., San Antonio De Bexar: A Guide and History, (1890, repr. San Antonio, TX: Graphics Arts, 1977), 136; A. J. Sowell, Early Settlers and Indian Fighters of Southwest Texas, (Abilene: State House Press, McMurry University, 1986), 343 ↩︎

-

Samuel Bogart, Public debt claims, Texas Comptroller's Office claims records. ARIS-TSLAC; Telegraph and Texas Register (Houston) May 9, 1838; Joseph Milton Nance, After San Jacinto, The Texas-Mexican Frontier, 1836-1841, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1963), 77; Mrs. Harry Joseph Morris, Founders and Patriots of the Republic of Texas, (Austin: Daughters of the Republic of Texas, 1963),Vol 1: 63 ↩︎

-

County Deed Records, Book F, 130, Washington County Clerks Office, Brenham, Texas ↩︎

-

Green, Samuel Maverick, Texan, 159; Francis S. Latham, Travels in the Republic of Texas, 1842, (Austin: Encino Press, 1971), 5, 25 ↩︎

-

Pat Gordon, indexer, Washington County Texas Court of Commissioners of Roads and Revenue, 1836-1846, (Ft. Worth: GTT Books, 2001), 48 ↩︎

-

Homer S. Thrall, History of Methodism in Texas, 92 ↩︎

-

Deed Records of Washington County Clerks Office, Book F, 85,115, ↩︎

-

L. G. Park, ed., Twenty-Seven Years on the Texas Frontier by Captain William Banta and J W Caldwell, Jr., (Council Hill, Oklahoma: n. p., 1933), 49; Boethel, Colonel Amasa Turner, 65 ↩︎

-

Thrall, History of Methodism in Texas, 73 ↩︎

-

Robert A. Divine, T. H. Breen, George M. Fredrickson and R. Hal Williams, America Past and Present, (New York: 4th Edition, Harpers-Collins College Publishers, 1995), Vol. 1: 317 ↩︎

-

White, First Settlers of Washington County, Texas 45 ↩︎

-

White, First Settlers of Washington County, Texas, 54; Nathaniel Chambliss, Unconditional Headright Certificate # 543, Bounty Land Commissioners for Washington County, file 893, GLO ↩︎

-

Nathaniel Chambliss, United States Seventh Census (1850), M432, Lavaca County, Texas, M432; Bill of sale, County Deed Records, County Clerks Office, Lavaca County, Book C, 33-4, Hallettsville, TX ↩︎

-

Republic Claims, Republic of Texas, Comptrollers Records, Public Debt, Reel 143, ARIS-TSLAC, Austin, 314 ↩︎

-

Register of Brands, County Clerks Office, Lavaca County, Texas, 39, 74, 152, Hallettsville, Texas; Deed Records of Lavaca County, County Clerks Office, Book B, 325, Hallettsville, Texas; Paul C. Boethel, The Free State of Lavaca, (Austin: Weddle Publications, 1977), 163 ↩︎

-

Surveyors notes for the Bounty Land Grant of Nathaniel Chambliss in Erath County, Abstract 155, File 000983, GLO ↩︎

-

T. R. Fehrenbach, Seven Keys to Texas, (El Paso: Texas Western Press, The University of Texas at El Paso, 1983), 17 ↩︎

-

Probate Court of Lavaca County, County Clerks Office, No. 320, 634-48, Hallettsville, Texas ↩︎

-

Boethel, The Free State of Lavaca, 159; Indenture, County Deed Records, County Clerks Office, Lavaca County, Book C, 30-1, Hallettsville, TX ↩︎

-

Frank S. Gray, Pioneering in Southwest Texas: True Stories of Early Day Experiences in Edwards and Adjoining Counties, (Austin: The Steck Company, 1949), 56-8; Carrington, Women in Early Texas, 297 ↩︎

-

Fehrenbach Seven Keys to Texas, 80 ↩︎

-

Boethel, Colonel Amasa Turner, 64; Boethel, The Free State of Lavaca, 159 ↩︎

-

Galveston Weekly News, June 15, 1858 ↩︎

-

Carrington, Women in Early Texas, 193; Carol C. Green, Chimborazo: The Confederacy’s Largest Hospital, (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2004), 59 ↩︎

-

Nathaniel Chambliss, United States Eighth Census (1860), Hallettsville, Lavaca County, Texas, Roll M653 ↩︎

-

Brenda Lincke Fisseler, comp., We Are Gathered Here: Lavaca County Marriage Records 1846-1869, (Hallettsville, TX: Old Homestead Publishing Co., 2000) ↩︎

-

Deed Records of Lavaca County, County Clerks Office, Book F, 77 ↩︎

-

Deed Records of Lavaca County, County Clerks Office, Book G, 724-9 ↩︎