History of the Alamo, 1718–1881

“From 1885 to 1894 Rife was custodian of the Alamo”

— “Custodian of the Alamo”, San Antonio Light, February 23, 1887

The Alamo was established in 1718.

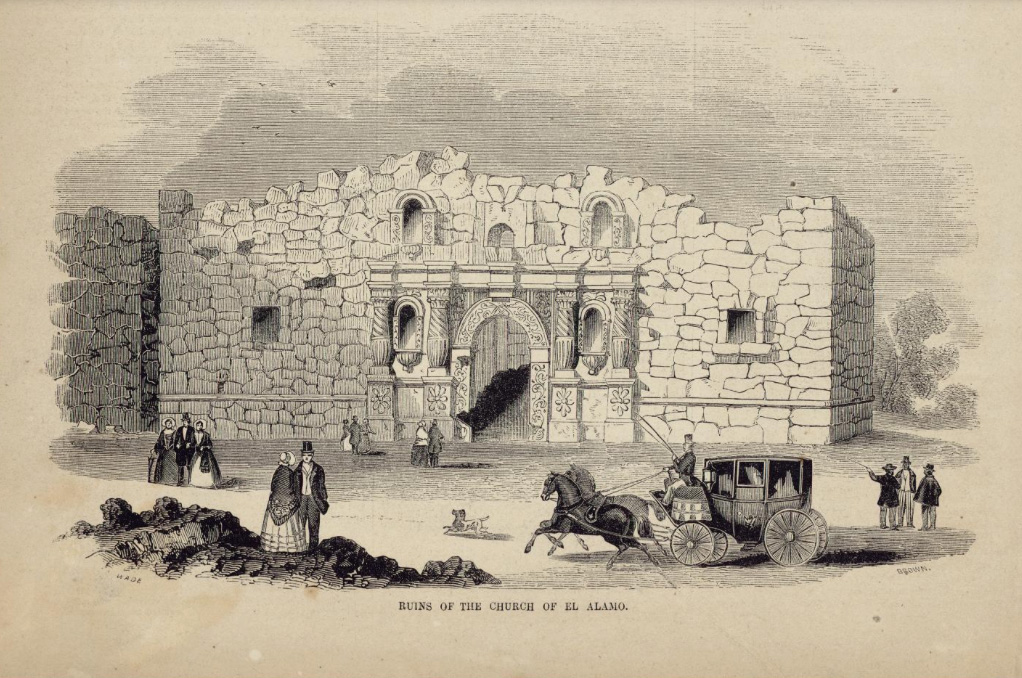

Fray Antonio de Olivares, a Franciscan missionary, established Mission San Antonio de Valero (now called the Alamo) for the Payaya Indians. The mission was a school where the Native Americans were taught Spanish culture and the Catholic religion.1 The mission enclosure was built in the form of a rectangle. Living quarters for the Indians were on the opposite side of a plaza from the church and priests’ residence.2 Construction of the church was begun in 1744 and was finished in 1757. The church’s two towers, its arched roof and the dome collapsed in 1762 because of faulty construction.3 Disease epidemics, as well as a decline in the number of Indians living at the mission, caused a labor shortage. Due to this shortage, the church was never rebuilt and remained a ruin.4 Epidemics killed so many Indian converts at the mission that by 1778 there were not enough laborers to work the mission’s fields.5

From 1690 until September 10, 1772, the Spanish Crown paid the expenses of the San Antonio missions.6 Mission San Antonio de Valero was secularized7 in August 1793. The mission and its few remaining residents were transferred from the care of missionary fathers to that of the local parish.8 Because of a shortage of diocesan priests, the Franciscan missionaries agreed to stay on as parish priests. The mission was administered as part of the parish of Béxar.9

Ten years later, a cavalry company from El Alamo de las Parras (now Viesca, Coahuila) occupied the former priests’ residence10 until 1813, and the priests’ residence became known as the Long Barracks.11 By 1807 the Alamo was no longer referred to as a mission but as a Spanish fort. In August 1825, the chaplain of the company of Alamo de Parras transferred the company’s sacramental records to the church at Béxar.12 Between 1807 and 1812, the upper floor of the Long Barracks was used as a hospital.13

By 1807, of the five missions along the San Antonio River, only Mission San José still had Indians residing on the mission grounds. In 1823, that mission closed, and the land and irrigation rights of Mission San José were distributed to private individuals.14 In 1821 the village government of Béxar (now called San Antonio) asked that the remaining unassigned land of the Mission Valero (the Alamo) be assigned to it.15 In September 1825, title to all the remaining mission buildings passed to the Bishop of Monterrey, whose diocese included the village of Béxar. The Church subsequently repurchased some property that had fallen into private hands.16

The Spanish government closed its presidios (forts) in east Texas in 1793 and moved the settlers to Béxar. In February of that year, people from the Presidio of Adaes, which was located west of Natchitoches in what is now Louisiana, were assigned land at the Valero mission. After the Alamo mission was closed in August, the village of La Villita was built south of the Alamo enclosure on land that had once belonged to the San Antonio de Valero mission.17 Because it was on higher ground, several families moved west of the river after a flood in 1819. After annexation in 1845, La Villita became a German neighborhood.18

The Alamo was besieged in 1836.

In 1830 the military facilities at the Alamo were expanded onto expropriated private property.19 General Martin Perfecto de Cos rebuilt the fortifications at the Alamo20 just before surrendering to the Texans in December 1835.21 There were also fortifications on Military Plaza that the Mexicans staffed with a second company of troops.22 After the Texans captured the town, the fortifications on Military Plaza were abandoned and all the guns moved to the Alamo fort. They blocked the doors of the Long Barracks facing the mission plaza with rammed earth and installed loopholes.23 A loophole is an opening in a wall just large enough for a standing man to use as a firing port. They erected a cedar post stockade, ditch, and earthworks at gaps in the exterior walls.24

When General Santa Anna’s army arrived on the morning of February 23, 1836, the fort and the predominantly American force inside was besieged.25 General Santa Anna made it clear that if his army had to storm the fort, he would execute its defenders. At times, Mexican troops withdrew from the eastern side of the fort in the hope that the defenders would take the opportunity to flee.26 Most of the Tejano men of Béxar, who had entered the fort with the Texas Federalists and their American allies, left during the siege.27 The remaining men, mostly Americans who had only recently arrived in Texas, were prepared to die to defend the Alamo.28

In the early morning of Sunday, March 6, the fort was stormed and captured by the Mexican Centrist army.29 There were less than two hundred men and about a dozen women and children in the fort when it was attacked.30 Most of the women and children sheltered in rooms on the north side of the church; they were away from the primary fight at the Long Barracks and were not injured.31 When Colonel Travis refused to surrender the fort, General Santa Anna placed a red flag on the tower of San Fernando Church, signifying “No Quarter”32 and everyone understood that all armed men found inside the Alamo would be killed.33 During the assault, the Mexican army’s band played an ancient melody called “de querella,” signaling that no prisoners were to be taken. Most of the approximately 182 defenders were killed when the fort fell on that infamous day.34

After the battle, Mexican General Andrade first began to fortify the Alamo and then had his troops dismantle the fortifications before moving to join the main Mexican army at Goliad. Before surrendering to the Americans in December 1835, General Cos had torn down the remaining arches of the church and built a ramp from debris that extended from the main door of the church to its rear. There he installed a wooden platform upon which he mounted an 18-pound cannon.35 General Andrade’s troops set the wooden platform on fire before they left for Goliad. The high walls surrounding the mission plaza were leveled, the moat filled up, and the cedar pickets were torn up and burnt.36 The Long Barracks and the ruins of the church were left intact.37 The outer walls on the west and south sides of the plaza were stone or adobe soldiers’ quarters that faced the plaza. The rear of these houses formed the outer wall of the mission enclosure. These walls were also left intact.38

A visitor to the Alamo in 1842 described the Alamo as having 12 to 15 apartments, separated by stonewalls several feet thick. He understood that the defenders of the Alamo were pursued into the convent or Long Barracks and killed there.39 He made no mention of the church that stood to one side and behind the Alamo fort. The old fort remained a ruin and a place where children played until about 1850.40 In 1845 the 2nd Illinois Regiment of the US Army built a carpentry shop inside the old walls before the regiment departed for Mexico.41 For many years the only other buildings in the neighborhood were flat-roofed adobe houses just south of the Alamo in the old Barrio of Valero.42

The US Army occupied the Alamo from 1846 to 1878.

On January 13 and 18, 1841, the Congress of the Republic of Texas passed an act granting the mission churches and surrounding improvements to the Catholic Church.43 The images of Saints Dominic and Francis were removed from the niches on the front of the Alamo church shortly afterward.44 The crucifix and other sacred objects had been removed to San Fernando Church long before.45

Towards the end of 1846, the United States Army took possession of the Alamo property and began paying rent to Mr. Bryan Callaghan as an agent of the Bishop in April 1847.46 The Army attempted to get possession of the fort by pre-emption, but Samuel Maverick, a resident and land speculator, convinced them that the Alamo was a mission, not a fort and therefore not public property.47 He then had the site surveyed and built a house on the northwest corner of the property on land he purchased from a resident.48

By 1847 only the Long Barracks, the ruined church, and portions of the west and south walls (specifically the Low Barracks) remained. The US Army, under Major Babbitt, removed much of the debris from the church, built a peaked, shingled roof over the shell of the building, and raised the parapet of the church to hide the peaked roof.49 San Antonio architect John Fries, who designed the parapet extension, added two upper windows on the west face of the building.50 A peaked roof was added to the Long Barracks, and it was renovated as offices.51 The old fort was used as the Quartermaster’s Depot52for the 8th Infantry for the next thirty years.53

The Army built a barracks at the corner of Houston and St. Mary’s Street in San Antonio and rented the Vance Building (the Brick Building) as the Army’s Headquarters.54 In 1860, the US Quartermaster, 8th Infantry, had his office in the Brick Block that the Army rented from Vance Brothers.55 A subordinate branch of the Quartermaster Department under Captain A. W. Reynolds, Assistant Quartermaster, occupied the Alamo.

The building fronting the common (i.e., the Long Barracks) was a two-story building used for offices, storerooms, packing rooms, saddler’s shop, harness room, and a wagon shed.56 In a corral behind the Long Barracks were mule sheds. On the east side of the street behind the Long Barracks was the corral for wagons, a carpenter’s shop, a smith’s shop, and a hay yard.57 The first floor of the old church building was used as a granary. The architect added a second floor to the church, and R. M. Potter, a military storekeeper, occupied it. Mr. Potter had charge of the camp, garrison, and clothing stores.58 The Quartermaster employed over 129 persons, 820 mules, one horse, and 198 wagons, many of them in and around the Alamo.59

A flood destroyed parts of San Antonio along the San Antonio River60 in March 1865; the Bishop asked the US Army to vacate the Alamo church so the German Catholic congregation of San Antonio could use it. Major General Merritt replied that the Quarter Master Department was using the building for receiving grains, and losing its use would be a “great inconvenience and serious loss.”61 St. Joseph’s Church was subsequently built nearby for German-speaking Catholics.62

The Diocese no longer needed the Alamo church after the new church was built.63 According to local legend, the statue of Saint Anthony of Padua was then removed from the lower right-hand niche on the Alamo’s façade. This removal signified that the angels guarding the church had withdrawn their protection and that the building was no longer considered holy ground.64

On May 19, 1868, a hailstorm caused much damage in San Antonio and destroyed the shingle roofs of the Alamo buildings.65 US Army headquarters were moved to Austin the next year but then returned to San Antonio in 1875. During this time, the church was still being used by the Army to store grain. The City donated 93 acres for Post San Antonio (now called Fort Sam Houston), and in May, work began on the new post.66 The first building completed at Fort Sam Houston was the Quadrangle occupied by the Quartermaster in January 1878. Shortly afterward, the Army left the Alamo property.67

The Alamo was sold for commercial use in 1879.

In 1879 Honoré Grenet purchased the Long Barracks from the Catholic Church for $19,000 for use as a retail store.68 He refaced the exterior with wood made to resemble a military fortress.69 Mr. Grenet built wooden galleries around the two-story building (which had been only slightly damaged in 1836) to replicate the missing stone arcades, added towers with wooden cannons, and painted the words, “The Alamo Building” on the west and south sides.70

Honoré Grenet died unexpectedly in 1882, and two years later, the estate was sold at auction to the firm of Hugo-Schmeltzer, a wholesale distributor of groceries and liquors, for $28,000.71 The firm moved its offices to Houston Street after a few years and, after that, used the Long Barracks as a warehouse.72 It appears that Hugh & Schmeltzer continued to lease the old church as well.73

The State purchased the Alamo church.

In April 1881, the 18th Texas Legislature passed an act authorizing the Governor to purchase the Alamo church building from the Bishop of San Antonio.74 The City Council of San Antonio adopted a resolution proposing to take charge of the Alamo church “to preserve it as a monument and prevent its desecration” on the provision that the State buy the building.75

-

Adina De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo and Other Missions in and around San Antonio, (San Antonio: Standard Printing Co., December, 1917), 7; Robert S. Weddle and Robert H. Thonhoff, Drama & Conflict: the Texas Saga of 1776, (Austin: Madrona Press, Inc., 1976), 136 ↩︎

-

Adina De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo, 11; Weddle, Drama & Conflict, 136 ↩︎

-

De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo, 18 ↩︎

-

De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo, 10; Charles Ramsdell, San Antonio: A Historical and Pictorial Guide, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1959), 18; Weddle, Drama & Conflict, 135 ↩︎

-

Ramsdell, San Antonio, 18; Weddle, Drama & Conflict, 136 ↩︎

-

James L. Rock and W. I. Smith, Southern & Western Texas Guide for 1878, (St. Louis, MO: A. H. Granger Publishers, 1878), 28 ↩︎

-

Weddle, Drama & Conflict, 142 ↩︎

-

De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo, 13 ↩︎

-

Wright, San Antonio de Bexar: An Epitome of Early Texas History, (Austin: Morgan Printing, 1916), 69; Adina De Zavala, The Alamo: Where the Last Man Died, (San Antonio: The Naylor Company, 1956), 8 ↩︎

-

Gale Hamilton Shiffrin, Echoes from Women of the Alamo, (San Antonio: AW Press, 1999), 215 ↩︎

-

Ramsdell, San Antonio, 19; Shiffrin, Echoes from Women of the Alamo, 214 ↩︎

-

Ramsdell, San Antonio, 19, 31; De Zavala, The Alamo, 10 ↩︎

-

Ramsdell, San Antonio, 20 ↩︎

-

David McDonald, Jose Antonio Navarro, In search of the American Dream in Nineteenth-Century Texas, (Denton, TX: Texas State Historical Association, 2010); Weddle, Drama & Conflict, 142 ↩︎

-

McDonald, Jose Antonio Navarro, 56 ↩︎

-

Mrs. S. J. Wright, San Antonio de Bexar: An Epitome of Early Texas History, 153 ↩︎

-

McDonald, Jose Antonio Navarro, 34 ↩︎

-

Ramsdell, San Antonio, 99 ↩︎

-

McDonald, Jose Antonio Navarro, 92 ↩︎

-

Shiffrin, Echoes from Women of the Alamo, 215 ↩︎

-

De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo, 18; Leonora Bennett, Historical Sketch and Guide to the Alamo, repr, (San Antonio, TX: James T. Roney, 1904), 39 ↩︎

-

McDonald, Jose Antonio Navarro, 114 ↩︎

-

De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo, 18; Rena Maverick Green, Editor, Samuel Maverick, Texan: 1803-1870, A Collection of Letters, Journals and Memoirs, (San Antonio: Privately Published, 1952), 54; De Zavala, The Alamo, 15 ↩︎

-

De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo, 21 ↩︎

-

Bennett, Historical Sketch and Guide to the Alamo, 51 ↩︎

-

McDonald, Jose Antonio Navarro, 230; Bennett, Historical Sketch and Guide to the Alamo, 53 ↩︎

-

Green, Samuel Maverick, Texan, 55 ↩︎

-

McDonald, Jose Antonio Navarro, 226 ↩︎

-

De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo, 33; Bennett, Historical Sketch and Guide to the Alamo, 60 ↩︎

-

De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo, 30 ↩︎

-

De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo, 36 ↩︎

-

De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo, 184 ↩︎

-

Bennett, Historical Sketch and Guide to the Alamo, 53 ↩︎

-

Ramsdell, San Antonio, 83 ↩︎

-

Ramsdell, San Antonio, 19, 70; Green, Samuel Maverick, Texan, 32 ↩︎

-

De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo, 38 ↩︎

-

De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo, 45, 55 ↩︎

-

Ramsdell, San Antonio, 149 ↩︎

-

Gerald S. Pierce, ed., Travels in the Republic of Texas, 1842 by Francis. S. Latham, Austin, TX: Encino Press, 1979, 35; Ramsdell, San Antonio, 20 ↩︎

-

De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo, 20, 63; Donald E. Evertt, San Antonio: The Flavor of its Past, 1845-1898, (San Antonio: Trinity University Press, 1975), 18; Wright, San Antonio de Bexar: An Epitome of Early Texas History, 97 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Light, August 18, 1888; San Antonio Daily Express, August 19, 1888 ↩︎

-

McDonald, Jose Antonio Navarro, 34 ↩︎

-

De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo, 43 ↩︎

-

Ramsdell, San Antonio, 76 ↩︎

-

Ramsdell, San Antonio, 167 ↩︎

-

De Zavala,History and Legends of the Alamo, 44; Susan Prendergast Schoelwer, “The Artist’s Alamo: A Reappraisal of Pictorial Evidence, 1836-1850”, The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 91, No. 4, (April, 1988), 445, 448 ↩︎

-

Green, Samuel Maverick, Texan, 323 ↩︎

-

Ramsdell, San Antonio, 76; Schoelwer, “The Artist’s Alamo: A Reappraisal of Pictorial Evidence, 1836-1850”, 451 ↩︎

-

De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo, 10; (468, Shiffrin, Echoes from Women of the Alamo, 216 ↩︎

-

Ramsdell, San Antonio, 77 ↩︎

-

Shiffrin, Echoes from Women of the Alamo, 216 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Light, March 29, 1887, 87 ↩︎

-

George Wythe Baylor, Into the Far, Wild Country: True Tales of the Old Southwest, (El Paso: Texas Western Press, The University of Texas at El Paso, 1996), 3 ↩︎

-

Wright, San Antonio de Bexar, 88; Evertt, San Antonio, 123; Frank S. Faulkner, Jr., Historic Photos of San Antonio, (Nashville and Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing Company, 2007), 2 ↩︎

-

Jerry Thompson, ed., Texas and New Mexico on the Eve of the Civil War: The Mansfield and Johnston Inspections, 1859-1861, (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2001), 173 ↩︎

-

Schoelwer, “The Artist’s Alamo: A Reappraisal of Pictorial Evidence, 1836-1850”, 445 ↩︎

-

Thompson, Texas and New Mexico on the Eve of the Civil War, 175 ↩︎

-

Thompson, Texas and New Mexico on the Eve of the Civil War, 176 ↩︎

-

Thompson, Texas and New Mexico on the Eve of the Civil War, 175 ↩︎

-

William Corner, comp. and ed., San Antonio De Bexar: A Guide and History, (1890, repr, (San Antonio: Graphics Arts, 1977), 137; Wright, San Antonio de Bexar, 113 ↩︎

-

De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo, 44 ↩︎

-

William Corner, comp. and ed., San Antonio De Bexar: A Guide and History, ,161 ↩︎

-

Faulkner, Jr., Historic Photos of San Antonio, 45; De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo, 44 ↩︎

-

De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo, 57 ↩︎

-

Vinton Lee James, Frontier and Pioneer Recollections, (San Antonio: Artes Graficas, 1938), 46; Corner, compiler and editor, San Antonio De Bexar: A Guide and History, 144 ↩︎

-

Ramsdell, San Antonio, 214; Wright, San Antonio de Bexar, 90 ↩︎

-

Shiffrin, Echoes from Women of the Alamo, 216 ↩︎

-

Corner, comp. and ed., San Antonio De Bexar: A Guide and History, 163 ↩︎

-

Shiffrin, Echoes from Women of the Alamo, 116; De Zavala, The Alamo, 47 ↩︎

-

Corner, comp. and ed., San Antonio De Bexar: A Guide and History, 158; De Zavala, History and Legends of the Alamo, 57 ↩︎

-

Corner, comp. and ed., San Antonio De Bexar: A Guide and History, 143; Shiffrin, Echoes from Women of the Alamo, 219 ↩︎

-

Faulkner, Jr., Historic Photos of San Antonio, 16; Alexander Edwin Sweet, Alex Sweet’s Texas: The Lighter Side of Lone Star History, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986), 11 ↩︎

-

Ramsdell, San Antonio, 77 ↩︎

-

Francis R. Pryor, “Tom Rife-an Early Alamo Custodian”, STIRPES 42, No. 2, (June 2002), 28; De Zavala, The Alamo, 47 ↩︎

-

Pryor, “Tom Rife-an Early Alamo Custodian,” 28; Bennett, Historical Sketch and Guide to the Alamo, 85 ↩︎