George Giddings’ second mail contract, July 1857–February 1862

“It was always a mystery to me that he could employ men who would take their lives in their hands to carry out that contract”

— Captain G. Walker.1

Mail service between San Antonio and San Diego was set to begin in 1857.

On June 30, 1857, Giddings’ contract to carry the mail between San Antonio and Santa Fé ended. On the next day, a new contract to carry the mail on through to San Diego, California, was scheduled to begin. Nine contractors were competing for the new route, designated as route number 8076. One of them was James E. Birch, from Swansea, Massachusetts. He had been in the stage business for eleven years and had owned and managed the California Stage Company.

James Birch was ready for a new venture and, when he learned that bids were being taken for a new transcontinental stage line, was prepared to act quickly. His only serious competitor was the Butterfield Company, a creation of the Adams, American, National, and Wells Fargo express companies. Birch bid $600,000 a year for semiweekly service on the route favored by the Postmaster General. Except for one potential obstacle, Birch was confident of winning the contract. The problem was that John Butterfield, head of the Butterfield firm, was a personal friend of President Buchanan.

In the end, the Postmaster General hedged by awarding contracts on two transcontinental routes as allowed by the 1856 appropriations bill. Birch received the contract for route number 8076 for $149,800 to provide semimonthly service to San Diego with connections to the Lower Road from San Antonio.2 Butterfield received a contract for $600,000 for semiweekly service from St. Louis, Missouri, to San Francisco. Both routes to begin service on July 1, 1857. The Butterfield route started at St. Louis and then, to avoid winter snow, turned southwest toward Texas, where it crossed Colbert’s Ferry on the Red River. The route then ran 282 miles to Fort Chadbourne on the Colorado River. From Fort Chadbourne, it ran in a westerly direction to Franklin (now El Paso, Texas), a distance of 458 miles.3

The mail service provided by Birch and Butterfield was the first regularly scheduled mail connecting California and the eastern States. It was not, however, the first overland mail service to California. The US military had carried mail to California since 1847. US Army express couriers carried mostly military dispatches, but they did carry some civilian mail as well. Birch’s contract provided for a true trans-continental postal service. The mail from the eastern States would be collected at New Orleans and then sent to Indianola, Texas, by steamer. Then it was hauled 130 miles by wagon to San Antonio and prepared for the trip to San Diego, California.4

James Birch selected Isaiah Churchill Woods to manage the enterprise. Isaiah Woods, in turn, appointed his brother-in-law Robert E. Doyle as the San Francisco agent and James E. Mason as the San Antonio agent. Woods set out from New York for San Antonio, where he intended to ride the mail stage to San Diego and meet James Birch. Unfortunately, the steamship to Indianola arrived late, and he missed the connecting stage to San Antonio.

The first mail to California left San Antonio on July 9, 1857.

Mason presented his credentials to the San Antonio Postmaster on July 9 and collected the mail bound for California. With a crew of guards and station keepers and a herd of mules to stock relay stations along the way, the men left amidst a cheering crowd gathered in the plaza.5

According to the San Francisco Bulletin, “On the 31st of August, at noon, James E. Mason and party arrived at San Diego in charge of the U.S. overland mail. The parties left San Antonio on the 9th and 24th of July; consequently, those who left on the 24th had made the trip in thirty-eight days.” It continued, “Mr. Mason left San Antonio on the morning of the 9th of July, in company with four men. The time afforded for preparation was exceedingly short so that no relays of mules could be sent ahead. Even the animals ridden by the party had to be picked up as they could, at a few hours notice. This caused a material delay, which was still further augmented by the sickness of the conductor. At El Paso, however, they took an ambulance and had proceeded as far as Cienega de Sauz, where they were overtaken by the party that left San Antonio with the mail of the 24th, in charge of Capt. James [Henry] Skillman. He had come in an ambulance the entire distance from San Antonio, without encountering any difficulty on the road. The two parties then proceeded together as far as the Pima Villages, when Mr. Mason took both mails, and with one companion, pushed on with pack-mules, making the trip to San Diego, in the unequaled time of nine days, across the worst part of the entire route, including the great Colorado Desert."6

The article continued, “The immigration across the Southern route is reported by the mail riders to be quite large, upwards of one hundred wagons having been passed, with considerable quantities of stock. As the mail riders, however, traveled mostly in the night, they had not much opportunity to elicit information from the immigrants.”7

The second mail to California left San Antonio on July 24, 1857.

Isaiah Woods hired William “Bigfoot” Wallace to manage a supply train that stocked the relay stations and Henry Skillman to conduct the mail coach. Skillman left with the second westbound mail on July 24, 1857, with a Celerity wagon for the guards and the mail sack and also a canvas-covered spring wagon with water, provisions, and mule feed.8 The amount of actual mail was small.9 Another supply train had been sent out earlier on July 1, consisting of three wagons, 38 mules, 17 men, and two tons of supplies for the relay stations.

The next day, Woods followed on the El Paso bound stagecoach. Giddings intended to travel from San Antonio to El Paso on the mail coach scheduled to leave on August 9.10 Woods met Wallace on the road beyond Castroville and heard first-hand the first of the many reports of bad news. When Woods met Wallace, he and his men were mounted on mules borrowed from the Army.

Wallace told Woods that Comanche raiders sprang out of the brush fifteen miles above Camp Hudson and surprised Wallace and his party. The mules pulling the wagon panicked and ran into the brush, breaking the wagon pole. Wallace and a companion named William Clifford (of New Orleans) jumped off and ran for the mule herd. Wallace reached a mule, jumped on, and ran for his life. Clifford, not so lucky, was lanced in the back and fell. “The mail party fought the Comanche for about two hours, but the Indians were too numerous for them; they took all the mules, coach, saddles, and in fact, all that the mail party had."11 After the fight, Wallace led a patrol of US cavalry back to bury Clifford’s body and salvage the wrecked wagon. Fifty-four mules were stolen; only the six that the men were riding were saved.12 Wallace and his men turned back toward San Antonio and met Woods’ coach on the way. The 2d Cavalry, under the command of Captain Whiting, pursued the Indians and recaptured the stolen mules, but they were no longer suitable for mail service.13

Meanwhile, Doyle made a late start from San Diego because of a shortage of mules there. His small party finally got underway on August 9th with pack mules carrying the mail. What followed was a month of confusion, breakdowns, missed rendezvous, and late deliveries as the freight men got organized. Order was eventually restored. Over the next year, the average time to make the 1,476-mile trip was 27 days.

George Giddings and the Birch line merged.

On August 4, 1857, the Army discontinued its semi-weekly express service due to “the recent increases of mail facilities between this city (San Antonio) and the posts along the road to New Mexico.”14 To ensure the safety of the mail, Major General Twiggs, commander of the Department of Texas, issued Special Order number 91. It instructed the post commanders at Forts Clark, Lancaster, and Davis to furnish from four to eight men on the application of Isaiah Woods “to proceed from post to post as far as Fort Bliss with the semi-monthly mails in charge of himself or his agents, the transportation to be supplied by Mr. Woods. They [the US Army] will also give protection to any horses or mules he may leave at their posts, and permit an employee of his to remain with them.”15 After this policy was in place, infantry soldiers accompanied the mailmen. The soldiers traveled in a wagon provided by the mail company.

On September 2, 1857, Woods proposed to Giddings that they merge their operations. After thinking the matter over for a few days, Giddings accepted. Giddings’ men would take the mail to Santa Fé, and he would receive a salary. It made sense to cooperate with Woods since the two contractors were running wagons along the same roads, and Giddings owned the relay stations between San Antonio and El Paso.

Transcontinental passenger service commenced in October 1857.

The fifth mail party arrived in San Diego on October 5, just 26 days and 12 hours after leaving San Antonio, setting a new speed record.16 In less than three months, they cut time to make the trip from 53 days to 26 ½ days. Based on this success, Woods placed an ad in the San Diego Herald announcing passenger service to the east from San Francisco to New Orleans. Re-enforcing that announcement, on October 18, the coach from San Antonio brought four paying passengers, each paying a fare of $200. Happily, the coach was on schedule!

On October 23, 1857, Woods left San Diego on the eastbound stage for El Paso. Upon arriving at Fort Yuma, he received news that threatened to undo all of his efforts. James Birch had drowned in the Atlantic Ocean on September 13 when the steamer “Central America” sank in a storm.17 Woods’ suppliers, who knew that the mail line operated on Birch’s credit, demanded payment when they received news of Birch’s death. Without the backing of Birch, Woods knew that he would be hard put to get the credit he needed to continue operating.18 In another ominous turn of events, the Butterfield Company, with its deep pockets, signed a contract to begin mail service on September 15, 1857. Woods had no choice but to continue on his way to San Antonio as scheduled.19

Woods and Giddings left San Elizario on Christmas day 1857 for San Antonio, knowing that the only way to straighten out the tangled finances was to talk to the man who had assumed control of the firm from Mr. Birch’s widow. The two men spent New Year’s Day on the road and arrived at Fort Lancaster only to learn that the coach conducted by Silas St. John, who had left El Paso a few days before them, arrived at Fort Lancaster to find the relief mules there had been stolen. Flooded rivers and a standoff with forty Comanche Indians delayed both parties as they continued to Fort Clark with worn-out mules. The trip was stressful for all involved. The passengers riding in the first coach arrived in San Antonio on December 31. They cheered when the tower of San Fernando church came into sight, grateful that their once-in-a-lifetime adventure was over.20 Meanwhile, the coach that Woods and Giddings were riding in became mired in a snowstorm and lagged behind. Two mounted men were sent ahead with the mail, and the coach proceeded slowly, arriving at San Antonio on January 17, 1858.

That winter, Indians mounted a series of attacks on the mailmen and their property. Mescalero Apaches emptied the corrals at the relay stations at La Limpia and Dead Man’s Hole. The contents of the stations were destroyed, and 26 mules stolen.21 The mail party was attacked. The conductor and his guards fought the Indians for some time. They managed to escape by putting the mail on the fore-wheels of the coach, leaving behind two coaches and sets of harnesses, which the Indians destroyed.22 The relay station at Van Horn’s Well and its contents were also destroyed. The losses included between 25 and 75 tons of hay valued at $50 per ton23that the hay contractor, George Lyle, had brought in just the day before.24 Twenty-six mules were also taken.25

Giddings went to Washington, D.C. to make his case before Postmaster General Brown.

The postmaster met with Mrs. Julia Birch’s attorney, who admitted that Giddings had a claim to the mail contract. The firm’s new owner, who had received ownership from Mrs. Birch, then ceded the San Antonio to San Diego mail contract to Giddings. Giddings received a new contract for Route number 8076 for twice a month (semi-monthly) service paying $149,800 per year beginning on January 1, 1858. The contract ran for three and a half years.26

At this time, Giddings was working with the California Steam Navigation Company “to make the trip between San Francisco and San Diego in two days, connecting with the overland mail. This, with a proper connection at Indianola, it is expected will give a certain and reliable communication overland in thirty days—to be reduced, after a while to perhaps twenty-five days.”27

However, not all the news was good. Congress had not yet passed an appropriations bill for the Post Office, so Giddings received certificates of indebtedness instead of bank drafts. He could only hope that the San Antonio banks would honor the notes without heavily discounting them.28 There was also a clause in that contract that would later hurt Giddings, i.e., the Postmaster General had the authority to curtail or discontinue any part of the route at his discretion.29

The Butterfield Company prepared to begin service in October 1858.

The Butterfield Company was preparing to begin carrying mail in the fall. The Butterfield Company employed 800 men to build the post road, dig wells and build 141 relay stations along the 2,800-mile route. The company bought 250 coaches and 1500 horses and mules. The Butterfield route started in St. Louis and Memphis, converged at Little Rock, then joined Giddings’ route at El Paso. Since the Butterfield route did not cross the populated parts of Texas, it was of little commercial value to Texas except for the connection at El Paso.30 Giddings first heard from Isaiah Woods of a rumor that portions of the Giddings’ route west of El Paso would be canceled since his route and that of the Butterfield Company followed the same road.

In what was to be the first of several curtailments, the Postmaster General terminated Giddings’ contract between El Paso and Santa Fé in October 1857. He gave it to Thomas F. Bowler for a contract price of $16,250 per year. It appears that Bowler could not perform this service satisfactorily, and Simon Hart, an El Paso merchant, bought the contract for $11,800 in June of 1859.31 In short order, the Postmaster General curtailed another part of Giddings’ route. The section of the mail route between El Paso and Fort Yuma was granted exclusively to the Butterfield Company, and Giddings was left with two disconnected mail routes, i.e., San Antonio to El Paso and Fort Yuma to San Diego. He was allowed an increase from $149,800 to $196,448 because service was also increased from twice a month to weekly deliveries. There was no allowance for the expense of dismantling his stations in the discontinued section.32 The Postmaster General cited duplication of service between El Paso to Fort Yuma as the reason for the curtailment.33

Giddings offers passenger service to San Diego.

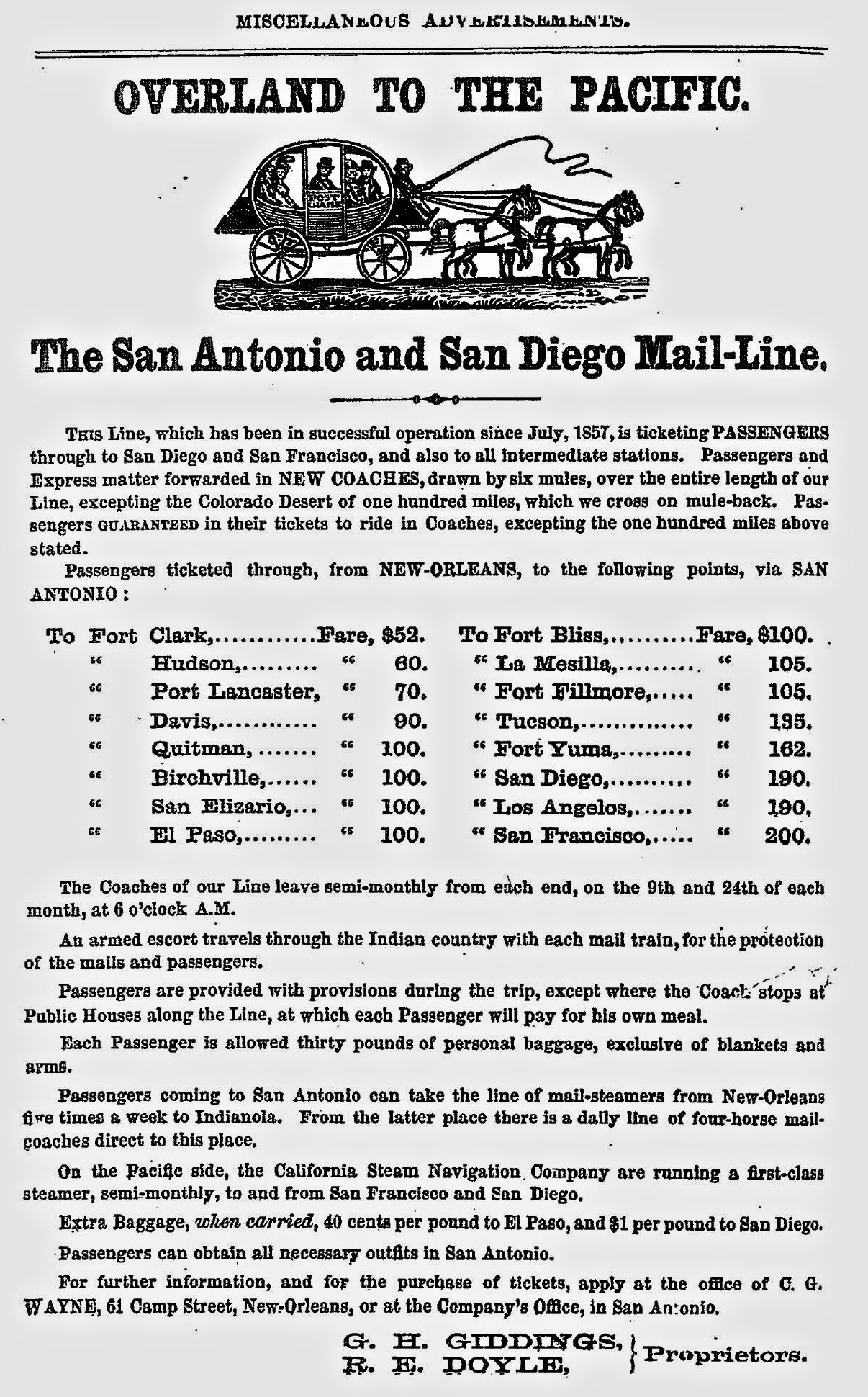

In a newspaper advertisement dated July 10, 1858, proprietors of the stage line, George H. Giddings and Robert E. Doyle, offered passenger service to San Diego and all stops between in new coaches with six-mule teams. They guaranteed that the passengers would ride the entire way in these new coaches except for 100 miles across a sand desert west of Tucson.34

The new coaches were undoubtedly Concord Coaches built by the Abbot-Downing Company of Concord, NH. They supplied stagecoaches to all the critical lines in the West. Each coach accommodated nine passengers inside and one or more outside, in addition to the driver and guard. The front seat faced backward while the middle seat was removable and had little or no back support. The back seat faced forward and was considered the most desirable and the first to be reserved. The body of the coach was made of white oak braced with iron. The body, which was built without springs, swung on stout three-inch-thick leather bands that permitted it to swing back and forth and side to side. The coach could also carry as much as 600 pounds of mail.35

During this period, the volume of mail snowballed. In October 1858, the Giddings line carried 2,509 letters. In October 1859, it carried 64,000 letters; by March 1860, Giddings was carrying 112,645 letters per month. In 1859, the company employed 59 drivers and 50 coaches pulled by over 400 mules36 in addition to support personnel who manned the relay stations and guarded the mail trains. Freight and passenger traffic increased proportionally. On October 21, 1858, the coach arriving in San Antonio under Captain Holliday brought the mail and four passengers. The passengers reported, “…the trail was crowded with cattle drovers bound for the west.”37

In the spring and summer of 1858, Giddings began rebuilding ruined relay stations and started the construction of new ones. The mail company’s relay stations were spaced about 25 miles apart and were kept stocked with items, such as corn, that were most often required by travelers. It was estimated that at least two thousand westward-bound emigrants used the Lower Military Road each year. The Sacramento Union newspaper praised both Butterfield and Giddings when it wrote, “The weary emigrant will no longer be left to protect himself against the incursion of the Indians night after night, and with nothing to subsist his teams on…He will camp under the roof of the mail station, or in the vicinity, feed his teams with grain and hay, rest safely…”38 Stage stations were constructed in the form of a quadrangle with a single entrance. The two rooms inside the station had no exterior doors. The stations were designed to be impregnable against Indian attacks unless provisions of the besieged defenders ran out before help arrived.39

In addition to providing protection and supplies to travelers, the mail contractor’s employees at the relay station were sometimes the only representative of the Government (other than the Army) that many people saw regularly. Sometimes the stations became “embryonic courthouses, with their residents serving as magistrates and jurors.”40 Lt. Zenas Bliss wrote in his memoirs of a man who shot and killed another in a saloon about midnight. The Brackettville station agent, Tom Rogers, who was also a Justice of the Peace, was awakened and, ”organized his court, tried the murderer, acquitted him, and the man was back dealing Monte…in an hour or two from the time he shot the victim.”41

The US military protected the mail service.

On June 4, 1858, Major General Twiggs issued a second order, Special Order number 50, to the commanding officers of posts along the road used by mail contractors. The order stated that the commanders “will permit the mail Company to erect sheds and corrals sufficiently near to receive the protection of their posts.”42

In the fall of 1858, the Army established a new fort a few miles north of the Birchville mail station on the Rio Grande. Birchville was the name given to a mail station located where the San Antonio-El Paso Road left Quitman Canyon at the Rio Grande. Two to three men manned the station.43 For some reason, Fort Quitman was built six miles above the Birchville station44, although the original intention was to locate the post where the road joined the river.45 The mail station moved to be near Fort Quitman, renamed Quitman Station. Fort Quitman offered protection to the stage station and established a US Army presence on a lonely stretch of the border with Mexico.

Travel by stagecoach in 1858 was dangerous and unpleasant.

While the Texas newspapers generally supported Giddings’ efforts to provide mail and passenger service,4647 California papers found reasons to complain about the service. For the benefit of greenhorn travelers, one paper published a list of supplies that a traveler on the stage should take along. The list included, “One Sharp’s rifle and a hundred cartridges; a Colt’s Navy revolver and two pounds of balls; a knife and sheath; a pair of thick boots and woolen pants; a half-dozen pair of thick woolen socks; six undershirts; three woolen over-shirts; a wide-awake hat; a cheap sack coat; a soldier’s overcoat; one pair of blankets in summer and two in winter; a piece of India rubber cloth for blankets; a pair of gauntlets; a small bag of needle and pins, a sponge, hair brush, comb, soap, etc. in an oil-silk bag; two pairs of thick drawers, and three or four towels.”47 While the first thirty pounds of luggage was included in the fare, excess baggage cost one dollar per pound, so these extra items, which might save the passenger’s life, increased the cost of travel.

A young man named Phocion R. Way left Ohio for the silver mines of Arizona in May 1858. He arrived in San Antonio and booked passage on the stagecoach. This journey was his first sight of the frontier. He kept a diary of his journey and left an illuminating account of travel on the frontier. He characterized his traveling companions as “citizens with the bark on.” He learned the hard way why most passengers preferred to sleep on the ground rather than with the fleas in the station beds. He survived a gunfight, a hailstorm, threat of Indian attacks, the steep road down to Fort Lancaster, heat, dust, the chill of a “norther,” a prairie fire, and wretched roads. He learned to eat, relax, and sleep with a rifle within reach. He did not blame the stage employees for his travel experiences and called them “fine fellows.”48

Sometimes, as happened on May 20, 1859, there were too many passengers for the regular mail coach, and an additional coach was added to accommodate all. George F. Pierce, a minister, rode such a coach and recorded his impressions. He described the ritual of mealtimes away from a station or other shelter: “On stopping, all the employees of the stage line spread themselves in quest of fuel. A few dry sticks were soon gathered – the fire kindled, the kettle put on, and water heated; an old bag is brought from its resting place in the stage boot. Its open mouth laid upon the ground, the other end is seized and suddenly lifted, and outcomes tin-cups and plates, iron-spoons, knives and forks, helter-skelter; another bag rolls slowly out, containing the bread; presently another cloth is unrolled, and a piece of beef appears. Now a box is brought forth, the lid is raised, and we behold coffee, tea, sugar, salt, pepper, and pickles – a goodly supply.” Then “the ground coffee is put in, water poured on, and all well shaken – the coals are ready, and the pot boils. By this time, the frying-pan is hot, the lard melted, the meat sliced, and soon our senses are regaled by the hissing urn and the simmering flesh…“ He followed by observing, “The table-cloth of many colors, all inclined to dark, as innocent of water as the loom that made it, is spread upon the ground. Plates, tin-cups, knives, and forks are arranged in order, and Ramon announces: ‘Supper ready, gentlemen.’ All hands gather about ‘the cloth,’ oblivious of dirt, careless of dainties, and the necessaries of life disappear very rapidly. The fragments are left for the prairie wolf and the birds of the air; the cloth is shaken, and on its dingy surface a few more spots appear, of the same sort, however, only a little more lively from being fresh; the unwashed instruments are boxed and bagged, and we are ready to travel.”49

Tom Rife encounters runaway slaves and more Indian attacks.

In December 1858, a slave catcher named Solomon C. Childers arrived on the stage to San Antonio, bringing with him “a valuable negro” that Childers had recaptured in Chihuahua.50 The reward for the slave’s return was the usual $200, which was a large sum, considering that slaves were rarely armed. Childers praised the stage employees calling the conductors “a capital set, especially our friends, Frank and Thomas.” This reference is one of the first mentions of Rife after he returned to the mail service since he left for California in 1853.

In the same month, on December 8, Thomas Rife brought the stage into the Eagle Springs station on a cold December night only to find the station burning. Two dead and scalped bodies of white men lay nearby. (One was the stationmaster named Chips). Rife heard an account of the attack from a Mexican man who was employed to tend the stable and harness the relief mules. In the terminology of the day, this man was known as a hostler. Having fled into the brush during the attack, the hostler witnessed the looting of the station and theft of all twelve mules.51 This attack was the second time the Eagle Springs station was destroyed.52

In July 1860, the mail party with Rife as a conductor, Free Thomas as a driver, and Jack Hodge and C. W. “Clown” Garner as guards, captured two escaped slaves near Devil’s River. The slaves, a man, and a woman were the survivors of a group of three slaves who had escaped from their owners on the Colorado River and came close to starving as they made their way to Mexico. One man became desperate enough to kill the other and cook and eat him. The mail party partook of the meat, thinking it was bear meat. When they realized what they were eating, Jack Hodge recounts, “You should have seen our faces, some long, some broad, and of changeable colors. I think I was green. Well, that bear meat didn’t stay with us long. My innards felt like the government of Mexico, rather unsettled, that is the way we all felt excepting Clown, who was wearing one of his comical grins peculiar to Clown only”. Hodge went on to say, “We carried them to San Antonio and got the reward all right.”53 The reward for escaped slaves found west of the Colorado River was $200, which amounted to five months pay for a stage guard and a year’s pay for most laborers.

The Butterfield Company began service in October 1858.

The first delivery of mail by Giddings’ competitor, The Butterfield Company, arrived in San Francisco on November 10, 1858. The Butterfield Company was well-financed and could pay higher wages than could Giddings and other stage operators. Some of Giddings men, including Bradford Daily, Silas St. John, and Henry Skillman, left Giddings’ employ to work for the Butterfield line.

Skillman was given charge of the section of the road between Horsehead Crossing and El Paso. After building a new station on the west bank of the Pecos, Skillman drove a Butterfield stage. In September 1857, he became famous for driving the first westbound Butterfield stage from Horsehead Crossing on the Pecos to El Paso without relief, a distance of some 250 miles.54 Bradford Daily, who replaced Tom Rife as Conductor on Skillman’s line in 1853, signed on as a driver. He was murdered while helping to build a Butterfield mail station on the Pecos.55 Another of Giddings’ conductors, Silas St. John, also signed on with the Butterfield line as a stationmaster.

On January 28, 1859, the New Orleans Postmaster was ordered to make up a weekly mail pouch for San Francisco to be forwarded over Giddings’ route. Previously the San Francisco mail had been forwarded to St. Louis. No provision was made to fund this extra service. For the next three months, until April 1859, Giddings had the mail picked up at the Indianola post office and brought to San Antonio without receiving compensation from the Post Office Department.56

Postmaster General Brown died unexpectedly in February 1859 and was succeeded by Joseph Holt. On June 1, 1859, Holt ordered Giddings to reduce his weekly service to 24 trips per year at a contract price of $120,000. Giddings offered to continue the weekly trips and to rely on Congress for payment, but orders were sent to the local postmasters to “refuse delivery of the mails to the agents” of Giddings.57

Giddings’ California mail service discontinued in April 1860.

A hint of fresh trouble appeared in January 1859, when Congressmen from northern States began to voice opposition to Giddings’ mail service because of its location in a slave state;58 Isaiah Woods, who was still employed by the coach line, went to Washington to monitor the situation.59

On February 1, 1860, the US House of Representatives finally elected a Speaker after months of rancorous debate. There still was no postal appropriation bill. It was an election year, and Congress was engrossed in struggling with an ever-growing list of issues that threatened to lead the country into civil war. The Alabama legislature had already called for a secession convention if the nation elected a Republican for president in November 1860.60

Giddings was in Washington, D.C., when he learned that Postmaster General Holt had ordered that the Pacific end of Giddings route (San Diego to Fort Yuma) be discontinued in April 1860, and the Giddings contract reduced to $91,305 per year. This change meant that a large number of mules and a large amount of stage property in California would have to be either sold or taken seven hundred miles back to Texas.61 The men would have to be laid off or brought back to Texas unless they could hire on with the new carrier. The Postmaster General continued to cut Giddings’ contract. On May 1st, he announced that the Butterfield Company would move their route south to cross the Pecos River at Horsehead Crossing and then continue to Comanche Springs.62 After this change, Giddings’ route would end at Fort Stockton. The contract amount would accordingly be reduced to $53,726 per year.63 However, Giddings continued to run coaches to El Paso at a loss, and his men continued to operate the relay stations between Comanche Springs and El Paso.64

The Butterfield stagecoach drivers took the mail forwarded from San Antonio only when they had room, and by October 1860, a considerable amount of mail had accumulated at both El Paso and Comanche Springs.65 The Post Office Department did not modify the mail contract to compensate the Butterfield line for the additional mail. Despite problems with the Post Office Department, Giddings’ mail stages continued to provide high-grade service. On March 7, 1860, the mail reached San Antonio from El Paso in just four days and seventeen hours.

In May of 1860, the news from Washington, D.C., was not auspicious. The Republican Party was running Abraham Lincoln for President. The Democrats, having split into two factions, lost any chance of winning the Presidential election. Congress adjourned without passing a postal appropriation bill. Giddings was in Washington, along with representatives of many other mail carriers, all of whom were anxious to be paid. The Postmaster General issued promissory notes to the mail carriers. Giddings used his certificates as collateral for loans. He also heard that the Butterfield Company was lobbying to have their route moved farther north in anticipation of a war. Giddings was hopeful that the change would benefit his company.66

On July 5, 1860, gold was discovered on the Membres River in what is now Arizona. The news sparked a rush of men from the Mesilla Valley and the town of Mesilla.67 The Mesilla newspaper closed for lack of printers, and employees of the mail company deserted the stage stands to become gold miners.68 The El Paso and San Diego mail arrived at San Antonio on October 6, 1860, with the news that two men had been killed in an attack on Dempsey’s train near the Pecos Station. The Indians also drove off or slaughtered a herd of 250 goats found near the station. Thirty soldiers were dispatched from Fort Lancaster by its commanding officer, Captain Carpenter, to give chase.69 Tom Rife mentioned this incident later in a deposition taken in 1892.70

Abraham Lincoln’s election led to secession.

In the national elections of November 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected President of the United States. His election energized the Southern secessionists. By the time South Carolina seceded, in December 1860, Indians had struck La Limpia, Van Horn’s Well, and Beaver Lake stations. The stations at Leon Holes and El Muerto were attacked shortly afterward. By then, more important events taking place elsewhere overshadowed news of Indian depredations. Many Union men, including Giddings, still held out hope that a conflict between the States would be averted. These hopes dimmed when Mississippi seceded on January 9, 1861, followed by Florida, Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana, all in seventeen days. On January 28, 1861, the secession convention met in Austin and voted in favor of submitting the question to the electorate. A majority of the State’s voters, some 46,000, voted in favor of secession.71

The new Postmaster General offered Giddings a new four-year mail contract. It was for a route to run from San Antonio to Los Angeles, beginning on April 1, 1861.72 At that time, most Americans thought that the conflict between the Federal government and the Southern States would be settled peacefully and that the mail service would be allowed to continue as before until the Union and the Confederacy could agree to a treaty.73

Indian raids on the mail service continued as before. In January 1861, a supply train camped at Pecos Station was attacked. The station was damaged, and 109 mules were stolen.74 Captain Albert Bracket, the army commander at Camp Hudson, sent troops after the Indians. He “had the loaded wagons hauled into his post and kept them guarded until the claimant (Giddings) sent up mules from San Antonio to take the wagons to El Paso.”75

Also, in January 1861, Quitman Station (located about 250 yards from Fort Quitman) was robbed of 12 horses and 32 mules. About 60 Apaches attacked the station that was defended by 16 or 17 men.76 One man, described as a Yankee named Billy Fink, was killed. The Howard Wells station was also destroyed in January 1861 and was never rebuilt. Rife witnessed the theft of 18 good mules from the station at Barilla Springs in March 1861.77 On February 25, 1861, Dan Murphy wrote from Fort Davis describing an Indian attack on mail coaches and freighters along the Lower San Antonio-El Paso Road. He told of the loss of about 100 mules laden with copper. The next overland mail coach, conducted by T. Davis and driven by J. Steward, was charged by 25 Indians.78 The protection provided by the US Army, insufficient as it was, was lost when, in mid-February, General Twiggs surrendered all Federal Forces in Texas to State and Confederates authorities. In early spring 1861, the US Army began to withdraw from the Texas frontier.79

The Butterfield Company shifted its route north to avoid Texas in 1861.

The Butterfield Company re-routed its stages north of Texas. The last eastbound coach from El Paso arrived in St. Louis on March 21, 1861.80 In April 1861, Noah Smithwick and a party of California emigrants reported that the stage stations on the Butterfield line between Fort Chadbourne and the Pecos River were dismantled and deserted and the ferry at the Horsehead Crossing of the Pecos was destroyed.81 Only four men occupied Fort Quitman when Smithwick’s party passed near.82 These men were either the vanguard of Baylor’s force from San Antonio or, more likely, James Magoffin’s caretakers from El Paso who were charged with protecting Federal property abandoned by the US Army.

On April 1, 1861, George Giddings and his brother James were on board the westbound stage when it left San Antonio. George was on his way to meet with Butterfield representatives at Fort Stockton to buy their remaining stock and equipment.83 James Giddings was headed to California to organize men and material for the resumption of the mail contract to Los Angeles. George completed the transaction, buying all the equipment from Fort Stockton to California, belonging to the Butterfield Company. He also purchased the site of the army post and the mail station at Comanche Springs from John D. Holloway.84 Giddings then set out for El Paso on a trip during which he saw his closest brush ever with death.

With Parker Burnham in the driver’s box and the coach three miles west of the station at Barilla Springs, a band of Mescalero Apaches sprang from the brush and unleashed a hail of arrows. The driver Burnham was wounded in the hip and the neck. The guard, Jim Spears, took the reins and urged the mules toward the station’s gate at a dead run. Three of the mules had arrows in their flanks. The passengers shot four Indian warriors out of their saddles before reaching the safety of the station. While the battle continued from inside the station, the three mules died of their wounds. Finally, Chief Nicolas’s braves gave up and left. Burnham survived the operation that removed the arrows and, once healed, joined a Confederate cavalry unit.85 Burnham was among the lucky men who survived their wounds. Between 1857 and 1861, the Giddings mail line running between San Antonio and San Diego suffered the death of 111 Americans and 57 Mexicans. Indians raiders caused most of the fatalities.

Apaches attacked the mail trains in response to the Bascom Affair.

With the army gone, Indian raids escalated. When Giddings reached El Paso, he learned that his brother, James, had died on April 2886 in an attack in New Mexico.87 The massacre of the mail party was the response to what is known as the “Bascom Affair.”88 In February 1861, US Army Lt. George N. Bascom hung the brother and nephews of the Chiricahua Apache leader, Cochise, at Fort Buchanan in what became the State of Arizona. This action led to the 25-year war with the Western Apache and was the chief cause of the destruction of Giddings’ mail stations in Arizona in June 1861.

The Eagle Springs station was destroyed for the third time in June, and 12 mules were stolen.89 Giddings was returning to San Antonio to learn what the Confederate Government would do about mail service to the West when he saw the graves of those who were killed. The station was not rebuilt.90

On May 17, 1861, a mail party of two six-mule coaches led by Free Thomas left Mesilla bound for California. Following the mail-train were 100 men and the remaining Butterfield stock that Giddings had not purchased.91 George Giddings and Henry Skillman followed with 25 men and livestock to replenish the mule herds at Giddings’ western stations. Apache Indians led by Cochise and Mangas Coloradas attacked the mail party when it got ahead of the larger group. The twelve men in the mail party were chased to Cook’s Spring station and killed along with the station’s crew.92

In addition to the Cook’s Spring station, seven other stations between Mesilla and Tucson were destroyed.93 More than thirty men were killed, at least six coaches were destroyed, and over 100 horses and mules were stolen. George Giddings testified that the Indians destroyed “the route between Mesilla and Tucson, over 300 miles, stealing all my stock on that part of the route, over 180 head, destroyed all my stations except one, and much other valuable property and killed some 40 of my men.”94 Scores of Sharps Rifles and Colts Revolvers fell into the hands of the Indians as a result of the attacks. These weapons would make the Apaches even more formidable in the future.

Giddings and Henry Skillman, with a 25-man party, stopped at each burned outstation and buried the dead. Giddings returned to El Paso numbed and even more in debt. Henry Skillman took over as superintendent of the line west of Mesilla, and a newspaper notice optimistically announced the resumption of service to California.95

The stage route east of El Paso was somewhat less affected by Indian attacks. An article in The “Daily Ledger and Texan” newspaper of San Antonio reported on June 4, 1861, that Giddings had 24 station houses built of stone or adobe between San Antonio and El Paso, each staffed by three to five armed men, and that he had stocked the road with 300 mules and horses. The mail was running regularly twice a week to El Paso in 6½ days. The newspaper reported that there were more than 100 men employed on the line.96

The first Confederate troops arrived in West Texas in July 1861.

Rife’s mail party met a group of Confederate troops on July 9, 1861, between Dead Man’s Hole and Van Horn’s Well. The mail party, which was heading west to El Paso, met the group of Confederate volunteers from San Antonio as they were burying one of their men who had been struck by lightning. On July 10, 1861, Rife was seen leading the mail party near El Muerto (Dead Man’s Hole) west of Van Horn’s Well. The mail coach was headed to El Paso.97 Three days later, Rife and his party were seen 30 miles west of San Elizário headed east toward San Antonio.98 On this trip, Rife and the mail coach passed Waller’s and Baylor’s Confederate regiments on their march from San Antonio to El Paso.

The month before, in June 1861, George Giddings rode on the San Antonio stage, driven by David Koney. When the coach arrived at the destroyed station at Eagle Springs, the passengers and crew paused to bury the two dead men and then proceeded east, passing the deserted army post at Fort Davis and the mail station at La Limpia. Once back home, Giddings, like many Northern-born men, faced the question of where his loyalties lay. Would he throw his support to the Union or the Confederacy? Giddings ultimately decided to remain in Texas and support the new government.

In June, Giddings received a letter informing him that Confederate Government would not recognize his Federal contract beyond June 30, 1861.99 Instead, he would need to bid for a mail route from the Confederate Post Office Department when the San Antonio Postmaster advertised for bids on new contracts.100 If he did not win that contract, Giddings would have to sell out or lose his investment in the stagecoach line.

The new CSA Postmaster was Stephen H. Reagan, a former US Congressman from Texas. Reagan retained those post office employees who wished to work for the Confederacy and secretly hired essential people from the U.S. Postal Service. He ordered all contractors already operating to continue until new contracts could be awarded. Giddings was, as always, hopeful that he would eventually be paid for his services. According to the Mesilla Times of December 12, 1861, Henry Skillman had “taken the contract to carry the mail from Mesilla to El Paso, Texas, on horseback, once a week, and has already commenced the service."101 The Confederate government paid him $250 for “three trips to Fort Thorn and …one trip to Alamosa,”102

On February 17, 1862, the US Postmaster General discontinued service on the route between El Paso and San Antonio. Either in defiance of the Postmaster-General or ignorance of his order, Giddings’ employees tried to maintain service to California. A week before Confederate troops captured Fort Fillmore, the final U.S. mail from San Diego arrived in Mesilla. Federal troops intercepted the last southbound mail from Santa Fé near Mesilla on its way to El Paso.103 By then, the upper Rio Grande valley was a war zone.

The Confederate invasion of New Mexico was a failure.

In May 1862, Rebel forces under Confederate General Henry Sibley retreated from Glorietta Pass, north of Santa Fé in New Mexico Territory, and began a long retreat back to San Antonio. Mail service from El Paso was still running, although many stations were destroyed, and the water wells polluted by Indian raiders.104 The mail continued to run until August 16, 1862, when the last stage from El Paso arrived in San Antonio. Four days later, the First California Volunteer Cavalry under Lt. Col. E.E. Eyre of the US Army took possession of Fort Bliss and occupied the settlement that later became El Paso, Texas.105

Nevertheless, on August 28, 1862, Giddings signed contract number 8075 with the Confederate Post Office for twice-weekly service between Mesilla and San Antonio and from Mesilla to San Diego every two weeks for $60,000. Giddings’ anticipated that the route west of Mesilla would likely not be serviceable because Federal troops and Indian raiders prevented wagons from Texas going beyond El Paso.106 The contract ran until June 30, 1865.107

Fort Clark became the western terminus of the mail service.

In practice, the mail was forced to stop operations west of Fort Clark by August 1862, due to the destruction of the relay stations.108 In September, a band of paroled Confederate troops under Lieutenant Edward L. Robb walked from El Paso to San Antonio and attested to the destruction of the mail stations.

Giddings summed up almost ten years of his life when he said, “I made repeated efforts to carry the mail, but I was compelled to abandon the route…”109 William “Big Foot” Wallace was asked, “Did you ever recover, or did Col. Giddings ever recover, any of the property that was taken, and that was under your charge?” He answered, “I never did, and he never did.”110

Giddings activities as a mail contractor were confined entirely to Texas after 1862. In December 1862, he and a new partner, B.R. Sappington, signed a contract for a branch route from Uvalde to Eagle Pass. This was a profitable route because postage and passage from Mexico were paid in silver.111 There is no evidence that Giddings attempted to serve as a mail contractor after the war. Even if he wished to do so as an ex-Confederate officer, he would have been barred from bidding on federal contracts.112

-

Deposition of John G. Walker, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Clayton Williams, Never Again, Texas 1848-1861 Vol. 3, (San Antonio: The Naylor Co. 1969), 154 ↩︎

-

Clarence R. Wharton, Texas Under Many Flags, (Chicago: The American Historical Society, Inc., 1930), 45 ↩︎

-

Stuart N. Lake, “Birch’s Overland Mail in San Diego County”, The Journal of San Diego History, San Diego Historical Society Quarterly 3, (April 1957) ↩︎

-

Robert H. Thornhoff, San Antonio Stage Lines 1847-1881, (El Paso Western Press, 1971), 15; Anonymous, The Texas Almanac for 1859, (Galveston, TX: The Galveston News, 1859), pp. 139-40 ↩︎

-

San Francisco Bulletin, September 9, 12, 1857 ↩︎

-

San Francisco Bulletin, September 9, 12, 1857 ↩︎

-

Anonymous, The Texas Almanac for 1859, 139; Lake, “Birch’s Overland Mail in San Diego County”; The Southern Intelligencer, (Austin), October 21, 1857 ↩︎

-

Thornhoff, San Antonio Stage Lines, 1847-1881, 15 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 94 ↩︎

-

The Weekly Independent (Belton, Tex.), August 15, 1857 ↩︎

-

Deposition of William A. Wallace, Giddings vs. The United States; Petition from Giddings, Giddings vs. The United States; Deposition of George H. Giddings, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 96; Civilian and Gazette (Galveston), September 1, 1857 ↩︎

-

Records of the War Department, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Special order 91 ordering Post commanders to supply escorts to mail parties, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 106 ↩︎

-

Statement to the Senate and the House of Representatives, Giddings vs. The United States; Anonymous, The Texas Almanac for 1859, 139 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 112; Anonymous, The Texas Almanac for 1859, 139 ↩︎

-

Anonymous, The Texas Almanac for 1859, 139 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 115; San Antonio Daily Herald, December 31, 1857 ↩︎

-

Petition from Giddings, Giddings vs. The United States. ↩︎

-

Deposition of William M. Ford, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Petition from Giddings, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Deposition of Tom Rife, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Deposition of Tom Rife, Giddings vs. The United States; Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 117-9 ↩︎

-

Statement to the Senate and the House of Representatives, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Civilian and Gazette (Columbus, TX), March 30, 1858 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 121 ↩︎

-

Statement to the Senate and the House of Representatives, Giddings vs. The United States. ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 133 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 143 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 143 ↩︎

-

Statement to the Senate and the House of Representatives, Giddings vs. The United States. ↩︎

-

Thornhoff, San Antonio Stage Lines, 1847-1881, 16; The Galveston News, “The Texas Almanac, for 1860, with Statistics, Historical and Biographical Sketches, Etc., Relating to Texas, (1860): University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, http://www.texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth123766/ (accessed June 30, 2012) ↩︎

-

San Antonio Sunday Light, July 16, 1939 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Sunday Light, July 16, 1939 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 142 ↩︎

-

Sacramento Union, March 5, 1859 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Sunday Light, July 16, 1939 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 138 ↩︎

-

Thomas T. Smith, et al, Ed, The Reminiscences of Major General Zenas R. Bliss 1854-1876, (Austin: Texas State Historical Assoc., 2007) 178 ↩︎

-

Records of the War Department, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Jerry Thompson, ed., Texas and New Mexico on the Eve of the Civil War: The Mansfield and Johnston Inspections, 1859-1861, (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2001), 107 ↩︎

-

Thompson, Texas and New Mexico on the Eve of the Civil War, 69. ↩︎

-

The Belton Independent (Belton, TX), October 16, 1858 ↩︎

-

The San Antonio Ledger, Saturday, May 22, 1858 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 122 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 124-7 ↩︎

-

George G. Smith, The Life and Times of George Foster Pierce, D.D., LL.D, (Sparta, GA: Hancock Publishing Co., 1888), 382-3 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 142 ↩︎

-

Deposition of Tom Rife, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Deposition of George H. Giddings, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Jerry Thompson, From Desert to Bayou: The Civil War Journal and Sketches of Morgan Wolfe Merrick, (El Paso: University of Texas at El Paso, 1991), 38-40; Olmstead, A Journey Through Texas or a Saddle Trip on the Southwestern Frontier, 326-7 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 141 ↩︎

-

Houston Telegraph, October 20, 1858 ↩︎

-

Statement to the Senate and the House of Representatives, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Statement to the Senate and the House of Representatives, Giddings vs. The United States; Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 146 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 146 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 145 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 154-5 ↩︎

-

Statement to the Senate and the House of Representatives, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Patrick Dearen, Crossing Rio Pecos, (Fort Worth: Texas Christian Press, 1996), 11 ↩︎

-

Kathryn Smith Mcmillen, “A Descriptive Bibliography on the San Antonio-San Diego Mail Line,” The Southwest Historical Quarterly 59, (October 1955): 206-14; Statement to the Senate and the House of Representatives, Giddings vs. The United States. ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 157 ↩︎

-

The Daily Ledger and Texan (San Antonio), October 29, 1860 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 158. ↩︎

-

The Daily Ledger and Texan (San Antonio), July 26, 1860 ↩︎

-

The Daily Ledger and Texan (San Antonio), July 5, 1860 ↩︎

-

The Daily Ledger and Texan (San Antonio), October 6,1860 ↩︎

-

Deposition of Tom Rife, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Mark Swanson, Atlas of the Civil War Month by Month: Major Battles and Troop Movements, (Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 2004), 4 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 161; The Daily Ledger and Texan (San Antonio), June 4, 1861 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 163. ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 164; Petition from Giddings, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Deposition of William A. Wallace, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Deposition of Joseph Hetler, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Deposition of Tom Rife, Giddings vs. The United States; Petition from Giddings, Giddings vs. The United States. ↩︎

-

The Daily Ledger and Texan, (San Antonio), February 25, 1861 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 164. ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 165. ↩︎

-

Noah Smithwick, The Evolution of a State or Recollections of Old Texas Days by Noah Smithwick, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 19830, 254 ↩︎

-

Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier: Fort Stockton and the Trans-Pecos, 1861-1895, 12 ↩︎

-

Wayne R. Austerman, “The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, CSA,” West Texas Historical Association Year Book 58, (1980), 79 ↩︎

-

Thompson, Texas and New Mexico on the Eve of the Civil War: The Mansfield and Johnston Inspections, 1859-1861, 225; Williams, Texas’ Last Frontier: Fort Stockton and the Trans-Pecos, 1861-1895, 64 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 166-7. ↩︎

-

Deposition of Joseph Hetler, Giddings vs. The United States; Deposition of George H. Giddings, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

San Antonio Sunday Light, July 16, 1939 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 168. ↩︎

-

Petition from Giddings, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Deposition of George H. Giddings, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Wayne R. Austerman, “The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, CSA,” 80 ↩︎

-

Times-Picayune (New Orleans), June 7, 1861; Deposition of Joseph Hetler, Giddings vs. The United States; Petition from Giddings, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Wayne R. Austerman, “The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, CSA,” 80 ↩︎

-

Deposition of George H. Giddings, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 170. ↩︎

-

The Daily Ledger and Texan (San Antonio), June 4, 1861 ↩︎

-

Thompson, From Desert to Bayou: The Civil War Journal and Sketches of Morgan Wolfe Merrick, 19 ↩︎

-

Thompson, From Desert to Bayou: The Civil War Journal and Sketches of Morgan Wolfe Merrick, 23 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 176. ↩︎

-

Wayne R. Austerman, “The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, CSA,” 86 ↩︎

-

The Charleston Mercury (SC), January 16, 1862. ↩︎

-

Henry Skillman, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, 1861-1865, M346, RG 109, NARA, Roll 941 ↩︎

-

Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 180. ↩︎

-

Wayne R. Austerman, “The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, CSA,” 94 ↩︎

-

Nancy Lee Hammons, Thesis, A History of El Paso County, Texas, to 1900, (El Paso: The University of Texas at El Paso, 1983), 49 ↩︎

-

Wayne R. Austerman, “The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, CSA,” 87-8 ↩︎

-

Wayne R. Austerman, “The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, CSA,” 88; Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, 181 ↩︎

-

Wayne R. Austerman, “The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, CSA,” 96 ↩︎

-

Deposition of George H. Giddings, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Deposition of William A. Wallace, Giddings vs. The United States ↩︎

-

Wayne R. Austerman, “The San Antonio-El Paso Mail, CSA,” 97 ↩︎

-

Anonymous, Special Presidential Pardons for Confederate Soldiers: A Listing of Former Confederate soldiers requesting full pardon from President Andrew Jackson, (Signal Mountain, TN: Mountain Press, 1999), i-iii ↩︎