San Antonio Police, 1874–1885

“From 1874 to 1885 Tom Rife was on the city police force and won the record of a wise and valiant officer”

— “Custodian of the Alamo,” San Antonio Light, February 23, 1887.

Thomas and Francisca Rife moved to San Antonio.

A Justice of the Peace of El Paso County married Thomas Rife and Francisca Eduarda Saenz at Fort Stockton, Texas, on June 13, 1871.1 The groom was 48, and his bride 17-years old.2 It is unknown where or how Francisca Saenz and Tom Rife met, but they likely met in El Paso, Texas. She told a census enumerator in 1900 that she emigrated from Mexico in the year of her marriage; alternatively, she may have met her husband in Mexico.

Tom and Francisca traveled to San Antonio, perhaps to visit and to look for work in 1871, where they visited Mrs. Lizzie Stevens, wife of Deputy Sheriff, Edward Stevens. Later, in an affidavit, Mrs. Stevens swore that she saw Thomas and Francisca’s marriage certificate in 1871 and that it bore the signature of a Justice of the Peace from Fort Stockton.3 Tom and Francisca moved to San Antonio in 1872; their first child was born in April 1873.

In the 1870s, San Antonio was an unusually cosmopolitan town with a mixed population of Anglos, Germans, Slavs, Mexicans, and French.4 Rife’s bilingual family lived in the Mexican part of town, attended Mass at the Mexican church, and associated with Mexican politicians, but Rife and his children were comfortable in and accepted by the Anglo and German communities as well.

For several years after the Civil War San Antonio looked much as it did in 1855, when a traveler observed, “Many houses were roughcast on the outside; some were made of stone, some of adobe. Others were built of tree trunks-some of which were irregular and crooked-set in the ground and bound together at the top with transverse pieces of lumber, outside and inside, tied with thongs of rawhide, the interstices between the tree trunks filled with lime mortar, the roof thatched.” 5 He was describing a construction style locally called “jacal”.6

Between 1866 and about 1877, the San Antonio City government was short of funds. Taxes tied to property values financed City government.7 As other taxes rose during Reconstruction, real estate values and City revenue both fell. For the first ten years after the Civil War, the City struggled financially. The gas works, built in 1859, was idle because there was not enough US currency in circulation to run it.8 Despite this, the City was growing rapidly.9

Rife found work with the City of San Antonio.

In 1874 Rife began a 20-year career as a municipal employee in San Antonio. Perhaps his experience in the election in Fort Stockton redirected his energies toward public service. His earliest contacts when he moved to San Antonio were lawmen such as Ed Stevens, Juan Cardenas,10, and Alejo Perez Jr., who were also politicians.11 Rife is referred to in the City Council minutes of October 3, 1876, as “Policeman Rife.” 12 In a letter to the editor, a disgruntled citizen described Rife as a former “cattle impounder.” 13

In 1879, Alejo Perez was the 2nd Assistant Marshal of San Antonio14 and a well-respected citizen.15 He may have known Rife from the New Mexico Campaign when Perez was a Fourth Corporal in Company B of Baylor’s Command.16 Perez’s mother, Mrs. Juana Navarro Perez Alsbury, and his aunt, Gertrudis Navarro, were in the Alamo when it fell to the Mexican army in 1836.17 Perez was an infant then, but his mother clearly remembered what she lived through. Alejo’s family may have been one source of Rife’s extensive knowledge of the siege of the Alamo.

Rife’s oldest child was born in San Antonio in 1873.

Rife’s first-born son, William Wallace Rife, was born on April 6, 1873. Although Thomas Rife’s father and brother were both named William W.18 the child was also named after Thomas’ former ranger captain and co-worker, William (Big Foot) Wallace. Father Guillet baptized the infant (as “Guillermo”) in San Fernando Church on May 22, 1873. The boy’s godparents were Juan Cardenas and his wife, Josefa Valdez.19

All the Rife children were baptized at San Fernando Church, the Spanish-language parish of San Antonio. All had Spanish given names except for the daughters, Mary Jane and Anna. As adults, the children used the English version of their given names on surviving documents. This family was bilingual, and about half of the children married Anglo partners, and the other half married people with Hispanic surnames. Half of the given names of the grandchildren of Thomas and Francisca Rife can be identified as Hispanic while the other half are clearly of Anglo origin. The Rife family seemed to move easily between two of the three dominant cultures in San Antonio.

When Rife chose to align himself with Ed Stevens and when he chose Juan Cardenas20 as his son’s godfather, he located himself within the minority of Anglo Texans who were not contemptuous of or afraid of the native-born Tejanos or Mexican-Americans. Captain Cardenas was an outspoken advocate for the Mexican community21, and it is unlikely that Rife, who also had strong ties to the Mexican community, would have advocated for or approved of the segregation, expulsion or disenfranchisement of San Antonio’s Mexican-American citizens.

A second child was born in 1874.

The Rife’s second child, Thomas C. Rife Junior, was born on July 16, 1874. Father Neraz22 baptized him as “Tomas” at San Fernando Church on September 13, 1874. The child’s Godparents were Pedro and Rosa Caballos.23

Two daughters followed in 1875 and 1877. Their first daughter, the Rife’s third child, was born on December 26, 1875. She was named Mary Jane, 24 after Rife’s younger sister, Mary Jane Wade. The Rife’s fourth child and second daughter, Francisca Eduarda, was born on May 03, 1877. Father Louis Genolin at San Fernando Cathedral baptized her more than two years later on May 29, 1879, when it was apparent that the baby would not survive. 25 She died of smallpox 26 six days after being baptized and was buried by Father Neraz. 27 This child was the only one of the twelve Rife children to die as an infant. Her Godmother was Dolores Cloud. 28

Rife was appointed as Pound Master of the City’s dogcatchers.

The dogcatchers operated as an office of the police department. By the spring of 1877, the City Council agreed to do something about the “vagrant dog nuisance” 29, and on June 30, newspapers reported that a dog ordinance was to be enforced. Dog owners were to buy a dog tag in order to avoid having the dog caught and impounded. There was also to be “a pound erected and a pound-master appointed, whose duty it shall be to seize and impound all dogs not provided the check or plate.” 30 In the next two months, newspapers aired much criticism of the program. Some writers stated that the effort was a failure. One writer explained it this way, “…any city dog had sense enough to escape being caught. Only pet dogs and country curs would allow the dogcatcher to approach near enough to throw his rope over their heads.” 31 An article in the newspaper reported that even though Rife’s best roper was in jail for disturbing the peace, his department still had a good month. 32

A fifth child was born in 1878.

Anna Rife, the fifth child and the third daughter of Tom and Francisca Rife, was born on June 3, 1878, when her mother already had five children under the age of five. Father Genolin baptized Anna six months after her birth on December 10, 1878, in the San Fernando church. The Godparents were Andres Garza and his wife, Serafina Marquez. 33 He, his wife, and two girls lived at 712 North Frio Street in the same block as Dolores Cloud. 34

Rife served the police department as a jailer.

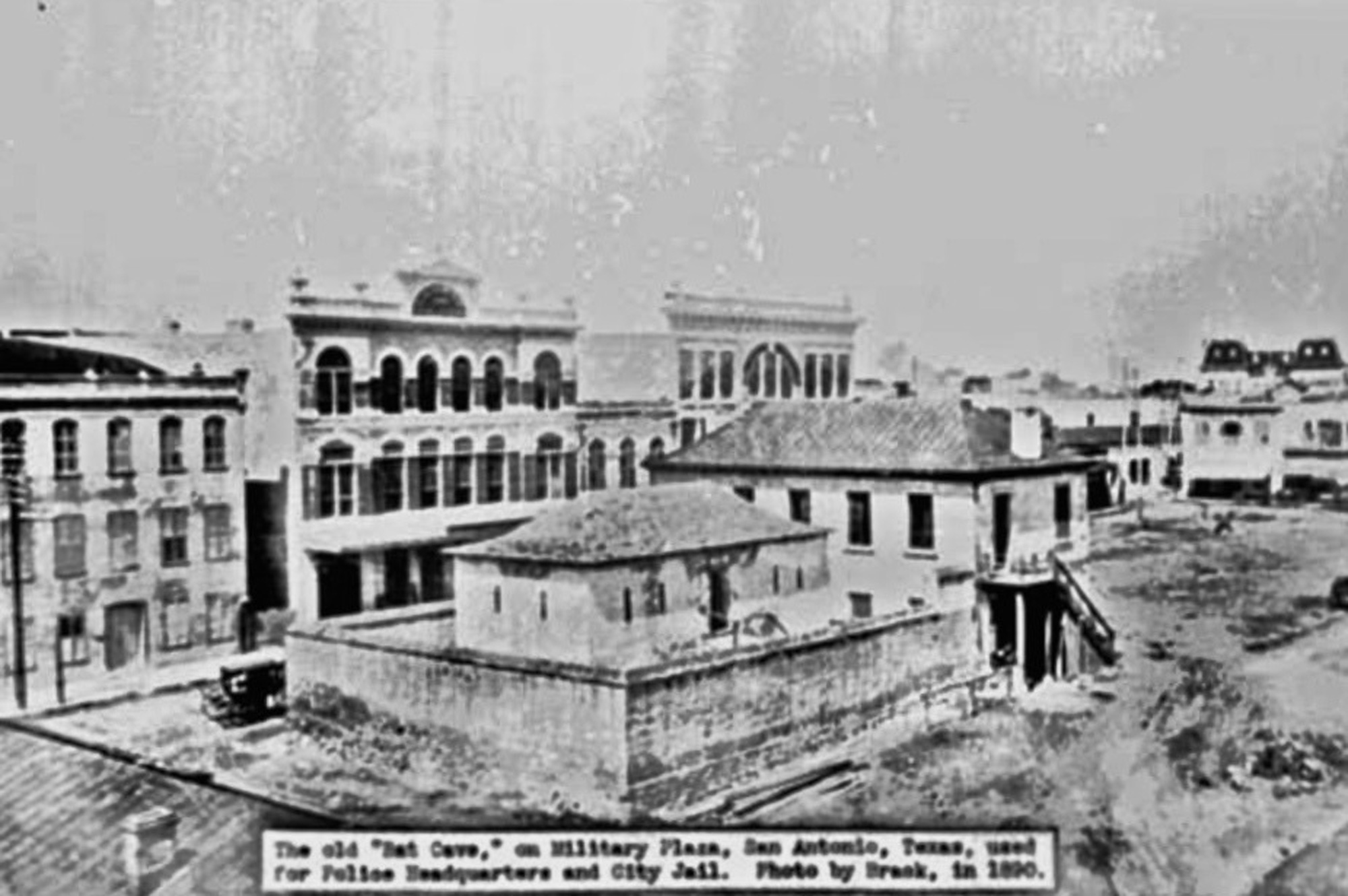

The building known as the Bat Cave on Military Plaza housed the combined city and county jail. Rife’s job title was Vice City Jailer, and he was also the night clerk of the Recorder’s Court. He managed the jail during the night shift. His job was to register persons arrested by policemen working during the night and keep them until their case could be heard by the Recorder’s Court the next morning. Rife worked in this job until March 1, 1879, when Officer Henry Miller resigned, and Rife took his place as a regular policeman. 35

In 1873, the City of San Antonio appointed John Dobbin as the San Antonio City Marshal, and he began to reorganize and modernize the police force. Beginning in 1875, San Antonio police officers were required to wear a badge and standard uniforms and conceal their firearms under their uniform coats. 36 Guards at the City jail, including Rife, wore a similar uniform. By January 1879, Phil Shardein replaced John Dobbin as City Marshal 37 and kept the position throughout most of Rife’s career on the police force.

The sixth child was born in 1879.

Lawrence Wade Rife was the Rife’s sixth child, born on November 19, 1879. Although his birthdate on the baptismal record was written as 1878, the June 1880 census listed him as seven months old, which means that he was born in 1879. He was almost certainly named after Lawrence Thompson Wade, the husband of Rife’s sister, Mary Jane Wade, who lived in Mississippi. Father Genolin baptized the child in San Fernando church as Lorenzo on January 6, 1882. His Godparents were Alejo E. Perez and his wife, Antonia Rodrigues.38

Alejo E. Perez came from an old San Antonio family and worked with Rife on the police force. Like Juan Cardenas, Perez later served as President of the Sociedad Mutualista Mexicana, a Mexican benevolent association formed in 1883. This society had 160 members in 1887-1888 and met every Saturday at the City Recorder’s Office on Military Plaza. Captain Juan Cardenas was godfather to sons of both Rife and Alejo Perez. 39

Thomas Rife worked at the Bat Cave.

Until 1892 the police worked out of the combined City Hall, police station, and City and County jail at the northwest corner of Military Plaza.40 The building dated from 1850 41 and was known as the Bat Cave 42 because of the large number of bats that roosted in the building’s eaves.43 A 15-foot high wall surrounded the two-story stone building. The jail was located on the second floor while the police station and a courtroom occupied the ground floor.

Rife became Grantee of Confederate Scrip.

In April, the Texas Legislature approved a bill giving land to disabled Civil War veterans from Texas. Rife’s certificate 44 was for 1,280 acres of vacant, unreserved, and non-appropriated public land. He was one of 2,068 men who received Confederate Scrip.45 To be eligible, the veteran could not own property valued at more than one thousand dollars.46 Just two months after receiving the grant, Rife signed a notarized bill of sale for his scrip at the price of $80 to a land speculator named Jacob Kuechler of Travis County.47 Most grantees sold their certificates rather than bear the prohibitive costs of surveying and patenting the land. Kuechler, a civil engineer, and surveyor used the scrip to patent 1,120 acres in Zavala County.

In November 1881, Rife was a member of the Bexar County Association of Mexican War Veterans. He was the group’s treasurer in 1887.48 Like most of the Association’s members, Rife was an amateur historian.49 In January 1884, when John (Rip) Ford, a Texas military veteran, and historian, moved to San Antonio from Brownsville, he joined the Alamo Association 50 as well as the Bexar Association of Mexican War Veterans.51 In 1891 he and Rife collaborated on a book about the Mexican War.52

The seventh and eighth children were born.

On February 28, 1881, Morris Wade, the Rife’s seventh child and fourth boy, was born. Morris was named Mauricio after his maternal grandfather. Father Genolin baptized the baby on January 29, 1883, in San Fernando church. 53 Fred, baptized as Federico, was born in June 1882.54 Nothing is known of Fred except that he died at age 28 of Tuberculosis.55

Rife moved his growing family to a different rental house in San Antonio every two or three years. In 1881-1882 the Rife family lived on the east side of Presa Street. 56 In 1883, they lived at 428 North Laredo and in 1885 at 430 North Laredo57 west of San Pedro Creek in the Mexican area of town.

Rife earned a reputation as a valiant police officer.

Rife’s name appeared regularly in crime reports in the city newspapers beginning in 1883. He responded to domestic disputes 58 and arrested drunkards for raising a disturbance or cussing and throwing rocks. 59 Sometimes, he had to disarm violent or angry citizens.60 In March 1884, Rife and his partner arrested two men who were heard conspiring to assassinate San Antonio Police officer Jacob Coy.61 Earlier, Coy had killed Ben Thompson and King Fisher, two men widely known for bloody and desperate acts, including the killing of Jack Harris, the popular owner of the Vaudeville Theater. A gunfight involving some friends of Harris erupted in the theater, killing both men.62

In those days, there were no police wagons, and so it was necessary to walk the arrested person to the jail in the Bat Cave.63 Drunks, often visitors from out of town, occasionally fought the police.64 Police often arrested cowboys for riding through the streets, shooting at dogs65, and disturbing the peace.

Rife stayed with the San Antonio police force until he was permanently suspended on June 5, 1885, having allowed, as one of two jailers on duty, a convicted notorious highwayman named James McDaniel to escape.66 McDaniel and his partner had been sentenced to imprisonment for life. He loosened a stone in the bathroom wall, slipped through, and climbed over the outer wall. Deputy Sheriff Ed Stevens killed McDaniel while he was resisting arrest on June 30. In Rife’s defense, one of the deputies reported, “…the cement can be picked away with fingers.” 67

After Rife became the custodian of the Alamo, he was not expected to perform police work, and his responsibility did not extend outside of the Alamo building. He was not kept on the rolls of the police force after he became the custodian of the Alamo, although he continued to carry his pistol and had the power of arrest.68 Alamo Plaza was a busy place; in 1893, a shed attached to the south wall of the Alamo church housed a police station69, with four mounted officers assigned.70

-

Frances R. Condra, “E. I. Coyle & Trouble at the Alamo”, Our Heritage 34, No. 2, (Winter 1992-1993), 21; Frances R. Pryor, “Tom Rife, An 1890’s Custodian of the Alamo”, STIRPES 35, No. 3, (September 1995), 46; Mexican War Pension Records, Thomas Rife file, Daughters of the Republic of Texas Library, Alamo, San Antonio. ↩︎

-

Mexican War Pension Records, Thomas Rife file, DRT Library. ↩︎

-

Witness’s Affidavits, Widow’s Application, U.S. Department of Veteran’s Affairs, Records of the Bureau of Pensions, Mexican War Pension Applications Files, 1887-1926, RG 15, National Archives and Records Administration ↩︎

-

Colonel Nathaniel Alston Taylor, The Coming Empire or Two Thousand Mile on Horseback (Dallas, Turner Company, 1936), 97-9; Donald E. Everett, San Antonio: The Flavor of it’s Past, 1845-1898, (San Antonio: Trinity University Press, 1975), 3 ↩︎

-

Ophia D. Smith, “A Trip to Texas in 1855,” Southwest Historical Quarterly, July 1955, 36 ↩︎

-

“Fort Clark and the Rio Grande Frontier,” Texas Beyond History;* UT @ Austin College of Liberal Arts, www.texasbeyondhistory.net/forts/clark:accessed Dec 14, 2012 ↩︎

-

W.C. Nunn, Texas Under the Carpetbaggers, (Austin: University of Texas, 1962), 167 ↩︎

-

Charles Ramsdell, San Antonio: A Historical and Pictorial Guide, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1959); James Frontier and Pioneer Recollections, 93 ↩︎

-

Taylor, The Coming Empire or Two Thousand Mile on Horseback, 97-9; Ramsdell, San Antonio, 48 ↩︎

-

Witness’s Affidavits, Widow’s Application, Records of the Bureau of Pensions. ↩︎

-

San Antonio Light, November 8, 1884 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Light, February 23, 1887; San Antonio City Council Minutes, 1870-79, Book D, 255 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Daily Express, August 1, 1877 ↩︎

-

Bill Harvey, Texas Cemeteries: The Resting Places of Famous, Infamous, and Just Plain Interesting Texans, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003), 230 ↩︎

-

Gale Hamilton Shiffrin, Echoes from Women of the Alamo, (San Antonio: AW Press, 1999), 71 ↩︎

-

Martin Hardwick Hall, The Confederate Army in New Mexico, (Austin: Presidial Press, 1978), 313 ↩︎

-

Shiffrin, Echoes from Women of the Alamo, 71 ↩︎

-

Anonymous, Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Mississippi, (Chicago: Goodspeed Brothers Publishing, 1891), 681 ↩︎

-

Baptismal Records, San Fernando, Vol: 7/8, p. 536, entry 3888, Chancery Archives, Archdiocese of San Antonio. ↩︎

-

San Antonio Express, July 14, 1890. ↩︎

-

San Antonio Express, August 16, 1883. ↩︎

-

Mary H. Oglivie, “Neraz, Jean Claude,” Handbook of Texas Online, (www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fne16), accessed March 05, 2011. ↩︎

-

Baptismal Records, San Fernando, Vol: 9, p. 26, entry 189 ↩︎

-

Mary Jane Rife, Certificate of Death, Texas Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics ↩︎

-

Baptismal Records, San Fernando, Vol: 9, p. 155, entry 1414 ↩︎

-

Thomas Rife, United States Tenth Census (1880), T9. San Antonio, Bexar, Texas, 26; (1470) Death Records, 1875-1879, Municipal Archives and Records, San Antonio ↩︎

-

Burial Records, San Fernando, p. 23, Chancery Archives, Archdiocese of San Antonio ↩︎

-

Baptismal Records, San Fernando, Vol. 9: p. 155, entry 1414 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Daily Express, March 20, 1877 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Daily Express, June 30, 1877 ↩︎

-

Letter from J.C. Burrus to Mary Jane Burr, February 15, 1909, original owned by Susan Majewski ↩︎

-

San Antonio Express, October 18, 1936; San Antonio Daily Express, July 17, 1877 ↩︎

-

Baptismal Records, San Fernando, Vol: 9, p. 144, entry 1304 ↩︎

-

Morrison & Fourmy’s General Directory of the City of San Antonio for 1879, 144 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Daily Express, March 1, 1879 ↩︎

-

“History of the San Antonio Police Department, Police Department, City of San Antonio, TX,” (http://www.sanantonio.gov/SAPD/History.aspx) accessed Nov. 14, 2012 ; San Antonio City Council Minutes, 1870-79, Book D, 210 ↩︎

-

“History of the San Antonio Police Department” ↩︎

-

Baptismal Records, San Fernando, Vol: 9, p. 228, entry 2136; Morrison & Fourmy’s General Directory of the City of San Antonio for 1879, 212 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Express, May 23, 1893 ↩︎

-

Charles Merritt Barnes, Combats and Conquests of Immortal Heroes, San Antonio: Guessaz & Ferlet Company, 1910), 245; “History of the San Antonio Police Department”; Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1885, sheet 2, Texas 1877-1922, (http://www.libutexas.edu/maps/sanborn/san_antonio_1885) accessed Nov 12, 2012. ↩︎

-

Ramsdell, San Antonio, 108 ↩︎

-

Robert S. Weddle and Robert H. Thonhoff, Drama & Conflict: the Texas Saga of 1776, (Austin: Madrona Press, Inc., 1976), 103 ↩︎

-

James, Frontier and Pioneer Recollections, 42 ↩︎

-

Thomas C. Rife, Application for Confederate Scrip Voucher 718, Texas General Land Office, Austin, TX; Confederate Scrip, Bexar County, Texas, Certificate 718, GLO ↩︎

-

Thomas L. Miller, “Texas Land Grants to Texas Veterans,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly, July 1965, 63 ↩︎

-

Miller, “Texas Land Grants to Texas Veterans,” 61 ↩︎

-

Nunn, Texas Under the Carpetbaggers, 14; Notarized Bill of Sale for Confederate Scrip, Number 718, Bexar County, Texas, file 40913 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Light, November 1, 1887; Fort Worth Daily Gazette, November 4, 1887 ↩︎

-

Galveston Daily News, July 12, 1889 ↩︎

-

Steven B. Oates, ed. John Salmon Ford, Rip Ford’s Texas, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1963), xliv ↩︎

-

Fort Worth Daily Gazette, November 4, 1887 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Daily Light, August 28, 1891 ↩︎

-

Baptismal Records, San Fernando, Vol: 9, p. 258, entry 2454 ↩︎

-

United States Twelfth Census (1900), San Antonio, Bexar, Texas, Roll 1611 ↩︎

-

Fred Rife, Certificate of Death, Texas State Department of Health-Bureau of Vital Statistics, March 13, 1913 ↩︎

-

Morrison & Fourmy’s General Directory of the City of San Antonio for 1881, 233 ↩︎

-

Morrison & Fourmy’s General Directory of the City of San Antonio for 1885, 265 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Light, August 18, 1883 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Light, September 1,3,6,11, 1883 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Light, October 10, 1883; San Antonio Light, September 8, 1883; San Antonio Light, March 17, 1884 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Light, March 14, 1884 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Light, March 12, 1884 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Light, October 10, 1883 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Light, March 17, 1884 ↩︎

-

Alex Sweet and A.J. Knox, On a Mexican Mustang through Texas from the Gulf to the Rio Grande, (Hartford, Ct: SS Scranton and Co. 1883), 354, 368 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Light, June 8, 1885 ↩︎

-

San Antonio Express, June 6, 1885 ↩︎

-

Condra, “E. I. Coyle & Trouble at the Alamo”, 18; Randy Roberts and James S. Olson, A Line in the Sand: The Alamo in Blood and Memory, (New York, The Free Press, 2001) 202; William Corner, compiler and editor, San Antonio De Bexar: A Guide and History, (1890, repr, San Antonio, TX: Graphics Arts, 1977), 144; Galveston Daily News, May 27, 1887 ↩︎

-

The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, OH), June 25, 1893 ↩︎

-

“History of the San Antonio Police Department” ↩︎